Amazing Animals #23 The Leatherback Sea Turtle

Sea Turtles are truly amazing creatures, they are a group of marine Reptiles that are thought to have emerged around 110 million years ago with certain species remaining relatively unchanged from their early ancestors, the largest descendant alive today is the Leatherback Sea Turtle.

These Turtles share very little in common with other species alive today, they have some completely unique traits from both Sea turtles and Reptiles alike, their shell is soft and has a rubber-like texture, they have a wide, almost global geographic range and they can survive and thrive in cold climates that would normally render cold-blooded Reptiles paralysed, with these oddities in mind I believe they are more than interesting enough to cover in this series!

Description and Distribution

The Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) is the sole surviving species within the family group Dermochelyidae which formerly contained 8 species, the earliest of which diverged from other Turtles roughly 84 million years ago towards the end of the Cretaceous period.

They are the largest species of Sea Turtle on the planet and can grow to lengths of up to 2.1 metres, they can also weigh up to 700 Kg’s making them the fourth heaviest Reptile alive today with only three species of Crocodile ahead of them, the average Leatherback turtle grows to approximately 1.5 metres and weighs between 340-400 Kg’s.

They are unique amongst species of Chelonians (species within the order Testudines including Terrapins, Turtles and Tortoises) in that they do not possess a hard-outer shell, instead their carapace consists of thousands of tiny Osteoderms that are covered by a relatively thin but tough and rubbery layer of skin, from the outside their carapace appears leathery which is where their name derives from.

The general body shape of the Leatherback Sea turtle resembles a teardrop, when viewed from above this is easy to spot at the animals body tapers to a point towards the rear end, a distinctive feature of their soft carapace is the presence of 5 distinct longitudinal ridges that run the length of its body, when partnered with their teardrop shape this gives the Leatherback a superior hydrodynamic body design than other sea turtles resulting in increased drag when descending and increased lift when ascending, their hydrodynamic design enables them to claim the title of the fastest Reptile in the Sea and they are capable of reaching speeds of up to 35 km/hour.

The Leatherbacks Dorsal surface is mainly dark grey or black in colouration though sporadic white blotches can exist across the body, in contrast, their underside is much lighter in colour and often exhibits a hue of pinks, whites and greys, this supplies the Leatherback with a mechanism known as countershading, when viewed from above their dark Dorsal surface blends in with the abyssal backdrop, when viewed from below their lighter colouration is more difficult to distinguish from the light penetrating from above.

Unsurprisingly they have the largest front flippers of any Sea Turtle both in average length and in proportion to their overall body size, larger than average individuals have been observed to have Flippers exceeding 2 metres in length, furthermore their flippers are devoid of any claw formations and are used solely for propelling the Turtle through the water.

The mouth of the Leatherback is devoid of teeth, instead they have a beak-like structure that has a pointed Tomium, unless the Leatherback was capable of snapping its prey efficiently it would likely often lose its meal if it didn’t die instantly, luckily the Leatherbacks throat is lined with thousands of rear facing spines known as papillae that not only aid in swallowing food but also prevent prey from escaping after they’ve been caught, these spines continue all the way down the oesophagus and end as it meets the stomach, before entering the stomach the Leatherback is able to expel water from the oesophagus without losing its prey.

The Leatherback is unique amongst not only Sea Turtles, but also amongst all Reptilian species in that they are capable of actively functioning in temperatures near 0°C, impressively they are able to maintain their body temperature of roughly 26°C throughout a wide and varied climatic range, this is achieved through a complex bundle of arteries and veins in their limbs and a process known as counter-current exchange whereby warm blood travelling through the arteries from the core radiates heat into the veins returning back in to the body.

Their limbs are consistently warmer than their core body temperature which allows the muscles within the limbs to work efficiently even when surrounded with low temperature water, as Leatherbacks are nearly always in motion the movement of their flippers transfers small amounts of heat to the more insulated core of their body, the end result is very little heat loss from the circulatory system and providing the Leatherback increases activity in cooler waters its temperature will remain stable, this is an important adaptation as it allows the Leatherback to hunt effectively in cooler waters, but also prevents them from overheating in warmer waters or when venturing on land (females only).

