The Myth That Became Art: How Salvador Dalí Sold His Soul for Money and Signed It on Canvas

Salvador and the Dead Mother: How to Become a Genius Through Psychosis

Salvador Dalí, that peculiar man with a mustache seemingly defying the paradox of time, wasn’t born on a day but in a moment when he realized that mathematics and psychology weren’t for him. From the very beginning, his life unraveled into a shocking spectacle — his mother, whose absence felt like the world might collapse, died when he was just 16. Surprisingly, this wasn’t a tragedy but a monumental failure of reality that Dalí, like a seasoned actor, decided to play to the fullest.

He coped with his mother’s death as only a genius could — not merely by surviving but by insisting she hadn’t died at all, just stepped away temporarily. He even continued to sleep with her portrait. No joke. He talked to it, prayed to it, and treated it as his personal saint. Being the master of surrealism, he had no intention of surrendering to reality. Why leave this world when you can make it work for you?

But what happens when you’re stuck in childhood? You become someone who can’t live without their mother and tries to recreate her image, over and over, breathing her spirit into every painting and gesture. Dalí transformed his grief into a new art form, embedding his mother’s soul into his canvases. Her death wasn’t just trauma — it was a new genre of art he created himself.

This wasn’t merely art; it was a psychological trick — a way to enclose her essence in every work. His paintings became a shrine to her spirit, where the absurd was interwoven with her image.

And then, there’s the moment you realize you’re just a lost soul trying to save yourself through images and psychoanalysis, turning tragedy into a performance. Mystical, isn’t it? Dalí mastered mystification: his life became a show, his tragedy a stage, and the world an audience.

Oh, and yes, he did attempt suicide. He drank poison — cleaning fluid, to be exact — but instead of dissolving into absurd reality, he survived, emerging even more legendary than before.

So perhaps he didn’t want to die but was seeking another way to turn death into art. For Dalí, death wasn’t an end, merely an illusion perfectly suited to his genius.

Where Psychoactive Substances Meet Genius: From LSD to Masterpieces

Had Salvador Dalí not been an artist, he might have been a professional chemist or a dealer of psychoactive substances, for genius and altered states of consciousness weren’t just inspirations but full immersions into realities where physics and logic could be dismissed. Dalí didn’t merely use such substances; he created his own universe through them.

For Dalí, LSD, cocaine, and marijuana weren’t just substances — they were tools with which he constructed his masterpieces. And it might all sound absurd if not for one thing: he believed these substances granted him access to the depths of the human psyche and the universe itself.

He openly claimed his art was impossible without these substances. In a 1971 interview with Le Figaro, he remarked, “I’ve seen the world like no one else, and only through these substances have I reached such heights in art.” He insisted LSD allowed him to perceive “invisible structures” he then translated onto his canvases.

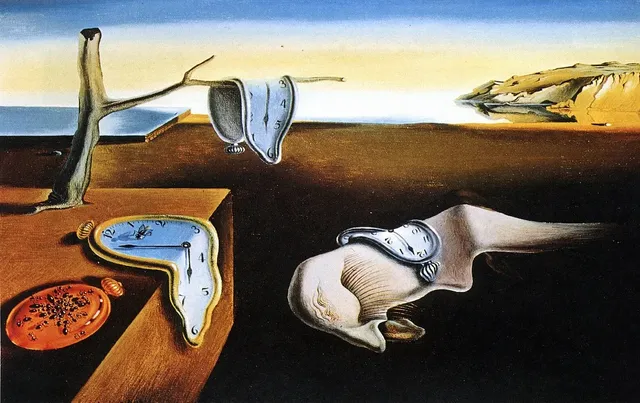

Dalí didn’t merely use substances for inspiration; he wove them into his creative philosophy, seeing them as a gateway to another dimension of perception and new layers of reality. This belief was reflected in his works, such as The Persistence of Memory (1931), with its iconic melting clocks, inspired by hallucinatory experiences.

Gala: Love, Betrayal, and Psychological Warfare on Canvas

Gala Éluard: The Woman Who Was More Than Salvador Dalí’s Wife

Gala Éluard wasn’t just Salvador Dalí’s wife. She was his personal chef, psychotherapist, producer, and, at times, his maid. But more importantly, she became his shadow — a tyrannical manager of his inner world and, occasionally, just a wife who ensured her husband kept painting rather than lingering in cafés, sipping coffee, and philosophizing. Dalí was the artist; Gala was his eternal “investor.” He was the genius, and she knew how to extract the maximum profit from his brilliance.

