Malaysia: The Monkey Cave that echoes Sufism

This spring break I visited incredible Malaysia and this blogpost makes a small window into some of my experiences that I wanted to connect with our class material.

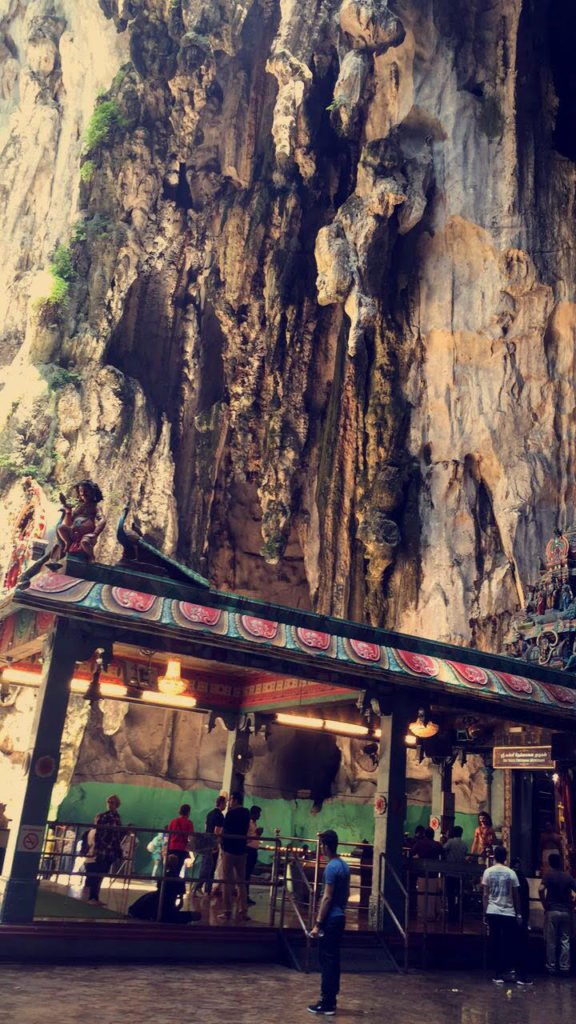

One particular excursion will be the focus of my blogpost – my short trip to the Batu cave, one of the most famous Hindu temples outside of India.

After reading Haroon Khalid’s incredibly insightful book, “In Search Of Shiva”, I wanted to dedicate this post to peculiar links I have seen in the culture of Sufi shrines in Pakistan and the Batu cave temple in Malaysia, with a particular focus on syncretism used in both religious streams. I am also attaching my personal photographs and a short video to paint a better picture of what I have observed during my short (scratching-the-surface) visit.

Given that the grandiose Batu cave, carved into the peaceful greenery of Malaysia’s famously lush nature, is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Malaysia next to exotic beach resorts and the urban heat of Kuala Lumpur, this inviting and widely publicized narrative of the temple deviates from the almost hidden nature that encapsulated Sufi shrines across Pakistan. This especially refers to deeply hidden shrines that Haroon Khalid goes after in his book “In Search Of Shiva” that require a very insightful, sophisticated and, to an extent, insider knowledge and connections to be located and then visited. In other words, I assume a lot of planning and phone calls go into each visit story in the book.

On the other side of the spectrum, not all Sufi shrines have the same exposure to the world and not all are secluded and hidden away from the eyes of ordinary tourists and outsiders to their local communities. Many have been written about in globally acclaimed newspapers and presented in documentaries. In this regard, many Sufi shrines do come from the same background of wider acclaim as the Batu cave temple in Malaysia.

An important note to mention here is that the Batu temple is partially funded by tourist donations and local vendors that have attached themselves to the popularity of the temple under the hot Malaysian sun.

