"Lilo and Stitch" is a much deeper movie than you think...

I have never heard this talked about by anyone, but the 2002 animated comedy Lilo and Stitch, produced by Disney, is a subtle yet insightful inversion of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. The film uses Frankenstein overtly as a source of ironic humor, but it also comments upon the themes presented in Shelley's novel. In Frankenstein, we see an artificial life-form scorned by his creator and society at large. His isolation and persecution ultimately cause him to become a true monster, murdering innocent victims inflicting havoc upon society. In Lilo and Stitch, we also see an artificial life form scorned by his creator and society at large, but through a stroke of luck he encounters Lilo, who will provide the familial support that Stitch needs in order to become an integrated and benevolent member of society. Lilo and Stitch and Frankenstein project very similar morals-- Both emphasize nature, empathy, and love as sources of psychological health and social harmony; However, they express these themes through opposite means. Lilo and Stitch is a deliberate inversion of the Frankenstein narrative, turning the tragic into the comedic by providing the archetypal monster with charm, talent, and a loving family.

Disney’s Lilo and Stich is absolutely saturated with Frankenstein parallels, which reveal themselves as early as the first thirty seconds of footage. The film opens with the trial of a scientist, Dr. Jumba, in an intergalactic court room. The scientist, who speaks with an eastern European accent, stands accused of “illegal genetic experimentation,” which he claims is “strictly theoretical.” “Created something?” he responds to the Grand Councilwoman inquiries, “but that would be irresponsible… and unethical….” Already we can see where this is going: Dr. Jumba is our Victor Frankenstein, and his genetic experimentation is not strictly theoretical at all.

“Experiment 626” is brought before the council, prompting the apparent villain, Captain Gantu, to ask incredulously, “what is that monstrosity?” The first label applied to our hero is quite telling, both in terms of the film’s plot and in terms of its association to Frankenstein. Like Victor’s creature, Experiment 626 will inevitably have to cope with ostracism and the label of “monstrosity.” Victor’s creature, however, is monstrous in the eyes of society mostly because of its cadaverous construction. Experiment 626 lacks the oozing wounds and exposed musculature, and he also has the advantage of night-vision, super strength, and hyper-intelligence. He is despised because he doesn’t fit into any pre-existing niche. Not only is he abnormal in form, he is genetically programmed to be an instrument of chaos that “destroys everything he touches.” “He will be irresistibly drawn to large cities, where he will back up sewers, reverse street signs, and steal everyone’s left shoe.” He cannot be allowed to live because he is a liability to the existing social order, which is essentially the same reason that Victor destroys his creation’s female companion in Frankenstein.

“It’s an affront to nature. It must be destroyed,” the Councilwoman declares to Dr. Jumba. “It is the flawed product of a deranged mind,” Jumba agrees, and 626 is sentenced to exile on a desert planet— a setting which is a notable reversal of the Arctic climate that Frankenstein’s creature eventually flees to. However, 626 never reaches the desert planet. Instead, he hijacks a police cruiser and kicks it into hyperspace, keeping his hopes alive for a free and prosperous life. The Councilwoman sends for Dr. Jumba, who is tasked with either killing 626 or bringing it back to the Intergalactic Space Station. As is the case in Frankenstein, the creator will attempt to seek and destroy his creation. The opening sequence closes with these foreboding words from Dr. Jumba: “Please, tell me, on what poor, pitiful planet has my monstrosity been unleashed?”

Cut to Earth, a montage: Hawaii, women dancing in hoolah skirts, and waves crashing on the beach. A girl, Lilo, swims through the ocean surrounded by peaceful ocean critters like dolphins and fish, as soft, spiritual female voices sing in the background. This is a true paradise, and every shot seems to emphasize the natural harmony. The overt femininity is also an inversion of Mary Shelley’s world, in which the structure of the plot renders women powerless to affect anything. The chief narrator of Frankenstein is Captain Robert Walton, who is relating the story to his sister Margaret. We hear Frankenstein's story in his own words, and the creature's story is told through Frankenstein's interpretation, but both stories are filtered through Walton. There are essentially three male narrators, the creators and life-givers of the story, but there are no female voices at all. The social agency of females in Shelley’s fictional world is also severely limited. Lilo and Stitch immediately subverts this male bias by introducing Lilo and her sister Nani as our central human characters.

