Barter and the Need for Human Empathy

Barter and the Need for Human Empathy

Introduction

Before the invention of money and the development of widespread numeracy, human societies relied on barter as their primary method of trade. Barter is not merely a simplistic exchange of goods and services; it was rooted in human empathy, mutual understanding, and the shared recognition of needs.

In the absence of standardised value and common currency, barter was a negotiation guided by emotional intelligence and social bonds. This post will explore how empathy was central to barter in early human societies, using Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs to frame examples of empathetic exchanges. The key argument is that barter, before 600 BCE, was primarily driven by empathy and human connection, which were necessary for satisfying both basic and higher-level human needs.

The Structure of Barter and Empathy

Barter, the exchange of goods and services without money, was the economic lifeblood of early societies. Each transaction was not only a practical matter but a personal interaction, as traders had to empathise with each other’s needs. Since there was no currency to quantify value, each trade was subjectively negotiated, and this process was inherently driven by empathy—the ability to understand the other party’s perspective and desires. As we examine the specific examples below, it becomes clear that barter and empathy were intertwined, forming the foundation of economic and social relationships.

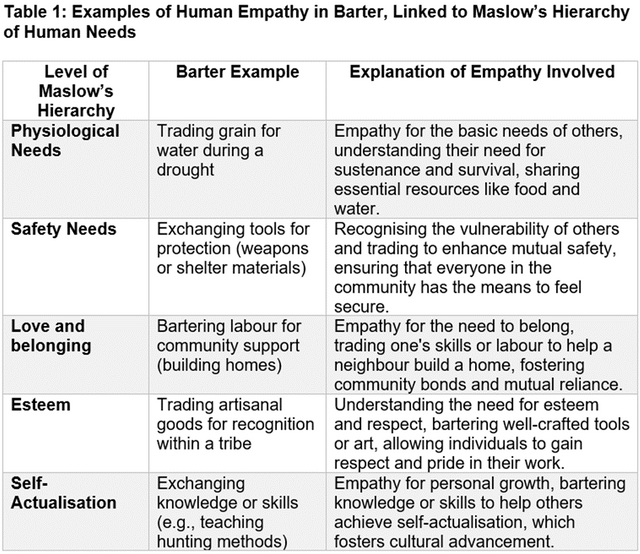

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Linking Empathy with Human Exchange

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs provides a useful framework to analyse barter systems. Maslow identified five levels of needs: Physiological Needs, Safety Needs, Love and Belonging, Esteem, and Self-Actualisation. The examples below demonstrate how barter exchanges in early societies met these needs through empathy-driven interactions.

Examples of Barter and Human Empathy

1. Bartering Grain for Water: Physiological Needs

In early agrarian societies, where natural resources were critical for survival, physiological needs (such as food and water) were often met through barter. During periods of drought, those who had access to a well or river would barter water with those who had a surplus of grain. The empathy involved in this exchange is clear: the individual with water would recognise the desperation of the person whose crops had failed and understand that their family needed food to survive. Conversely, the person with grain would empathise with the thirst and vulnerability of the water-bearer.

For instance, a farmer who had abundant wheat after a successful harvest might trade sacks of grain to a neighbour whose well had not dried up. The farmer understood that without water, the crops would not matter, and the neighbour, in turn, knew that without food, their water supply was of little use. Both parties recognised each other's needs and made an exchange based on this mutual empathy. Here, the exchange wasn’t just transactional but grounded in understanding and fulfilling the other’s basic survival needs, in line with Maslow’s physiological level.

2. Trading Tools for Protection: Safety Needs

The need for safety protection from danger, harsh weather, and conflict was a pressing concern in early human societies. Bartering tools, such as farming implements or weapons, to build a secure shelter or defend oneself, was a common practice. For instance, a blacksmith might trade knives or spears in exchange for materials to build a stronger house or a food supply. In these exchanges, empathy was essential because both parties understood that their security and survival were interconnected.

In one example, a villager who specialised in making strong wooden doors might trade these items to a hunter in exchange for a share of the hunter’s game. The villager recognised the hunter’s need for protection from wild animals while the hunter empathised with the villager’s need for sustenance. Both parties valued safety one through physical protection, the other through food security and through empathetic understanding, they supported each other’s wellbeing.