The historical background of the Bate cave temple does not differ that much from the originating stories of numerous Sufi shrines, except that it is founded on an idea by an Indian trader who was inspired by the shapes of the cave arches to form a temple at the site. In other words, its origins and history are a bit more secular in nature than most Sufi shrines that I have read about, given that it has no holy figure attached to its origins. Given that this seat is empty, it was interesting to note a question to myself as I went through the temple: how much significance does a founding figure play in the self-sustainability of the place years and centuries after? I am yet to answer this question fully.

The first thing that reminded me of Haroon Khalid’s book adventures in his quest for the Sufi shrines across Pakistan are the monkeys that are roaming around free and intermingling with curious and somewhat appalled tourists who did not quite know what category to put them in. The temporary-looking shops that glued themselves to the base of the temple sold food for the monkeys and groups of tourists competed who would feed more. The play between the animals and the curious hordes of newcomers on the steep steps towards the biggest cave was almost distracting me from the holiness of the temple.What this reminded me of is the dog shrine in Khalid's book that made me, as a Muslim, think of how much it differs from what I understand Islam to be. Opposed to that are the freely roaming monkeys at Batu caves whose significance comes from Hinduism itself. The question I had for myself as I was looking at the monkeys half-scared to approach was: does the backing of religion give the animal more legitimacy to be at the temple / shrine? Perhaps this leads to syncretism in Sufi shrines that have borrowed from the folk culture of South-East Asia and its Hindu remnants. In a way, the people who believe in Sufi shrine culture were not afraid to incorporate their local beliefs, which have been influenced by Hinduism, into what they thought is their own version of Islam. How beautiful is it to make your religion closer to your specific context by incorporating a part of your societal heritage into it? Obviously, this leads to a perversion and desecration of religion, according to some. I find it fascinating.

To go back to my tour of the Batu temple, the inside of the biggest cave, starting from a moist platform that consumes you after the last of the 1000 steps, was covered by the rich stalactites of the cave. Raindrops would fall on you as you come closer to the colorful Hindu points and sense the incense and the see the lit candles. Many old Hindu ladies in colorful saris would blend in with the warm colors of the temple posts, differentiating themselves from the dreary color of the dark inside of the cave. The atmosphere in the air and the biosphere of the space change with the entrance to the cave. The path then leads you to the next cave and the next temple. One of the caves has a museum inside that organizes hourly tours to see the animals that reside in it – including many types of bats whose pictures and latin names are exhibited at the entrance of the make-shift museum.

This temple was an overly commercialized version of the Sufi shrines from Khalid’s book, such that they actively worked on acquainting curious tourists with the significance of the temple and the historical location of the cave – all in one, as opposed to the described Sufi shrines in Pakistan that cohabitate with their local communities, mostly not concerning themselves with tourists and outsiders.

I also created a short video in the biggest cave.

Overall, what I found interesting are the quiet and nonintrusive spaces for worship that the temple created among massive numbers of tourists who were clearly not there for religious purposes.

What is further interesting is the implicit connection I saw with a Hindu temple in Malaysia and Sufi shrines in Pakistan. Orienting themselves to two different religions, the two families of temples and shrines do share plenty in common. Neither group finds itself currently belonging to the dominant culture of the place they are located in. And although they represent Islam and Hinduism, respectively, they share the same spiritual atmosphere and draw from similar traditions, starting from the presence of animals at the temple / shrine and their almost unquestionable legitimacy at the spaces of both religions. The similarities alude to what I was mentioning in one of my previous paragraphs - the flow of influence between the two religions is remarkable. And it speaks to how fluid one's interpretation and everyday application of religion can be. It also speaks to the significance and the role of historical influences of other (older) religions on the new ones, the young one in this particular example being Islam.

After my visit to Batu caves, I definitely want to explore more on explicit connections and historical influences between specific Hindu temples and Sufi shrines in Pakistan and the fluid bond between their historical and current legacies.

Sources:

Khalid, Haroon; "In Search Of Shiva"

Interesting thoughts

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://wp.nyu.edu/muslimpop/2017/03/28/malaysia-the-monkey-cave-that-echoes-sufism/

Wow, this was so interesting to read! Thank you for a good story, and welcome to Steemit :)