Lilo arrives late to the dance recital. She’s all wet when she arrives, and the other dancers slip on the wet floor. One of them whines to the teacher that Lilo is weird. A fight ensues and Lilo bites her classmate. After class, Lilo explains to her teacher that every Thursday she takes Fudge the Fish a peanut butter sandwich, and today all she had in the fridge was “TUUUNA!”, which would have been an unforgivable thing to feed to Fudge.

“Lilo, Lilo,” the teacher cries, “Why is this so important?”

“Fudge controls the weather,” she says.

Lilo is characterized from the get-go as motherly, empathetic, and fond of nature, but friendless because of her moodiness and quirks. When she apologizes and asks the other girls if they want to play dolls, they ask her if she has one to play with. She does, she says. “This is Scrum….” a hand-made, stitched-together green doll with buttons for eyes— a far cry from the beige plastic Barbies owned by her friends. Scrum, of course, is also reminiscent of Frankenstein’s creature. He is stitched together like Shelley’s monster, his fabric “skin” is discolored, his eyes abnormal, and he is monstrous compared to the other dolls. When the other girls flee in disgust, Lilo heartbreakingly drops her pal Scrum on the ground and walks away, only to walk back a few moments later, pick him up, and hug him. This action foreshadows Lilo’s personal motto, “Ojana means family, and family means nobody gets left behind or forgotten.” Empathy is also being revealed as a central theme in the movie. Lilo has shown empathy to everyone so far, even fish and inanimate objects, while virtually no one has shown empathy to Lilo or 626.

Lilo walks home, and barricades herself in the house. It is revealed that Lilo and her older sister Nani have been living alone after the sudden death of their parents. Nani is overwhelmed by this responsibility, and has been audited by a massive and intimidating social worker with tattoos on his hands. He arrives at the worst possible moment, witnesses the chaos of their living situation, and offers Nani a grave warning. If she doesn’t prove herself to be a loving and responsible guardian, Lilo will be taken away to live under government care. “We’re a broken family, aren’t we?” Lilo asks her sister. Lilo and Nani have only each other, and the audience is made to understand how devastated they would be if they were separated. Sitting on her own bed, Lilo shows her sister photos of odd-looking people she has seen around town and at the beach. Most of them are overtly abnormal, fat, sunburned, or stragely shaped. They are human examples of a benign monstrousness. “Aren’t they beautiful?” Lilo asks, before reminding her sister of the family motto: Ojana means family, and family means nobody gets left behind or forgotten.

Later that night, Nani eavesdrops on Lilo as she prays beside her bed. Lilo says, “It’s me again. I need someone to be my friend. Some one who won’t run away. Maybe send me an angel!”

Moments later, 626 descends from the sky and crashes into the woods, prompting Lilo to exclaim that God has sent a shooting star and her wish will come true. The fallen star and the angel are indeed one and the same, a curious similarity to the mythical Satan, who is variably referred to as a fallen angel or fallen star. By the same token, it is also reminiscent of the monster’s observation in the end of Frankenstein that “the fallen angel becomes a malignant devil.”

The following day, Nani takes Lilo to the pound to pick out a dog. In the meantime, 626 has been hit by an eighteen-wheeler and tossed into the very same pound, presumed to be dead. Lilo is sent in to pick out a dog just as Dr. Jumba arrives to assassinate his creation. 626, thinking quickly, sucks in four of his limbs and pretends to be a dog. Lilo says hi, and the “dog” says hi back.

Nani and the manager are horrified when they see the dog Lilo has chosen. “What is that thing?” Nani cries.

“A dog I think! it was dead this morning!”

“Well, I like him!” Lilo declares. She convinces Nina and the manager to let her keep him, as the creature meanwhile uses her like a human shield.

“This is low even for you!” says Jumba, Lilo and 626 in his sights. At this point, Lilo’s trust in 626 seems very naive. 626 does not care about Lilo. He only cares about escaping, and he is willing to put Lilo’s life in danger to do so.

Nani asks Lilo what she wants to name her dog, to which she replies “Stitch.” On one hand, the word stitch suggests “mending.” It also suggests “stitches,” such as those used to assemble Victor’s monster from an assortment of parts. “That’s not a real name in…. Iceland,” the manager responds. “But here it’s a good name.” Her random mention of Iceland at this moment also serves to link the name Stitch to Frankenstein, as Iceland is the stated destination of Captain Waldon’s ship. This moment is also thematically pertinent to Frankenstein because Victor’s creature is never given so much as a nickname to identify him as a member of society.