3. Labour for Community Support: Love and Belonging

Communities in early societies thrived not just on individual efforts but on collective support. The need for belonging a sense of being part of a group was fulfilled through communal work, which was often facilitated by barter. For example, individuals might offer their labour in exchange for food, shelter, or other forms of support, particularly when building homes or gathering harvests. The empathy in these exchanges lay in the understanding that helping one’s neighbour would result in reciprocal help in the future.

Imagine a scenario where a man trades his labour to help build a neighbour’s house. In return, the neighbour agrees to help the man harvest his crops at the end of the season. The understanding here is not simply a transactional one; both individuals recognise the importance of community ties and the need to support each other. The empathy exchanged through this barter lies in the mutual recognition of vulnerability: the builder needs a secure home, and the farmer needs help with a task too large to manage alone. These exchanges strengthened the sense of belonging within the community.

4. Artisanal Goods for Recognition: Esteem

Barter was also a way to gain esteem and recognition in early societies. Artisans, who produced high-quality or specialised goods, often traded these items in exchange for food, tools, or other materials, but these transactions also fulfilled their need for recognition and respect. For example, a potter might trade intricately designed pottery to a chieftain or a tribe’s leader in exchange for protection or livestock.

In such a transaction, the potter would understand that the leader valued prestige and the display of fine goods, while the leader empathised with the potter’s desire for social recognition.

The empathy exchanged in these deals wasn’t just about meeting practical needs but also about acknowledging the other’s emotional need for respect and validation. The potter would feel a sense of pride, knowing that their work was seen and appreciated by important figures in the community, fulfilling the esteem level of Maslow’s hierarchy.

5. Knowledge for Personal Growth: Self-Actualisation

At the highest level of Maslow’s hierarchy is the need for self-actualisation, which involves realising one’s full potential. Even in early societies, barter wasn’t restricted to tangible goods. Knowledge and skills were often traded as well. For example, a skilled hunter might teach a young villager how to track and capture game, in exchange for knowledge about medicinal plants or farming techniques.

The empathy involved in these exchanges lay in the recognition that both parties were striving to become more skilled, knowledgeable, and capable. The hunter understood that the villager wanted to grow as a provider, while the villager recognised the hunter’s need for wisdom about agriculture. By sharing knowledge, both individuals moved closer to self-actualisation, enriching not only themselves but also the community as a whole. These exchanges were based on the understanding that personal growth benefits everyone, linking the need for empathy to cultural and individual advancement.

The Role of Empathy in Successful Barter

For barter to function effectively, the exchange of empathy had to be pure. In a world without standardised currency, each transaction depended on mutual trust and the understanding that both parties were meeting essential human needs.

If empathy were absent or insincere, the system would collapse into exploitation, and the social bonds upon which barter was built would disintegrate.

Barter thrived on the idea that everyone’s needs were valid and that through trade, both parties could be made better off. This required an emotional connection and a sense of fairness that transcended the immediate transaction. Empathy ensured that trade was not simply about goods but about relationships, reinforcing the idea that economic interactions were deeply personal in early human societies.

Summary

Barter, before the widespread use of money and numeracy, was a system of exchange built on human empathy. Each trade required an understanding of the other party’s needs, desires, and vulnerabilities, fulfilling both practical and emotional requirements. Through the framework of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs, we see how barter met the basic physiological needs for food and water, the safety needs for protection, and the higher needs for belonging, esteem, and self-actualisation. In early societies, barter was not just an economic practice but a human one, rooted in the empathy that ensured fairness, trust, and social cohesion.

It's interesting how Bitcoin is able to better exchange and reinforce this empathy.

Sources:

• Glyn Davies, A History of Money: From Ancient Times to the Present Day, University of Wales Press, 2002.

• David Graeber, Debt: The First 5,000 Years, Melville House, 2011.

• Abraham Maslow, A Theory of Human Motivation, Psychological Review, 1943.

• Joel Kaye, A History of Balance, 1250-1375: The Emergence of a New Model of Equilibrium and Its Impact on Thought, Cambridge University Press, 2014.

By Joe Bloggs

#Nostr pub key is: npub1yvlppcwga8k2qsvrh6rtd5cjv6hlmsm52uqsgw38yj36r4zu8wuqulu2dc

Bitcoin Address: 1DEEP7H4qrX7uCpqrx3sdkzGHeDV4L7fWT

Lightning Address: [email protected]