But let’s not romanticize this duo. Yes, she was his “muse,” but inspiration is usually thought of as a muse whispering elegant and lofty ideas. Gala didn’t whisper — she dictated, sometimes right to his face. She resembled a director deciding which of your movies would be a “hit” and which would leave audiences weeping with disappointment. Gala even made duplicates of Dalí’s paintings, sewing his signature onto them as if she were monetizing his art. That’s creativity for you!

Fans of Dalí probably had no idea their beloved genius was trapped by a woman who, in essence, turned his brilliance into a business venture. He signed her copies, and it was like an artist being handed an idea for their next hit and agreeing to it just to maintain their image. Who says even great artists can’t be psychologically dependent on women just like any other man?

Here’s another detail: Gala wasn’t faithful to her genius husband. She had flings left and right, as though it were part of her daily routine. Yet, instead of jealousy, Dalí seemed more concerned about maintaining his share of fame and success. After all, who else but his wife could so skillfully manipulate his life? If she’d been in charge of “sales management,” Dalí’s genius would have been the brand, and Gala the CEO. The perfect team, wouldn’t you agree?

Rather than suffer over her affairs, Dalí incorporated them into his art. Perhaps he was the only person who could treat infidelity as a “creative stimulus” rather than a reason for scandal. His painting was his life, and Gala was part of it. If this absurdity were a comedy, we’d laugh. But since it was more than absurdity — a reflection of his psyche — laughter sticks in the throat.

Gala was like a shadow that followed him everywhere, never letting him forget that, yes, he was a great artist, but she would always stand in his way. She was his inspiration — but an inspiration with a lock on his neck. She was his freedom, but only within her world, where “artist” was merely a title, not a reality.

So, dear Dalí fans, don’t think his genius was solely a matter of talent. It was a strategy. Her name was Gala, and she decided she would run the theater called “The Life of Salvador Dalí.” Our hero, of course, signed the paintings as if he saw no issue with it. Gala made him a genius — and that was enough.

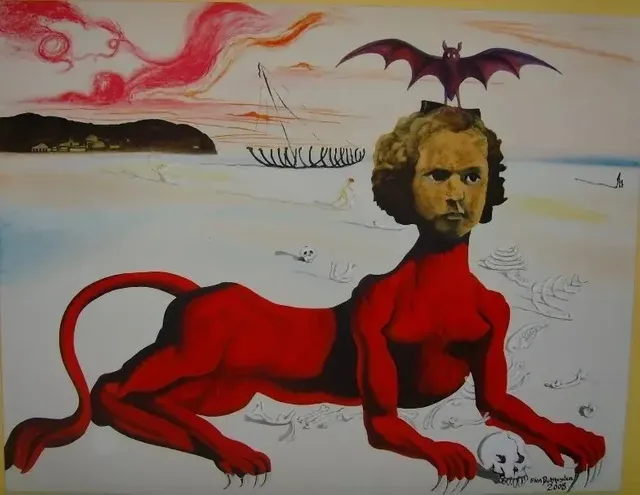

Dalí’s Transgender Love: He Painted More Than Women

Salvador Dalí wasn’t just an artist; he was a true troublemaker in the world of art. Instead of painting dull portraits of women holding flowers and fruit, he decided to expand his horizons. “Why not depict people whose bodies defy stereotypes while carrying it off with incredible style?” Dalí thought. And guess what? He did it — painting not only women but also men in women’s clothing and even — brace yourselves — transgender individuals. This wasn’t merely the modernist era; this was transformational art drama at its finest.

Oddly enough, Dalí foresaw it all. In his world, gender wasn’t a category, just as nothing else was. He painted men, women, and beings tangled in their gender roles. All of this was part of his “art of absurdity,” where boundaries held no significance. After all, why not paint a woman who was, in fact, a man? His ideal canvas for this was Thelma Temple. She was his model, and rumor has it, more than just a model. The problem? Thelma was a transgender woman who, despite surgeries and hormone therapy, didn’t fit the traditional “woman” mold for many. For Dalí, this was the perfect opportunity to defy moral conventions.

In 1936, Thelma posed for Dalí, and he painted the artwork “The Luminaries of Dreaming,” where her depiction was so absurd you’d hesitate to search online to discover what kind of “otherworldly being” this was. Yes, she looked like a creature transcending all rules, and that’s exactly what Dalí wanted. Thelma’s portrait wasn’t just a painting; it was a challenge to society. It didn’t matter whether you were male or female — what mattered was being whoever you wanted to be. Do you get it? No? Well, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that Dalí believed gender distinctions were trivial when it came to true art.