Now the stage is set. Stitch is in danger, and he is jeopardizing Lilo and Nina’s precarious family unit, but there is still hope that he can be tamed and become the angel that Lilo wants him to be. Like Frankenstein’s monster observes the De Lacey’s, Stitch observes Lilo and Nina, learning English and human customs. Lilo informs him that his “badness level is really high for someone his size” and that they’ll “have to work on that.” Dr. Jumba attacks Stitch at Nina’s place of work, and Nina ends up getting fired. The Social Worker tells Nina she needs a new job and she needs to be a “model citizen.” Lilo continues Stitch’s social training, telling him, “Elvis Presley was a model citizen. I’ve compiled a list of his traits for you to practice.” Before long, Stitch is wearing sequined, white jackets and playing electric guitar, but Lilo is in even greater jeopardy of being taken away, and for this reason Nina insists that Stitch be sent away. Stitch says “Ojana,” however, prompting Nina to empathize with him. Frankenstein’s creature received no such sympathy or understanding when he revealed himself to the De Lacey family.

Stitch promptly uses his second chance to start ransacking Lilo’s room, tearing up artwork and pillows. Lilo puts a lei of flowers around his neck and he is instantly pacified, calling to mind the tranquility Frankenstein and his creature both find in natural things. “Happy, inanimate nature,” Victor says, reflecting on his time with Clerval, “had the power of bestowing on me the most delightful sensations. A serene sky and verdant fields filled me with ecstasy. The following day, Nina attempts to get a job as a lifeguard, but loses the job after Stitch is once again attacked by Dr. Jumba. Nina and Lilo bursts into tears, but Nina’s guy friend shows up to support them. At rock bottom, they all go surfing, and the intimacy with nature allows them all to relax and unwind as a group. At one point, the camera faces up at Lilo as he looks into water. As an audience, we presume he is looking at his reflection for the first time, but he is not alarmed or ashamed of his appearance like the creature of Frankenstein. The camera angle changes. He is really looking at Lilo and her sister swimming in the clear water beneath the surf board, suggesting that his identity is being shaped by his personal bonds more so than his outward appearance.

Dr. Jumba shows up again and drags Lilo and Stitch underwater. Nina’s friend rescues the two just as the social worker arrives on the beach. He tells Nina that things must change drastically, immediately, or Lilo will be gone in twenty-four hours. He says, “You need to think about what’s best for Lilo, even if it removes you from the picture,” and we as an audience are aware of his flawed perspective, that Nina, Stich, and family are what’s really best for Lilo.

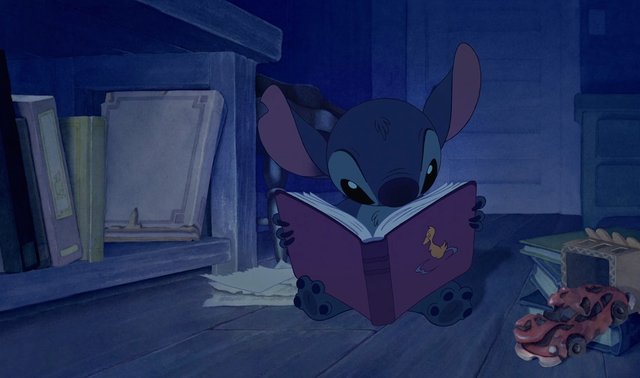

That night Lilo shows Stitch her only remaining photo of her parents, the four family members smiling happily on the beach. Stitch is visibly saddened when Lilo tells him that they were killed in a car crash. Later in the night, a sleepless Stitch digs through Lilo’s bookcase. He humorously passes over Oyster Farming: Is It For You? and Road Maps of Iowa before getting emotionally floored by The Ugly Duckling, just as Frankenstein’s creature is floored by reading Paradise Lost. Stitch wakes up Lilo, and she explains the story to him. The ugly duckling is “sad because he’s all alone and nobody wants him. But on this page his family hears him crying and they find him. Then the ugly duckling is happy, because he knows where he belongs.” The story of the ugly duckling, of course, is opposite to that of Satan in Paradise Lost. Both are all alone and estranged from family, but Satan is cursed by his own actions to remain estranged from God, his father. The ugly duckling, meanwhile, waits with heart-tugging patience for his mother and his siblings, and they eventually return to him, happy to see him. The mirroring between these two stories is a microcosm for the mirroring between Lilo and Stitch and Frankenstein.