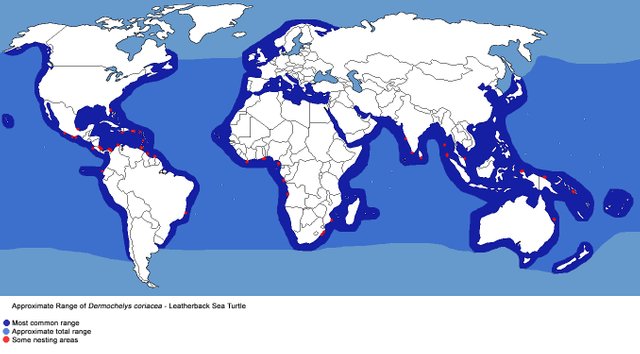

This trait inevitably means that Leatherbacks have the largest range of all Sea Turtles and can be observed in a number of tropical, subtropical and boreal waters, their range is truly global, and populations reside within the Atlantic, Pacific, South Chinese and Indian oceans and individuals may be cited as far south as the southern tip of South Africa, or as far north as coastal Alaska.

Diet and Behaviour

The diet of the Leatherback Sea Turtle consists entirely of soft-bodied organisms, their primary food source is the Jellyfish, but examination of deceased Leatherbacks has shown them to also feed on an array of Cephalopods such as varying species of Squid, Cuttlefish and Octopus.

Leatherbacks are opportunistic feeders and will eat throughout the day should the opportunities arise, as their diet consists primarily of Jellyfish this results in Leatherbacks displaying two different hunting techniques during a 24-hour period.

During the night time the Leatherback can feast on Jellyfish close to the waters surface (0-200 metre depths) as Jellyfish tend to rise through the water column to spawn/feed once darkness has ensued, the Leatherbacks acute sense of smell under water allows them to locate their slow-moving prey in the often-pitch-black darkness of the Ocean at night.

During the day Jellyfish are far less frequent near the water’s surface which obviously presents the Leatherback with a small problem, their method of thermoregulation requires metabolically generated heat as opposed to heat transfer from their environment as observed in most Reptilian species, this led researchers to previously believe that they were reliant on their high resting metabolism to maintain a stable temperature.

However recent data has shown that Leatherbacks may spend as little as 0.1% (1.5 minutes) of their day resting, instead their high activity rate partnered with their previously mentioned form of heat exchange from their limbs to their core enables them to survive in a wide range of climates, this activity inevitably equates to an increase in work done which means they must feed frequently to maintain optimal body function.

With all of this in mind, instead of waiting for the Jellyfish to come to them they instead opt to go to the Jellyfish themselves, they are one of the deepest-diving Mammals on the planet and are capable of diving to depths of up to 1200 metres, only Sperm Whales and Beaked Whales are known to dive deeper.

Testament to their incredible thermodynamic design they can actively hunt in the abyssal depths where sub-surface temperatures can often fall between 0 and 5°C, a typical dive lasts between 5 and 8 minutes though tagged specimens have been observed to infrequently dive for as long as 70 minutes on a single breath.

Sadly for the Leatherback Sea Turtle their main prey, the Jellyfish, closely resembles a not so nutritious food source in the form of plastic bags, it is speculated that a third of all mature adults have ingested plastic and this has been attributed to the rapid decline of certain populations over the past century with 4 of their 7 categorised populations being listed as critically endangered by the IUCN red-list, failure to address these issues will likely see a boom within Jellyfish populations which may cause a shift of potentially detrimental changes to the wider ecosystem.

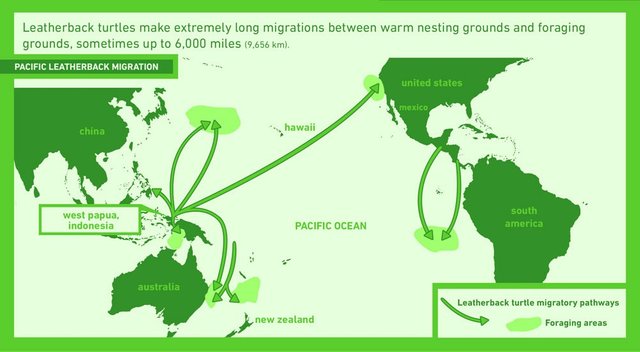

The high activity of Leatherback Sea Turtles also results in them having one of the most extensive migratory feeding routes of any animal where they may cover distances of over 12000 miles on a single journey, this makes them one of the most highly adaptive creatures on the planet regarding their ability to survive throughout a range of different climates.

Aside from feeding behaviours the only other well studied behaviours relate to reproduction, depending on the sex of the Leatherback in question reproductive behaviour varies extensively.

Firstly, males are strictly aquatic creatures, once they’ve entered the Ocean after hatching they will never again migrate to the land from whence they came, in contrast the female will make her journey on to land once every two to three years.

Female Leatherbacks initiate the reproductive cycle by exuding a pheromone which can be detected by males within a small geographic area (generally less than 1 square kilometre), once the male has been alerted he will begin to court the female, to do this he will display a variety of head and body movements which will progressively lead to nuzzling and gentle biting of the female to gauge her receptiveness, should she accept him they will proceed to copulate.