And here’s where the drama intensifies. Dalí wasn’t just breaking boundaries; he toyed with them like a child with toys. He created paintings that seemed to contradict reality, asserting his complete independence from societal norms. Blurring boundaries — that’s what art was for him. And if Dalí could paint and depict transgender models, it wasn’t because he was “inclusive,” but because, like with Gala, he was a master of absurdity and turned that into art. Why stick to stereotypes when you can redraw the world?

As art historian Jonathan Burns noted in his study “Dalí’s Subversive Art: Gender and Identity” (2012), Dalí’s work wasn’t merely a reaction to society — it was an attempt to dismantle it. He knew no limits and proved that if you want to be a genius, you shouldn’t just break walls — you should incorporate them into your foundation. The example of Thelma Temple and other models wasn’t just art drama; it was a challenge to a society so used to caging people. Dalí set them free.

Now imagine: the 1930s, a time when people were still stuck in their suits, afraid to even think about something as abstract as gender identity. And here comes Dalí, painting how all a man in a dress lacks is a predatory glare and a manicure to become the ultimate ideal. But what about us, people of the 21st century? That same Dalí, who painted trans individuals, would be more relevant now than ever. So if you ever thought Dalí was just a mustachioed madman, maybe it’s time to rethink your life.

How to Shock the World: Dalí’s Extravagant Public Stunts

If Dalí lived today, he’d undoubtedly be a Tik Tok star. Who needs influencers when you have someone who staged real-life spectacles worthy of an episode from American Horror Story? Dalí understood that shock wasn’t just a way to grab attention — it was an art form, truly provocative and delightfully outrageous.

Picture this: 1936, Salvador Dalí takes the stage at the opening of his New York exhibition, surrounded by people only beginning to grasp that reality and absurdity are two inseparable parts of the universe. What does Dalí do? He doesn’t merely greet the guests. He appears in a costume resembling a fairy-tale monster, sporting oversized mustaches that could double as weapons of mass destruction. His appearance at the time? The pinnacle of absurdity. The audience must have felt like they were in a nightmare, and Dalí knew exactly how to ensure that effect. Simply because he wasn’t just an artist — he was a true master of reality manipulation.

Another unforgettable moment: his famous interview where Dalí, for the sake of extra flair, pretended to be hypnotized. Immersed in a trance, he spoke to each person as if they were a being from a parallel universe. His facial expression resembled someone who’d just walked out of a psychiatric hospital he himself designed. The interview became not just a conversation but a full-blown performance for the world. The best part? The audience (and journalists) never knew what to expect: one moment, Dalí was an ego explosion; the next, a bizarre creature somehow delighting everyone around him.

During one public appearance where he was supposed to talk about a painting, Dalí chose an unconventional approach. Instead of explaining its meaning (far too dull for Dalí), he made long, dramatic pauses, as if every minute of silence was the answer to the universe’s most philosophical questions. Students and intellectuals of the time couldn’t decipher whether it was a joke or an attempt to “liberate” them from traditional perceptions of art. Likely, both interpretations were correct. His shocking performances left an unsettling feeling, like waking up from a nightmare that never ends.

Of course, we can’t forget his infamous self-portrait in a “black suit” and catlike appearance — how could anyone forget that image? There he was, sitting among his paintings with a facial expression beyond words, as if he was about to blow up the very concept of “normality.” His painting “Cat Whiskers” (1942) came with a signature that felt like a contract with an otherworldly realm where no logic or laws existed.

For Dalí, extravagant antics weren’t mere moments — they were an art form in themselves. His behavior was like a drug — first shocking, then addictive. Dalí knew how to “sell” his image as shock therapy, leaving everyone clueless about what might come next. Who else but Dalí could manipulate all the rules like that?

If you think Dalí’s extravagance was just for attention, you’re mistaken. It was a calculated effort to dismantle the established rules of art and life. His public appearances became performance art that both shocked and inspired.

Salvador Dalí — The Artist Who Deceived Reality and Himself

Salvador Dalí wasn’t just an artist; he was a manipulator of reality. He didn’t merely break stereotypes — he chewed them up, spat them out, and then painted them with a grin, morphing them into melting clocks. Reality? Nonsense. Psychology? The process of twisting reality into absurdity. Everything Dalí created was an attempt to strip familiar concepts of their essence, leaving only their shell — bright, distorted, and fractured.