After Lilo falls asleep, Stitch sneaks out of the window. No longer fleeing for selfish reasons, he flees selflessly in order to preserve the bond between Nina and Lilo. He finds himself alone in the woods with nothing but his copy of The Ugly Duckling, which he sits down to read. Staring down at the page, he reads aloud, “I’m lost! I’m lost…” uniting his character with the duck in dramatic fashion. Dr. Jumba appears from the bushes, gun aimed. He takes Stitch captive and informs him, “You’re built to destroy. You can never belong.” This low-ball estimate of Stitch’s social capacity is comparable to Victor’s utter disdain and fear for his own creation. Stitch, however, has found family elsewhere, and the love he has learned from his family is the central cause of his ultimate salvation.

Fed up with Dr. Jumba’s bumbling attempts to capture “626,” the Grand Councilwoman sends Captain Gantu to Earth. Lilo’s home is obliterated by aliens in a shoot-out, as Nani meanwhile is out finding a new job. Nani, excited about her new job, gets home just in time to see the burning rubble of her house, and Lilo being put into the social worker’s car before escaping and fleeing into the woods. Lilo and Stitch run into each other, and Lilo realizes that Stitch is no dog at all, but an alien. “You’re one of them?” she says incredulously. “Get out of here Stitch.” In this moment Lilo’s empathy fails, even though she has been the most consistently empathetic character throughout the movie. Seemingly, all hope is lost. Stitch’s capture is imminent, Lilo is set to be taken away, and at the depths of her sadness she lashes out Stitch, forgetting that Ojana means family and that Stitch is a part of the family now— not just an alien.

Captain Gantu arrives and captures Lilo. All the pressure now falls to our hero, Stitch. Stitch has just been told to “get out of here,” which has been his goal from the get-go, but he sees Nani crying and he knows that he cannot leave the family in such disrepair, particularly when it is mostly his fault. He solicits the help of the social worker, Nina, and Dr. Jumba, and flies a spaceship to get Lilo back. With everyone now on the same team, they are super effective. Lilo is rescued, Stitch inevitably invokes “Ojana,” and the Grand Councilwoman arrives to escort him back to the Intergalactic Space Station. She is emotionally moved by his development and the bonds he has formed, however, and she agrees to allow Stitch to live in “exile” on Earth, much to the joy of Lilo and her sister. The movie closes with a montage of photos, all family activities featuring Lilo, Nina, and Stitch, the social worker and Dr. Jumba joining in on the fun and eating birthday cake.

By the end of the film, ubiquitous social harmony is achieved, Lilo’s family is saved, her “cosmic family” has grown exponentially, and all is well in paradise. Stitch is now a fully integrated member of society and the good angel that Lilo wished for. “Nurture” has defeated “Nature,” in the sense that we are all free to craft our own identities, and a loving family can tame even the most wild beast. Even Stitch, who was literally programmed to be chaotic, destructive, and untamable, has become a functional and well-liked member of society. All of the supposed villains of the story— Jumba, the Grand Councilwoman, Captain Gandu, the social worker— all of them become a big, galactic family in the ending, demonstrating that no one is purely evil, and everyone deserves a second chance. This ending, of course, is a complete reversal of Frankenstein, an ending which also, according to Anne Mellor, grounds moral virtue in the preservation of familial bonds. Frankenstein’s monster approaches his death on the barren arctic ice, cut off from family, nature, and society.

Like Stitch, Shelley’s creature is also characterized as empathetic— he regrets each of his murders horribly— but the hatred of his peers engenders self-hatred, creating a feed-back loop of rage, resentment, and estrangement from society. Frankenstein’s creature is made a monster not by his physical appearance or the circumstances of his creation, but instead by his alienation and the spitefulness of a patriarchal society. Without the support of familial bonds and a nurturing environment, Frankenstein’s creation inevitably becomes the murderous beast that he is known to be. Lilo and Stitch operates using this same model, but it inverts it, showing us what could have happened if Frankenstein’s creature had received the love and acceptance it deserved.

Cover Photo: Image Source

Amazing post! Another example could be beauty and the beast.

Lilo y stitch me encanta, cada vez que puedo la veo!

Yes, really behind this movie there is a very special message. I loved it, I felt it even in my skin.

long time no see

el amor cambia a muchas personalidades, jejeje excelente post gracias por compartirl

we must do ordinary things with extraordinary love and changes will be seen, thanks for sharing.

"Lilo and Stitch" muy buena pelicula animada para disfrutarla en familia en esoecial con los más pequeños de la casa @youdontsay

Please upvote: https://steemit.com/free/@bible.com/4qcr2i

To listen to the audio version of this article click on the play image.

Brought to you by @tts. If you find it useful please consider upvoting this reply.