Fertilisation of the female’s eggs occurs internally, and she will display polygamous behaviour, wilfully mating with a variety of males during Oestrus, this inevitably leads to the males having nothing to do with the females after they’ve copulated and very little in the way of conflict between competing males has been observed, mating with a variety of males is not thought to supply the resultant offspring with any advantages.

Generally speaking it is thought that males are able to mate annually (possibly multiple times) whereas females will only be fertile every two to three years, we will now explore the life of the female Leatherback from the beginning.

The life of a Female Leatherback

The life of the Leatherback begins the same for males and females, they hatch from their eggs using a specialised tooth called a Carnucle to break the shell, their journey begins in complete darkness after an incubation period of roughly 60 days, a hatchling triggers other to follow suit and up to 100 baby turtles can hatch from a single nest.

The hatchlings then dig in unison to make the 50-centimetre journey to the surface, once near the surface they will scope their surroundings and will often wait until dusk/twilight until they emerge completely, emerging during daylight poses a larger risk of dehydration, overheating and predation.

Like all other Sea Turtles the hatchlings are instinctively attracted to the brightest area of their surroundings, in a natural sense this will always be either the sun or moon over the Ocean horizon which will lead them to the water, but in recent times artificial lighting such as that seen from Hotels, Bars and Housing is causing confusion amongst hatchlings, instead of heading to the water they are instead heading in land where they inevitably never reach the water and subsequently overheat, get run over by vehicles or get stuck resulting in starvation.

The plight of hatchlings has gained mainstream attention in recent years and various organisations(saddening footage of the modern struggles presented to Sea Turtles) now work to help the hatchlings reach the Ocean, however it is important that the hatchlings are made to enter the water on their own as they must be familiar with their surroundings.

Once in the water the hatchlings life does not become any easier, it has been theorised that only 1-5% of the offspring that make it to the Ocean survive to sexual maturity, this is mainly due to the large number of predators that pose a threat to juvenile Leatherbacks, Cephalopods, coastal Sharks and large fish all pose a serious danger and it seems that surviving to adulthood is more based around luck than anything else.

It is thought that for the first few years of a female Leatherbacks life she will mainly inhabit coastal waters, this is not a concrete theory as very little study has been conducted in to the behavioural patterns of Juvenile Leatherbacks largely due to their woefully low survival rates and difficulty to track, the juvenile years of Leatherbacks are frequently reffered to as "the lost years" because of this, recent theories suggest that they may opt to travel with flotsam debris in open waters as this offers a form of protection from coastal predators whilst still presenting feeding opportunities.

Once matured the female will live a migratory existence, the average foraging range of a female Leatherback is speculated to span a distance of around 3000 kilometres, though on rare occasions this can be as far as 20000 kilometres, this was discovered when a tagged specimen was documented travelling from Indonesia to the west coast of the United states, the migration took place of a time period of 647 days.

When the female reaches sexual maturity at an age of between 15-25 years, she will instinctively begin her migration to a breeding ground, unlike most animals that migrate to breeding grounds based on climatic triggers female Leatherbacks return specifically to the area (or close to it) they hatched from.

It is thought that upon hatching and travelling to the Ocean, the magnetic field signatures of their location is imprinted in to their brain, using the memory of the magnetic field signatures she is then able to make her journey back to the place of her birth.

This is an important adaptation and quite a smart one when you analyse it, a viable nesting site will always consist of a relatively low-angled gradient beachfront made up of a fine sand substrate, if she were to lay her eggs on rocky surfaces the eggs would most likely be damaged and may not be incubated correctly, the only place she is aware of that is a viable location is her birthplace therefore it makes sense to return to it.

Tagged females have been observed travelling distances of up to 5000 kilometres to return to their place of birth to nest, their instinctive memory and ability to detect magnetic signatures is nothing short of remarkable, though changes in the Earths magnetic field can cause the females to be attracted to areas away from their birthplace, this was proven in a study between 1993 and 2011, it states:

A look at the data, from 1993 to 2011, confirmed this idea. At certain times in some places, Earth's magnetic field shifted so that magnetic signals from nearby beaches moved closer together. During these times, turtle nests densely covered these areas, they found.

Similarly, there were fewer turtle nests, and the nests were farther apart, in places where magnetic signatures diverged, just as the researchers predicted.