But here’s where the real drama begins. Dalí wasn’t just a master of illusion; he was the worst kind of deceiver to himself. By crafting images that shattered everything we thought we knew about normalcy, he trapped himself in his own mirages. He became part of his own show, locked in a gilded cage of absurdity that he built with his own hands.

Think about it: his paintings weren’t just art. They were an escape — from himself, from the norms and rules that bind humanity. In his world, nothing was stable: not time, not space, not people. Dalí was an artist who painted a trap for himself and then fell into it. He deceived not just reality but himself, convincing the world that his bizarre shapes and distorted figures were the pinnacle of art. Deep down, he was the same boy afraid the world might see him as anything less than what he wanted to be. An artist who created absurdity couldn’t escape it himself.

And yet, Dalí remained the master of his own mad illusions. His sculptures weren’t just representations; they were extended forms of his cartoonish fantasies. He created “looped” figures, “stretched” metals, and such deformed shapes that, if they existed in reality, you’d think someone had been playing with “Inverted Worlds” and geometry with obsessive perfection. These sculptures were like cries for help from a man who had become part of his own insane world. And all of this was underscored by his giant melting clocks, dissolving like the very idea of stability in modern society. A rubbery reality stretched so thin that a mere breath might tear it apart.

Dalí’s sculptures were a deception, played not just on the viewer but on his own soul. He could have turned them into masterclasses on how to “bury” one’s fears, only to recreate them as distorted, fake images for public display. Instead, he chose a convoluted path: one of self-absorbed illusion. He didn’t just paint — he manipulated space and time, toying with their perception until even he was lost in his own distortions.

The result? We see Dalí as a great master of absurdity, but beneath the layers of mystification lies a man who never learned to understand himself. He turned his life into a meaningless performance, with every step an attempt at self-expression in a world where reality and its distorted counterpart were indistinguishable. This tragedy, this futile escape from himself, ultimately became part of him.

So, perhaps Dalí deceived reality, but he could never deceive his own soul. He created illusions and captivated the world with them, but in the end, he became a prisoner of his own absurdity. An artist who forgot that his art couldn’t save him from himself.

Eternity on Canvas and Loneliness in Life — How Dalí Became a Living Myth and Died in the Shadows

Salvador Dalí died in 1989, seven years after the death of his wife, Gala. His final years were filled with tragedy and loneliness. After Gala passed in 1982, Dalí’s strength waned, and his life plunged into the dark waters of depression and illness. In 1984, he suffered severe burns, further deteriorating his health, and he rarely left his home from that point onward. The emotional devastation and the loss of Gala were nearly fatal blows for him.

Dalí teetered on the brink of madness, and his health continued to decline. He spent his final years in his castle in Figueres, Spain, suffering from mental and physical ailments under the constant care of nurses and doctors. He often complained of loneliness yet continued to create art that, like his final works, reflected his inner aggression and despair. One of his last pieces, Two Nightstands and a Bed Violently Attacking a Cello, was filled with rage and aggression, which, according to friends, mirrored his state of mind at the time.

Thus, Dalí’s final years were marked by illness, solitude, and dissatisfaction. Despite his eccentric and grandiose life, he ended up alone, lost in a world he had created for himself.

Dalí for Millions — How Insane Prices Keep Him Immortal

Salvador Dalí’s paintings continue to command astonishing prices at auctions, reinforcing his status as one of the most sought-after artists in the world. For example, his iconic The Persistence of Memory sold for $75 million in 2024, highlighting both the artistic and cultural significance of the piece. Other works by Dalí have also fetched staggering sums. Printemps Nécrophilique sold for £10 million (approximately $16.3 million) at a Sotheby’s auction in 2012. Additionally, Couple with Their Heads Full of Clouds was auctioned for nearly £8.2 million ($12.8 million) in 2020.

These prices not only affirm the value of Dalí’s art but also demonstrate how his vision continues to captivate collectors and remain relevant in our time.

Dalí — Art or Just a Brilliant Performance Stunt?

And so, we arrive at the finale of this absurd comedy, where the character became larger than the art itself. Dalí was a master of what we now call “performance art.” His life wasn’t just surreal; it was an openly cynical, manic game of truth and fiction. He created a myth around himself and then sold that myth for exorbitant sums, even signing paintings he didn’t create. Ironically, this may have been the only true masterpiece he ever made — the cult of his own personality.

So, if you ever dream of becoming great, remember: all it takes is eccentricity, unreliability, and a touch of madness, and the world will build an art market around you. Salvador Dalí simply figured it out before anyone else.

Has this story inspired you? Share your thoughts in the comments and don’t forget to subscribe so we can discuss important topics together! 💬