"Our results provide the strongest evidence to date that sea turtles find their nesting areas at least in part by navigating to unique magnetic signatures along the coast,"

Further research is still required to ascertain exactly how the female Sea Turtles detect the geomagnetic field of the Earth, though it can be seen from the varying nesting cycles in relation to fluctuations in the magnetic field that their ability to detect magnetic signatures plays a vital role in their reproductive lifecycle.

Once the females have copulated and are ready to lay their eggs they will make their way to the beachfront, as the night sets in they will begin their journey up the beachfront, using their powerful flippers they pull themselves across the sand, this is an exhaustive task as she will likely weigh several hundred kilograms and her body is hardly designed for movement outside of a buoyant environment, once she has located a suitable spot she will begin to dig her nest in the sand using her rear flippers, the nest is generally 50-75 centimetres in depth (the variance occurs as larger individuals will dig deeper nests) and after the eggs have been laid she will proceed to cover them with sand.

This entire process regularly takes the duration of the night and she will often be close to exhaustion before re-entering the water, despite this arduous task of nesting, female Leatherbacks may return to the beach every 8-10 days to create a new nest and they may do this up to 10 times during a single breeding season, during the breeding season they stay close to the shore and feed in waters known as “internesting habitats”, the entire 4 month breeding season takes such an exhaustive toll on the females body that she will not be able to reproduce for at least another two years.

The sex of her offspring will be dictated by the temperature surrounding the eggs with warmer temperatures leading to a majority clutch of females, and a cooler nest resulting in a majority clutch of males, the depth of nests obviously has a large impact on the surrounding temperature and varied depths across nesting sites are required to ensure that the distribution of males and females is in a viable equilibrium.

Once her nests have been successfully created the cycle will repeat itself as it has done flawlessly for the previous 80 million years or so, whether this amazing animal continues to exist as it is has done over such a long period of time is no longer within their own hands (or flippers) and I am a firm believer that if you make a mistake it you who should fix it, their future survival, as well as the survival of all nesting Sea Turtles is sadly in our hands.

Content Sources

- Life Cycle of Leatherbacks

- Sea Turtles and Magnetic Fields

- Sea Turtle Metabolism

- IUCN

- Leatherback Sea Turtle Factfile

More Amazing Animals

If you Enjoyed this article feel free to check out some of my previous editions of Amazing animals.

- The Fruit Bats

- The African Elephant

- The African Lion

- The Arctic Fox

- The Peregrine Falcon

- The Komodo Dragon

- The Great White Shark

- The Hyena

Being A SteemStem Member

I love sea turtles! How do you think that climate change will affect sea turtle offspring because their sex is temperature dependent?

I think that climate change will likely have a detrimental impact on the species as a whole, not from a skewed ratio of males/females but from reduced viable nesting sites, with their nesting sites consisting of low-incline beachfronts they are likely to be destroyed should sea levels rise as anticipated, areas that aren't affected by rising tides may also be exposed to periods of drought as temperatures increase, precipitation is vital to keeping the nest cool.

If the changes happened slowly and their global population was healthy I have no doubt that they could adapt to a changing environment, they've survived wild temperature swings in the past and even thrived during a time where global temperatures were 10-15C hotter than today.

I fear that as their populations decline due to factors such as fishing by-catch, pollution, high infant mortality and illegal poaching a rapid climatic change would all but embed the final nail in the coffin and a possibly skewed sex ratio would likely pose a major threat to already critically endangered populations.

That's quite a large turtle there,just took a second look at those scary maws , yeah, just confirmed am brave for the sight :) , amazing indeed. We can only try as much as possible to save their numbers, it's nice the work put into saving them by individuals, applauding.

ermagherd, that they have such papillae is ... disturbing, lol

I feel sorry for their food now. :D

I don't know about the physics of it, but I would have thought that a creature that needs to dive that deeply would need a much larger body mass to withstand the water pressure - like the whales have. Amazing stuff.

Thanks for continuing to share such insights, it is appreciated. :)

Great post! Turtles are great <3 Thanks for posting!

That picture of the turtle next to Attenborough is so amazing - these turtles are huge! But of course human plastic waste in particular is especially damaging to them...

Your posts are awesome but every time I read them I have a twinge of sadness - human pollution is so bad! Anyway, if you have the time and/or interest, writeups on organizations trying to save these amazing animals in various ways (you already mentioned the David Sheldrik, that was awesome, then there's the WWF, IAPF, NRDC, etc etc) would probably be great too - then we'd know who to support as well!

I'm glad you're enjoying the series, it is sad but near enough every animal worth writing about has been impacted negatively by Humans in one way or another.

I did used to have a weekly segment on animal charities, though with all of my other commitments at the moment I haven't got the time to bring it back just yet, until then I'll continue to name drop and mention charities wherever I can.