Earth is becoming 'Planet Plastic

US scientists have calculated the total amount of plastic ever made and put the number at 8.3 billion tonnes.

It is an astonishing mass of material that has essentially been created only in the last 65 years or so.

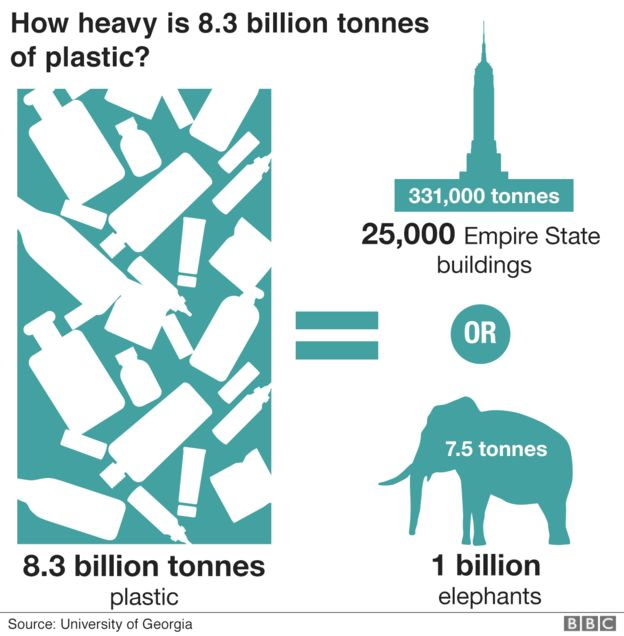

The 8.3 billion tonnes is as heavy as 25,000 Empire State Buildings in New York, or a billion elephants.

The great issue is that plastic items, like packaging, tend to be used for very short periods before being discarded.

More than 70% of the total production is now in waste streams, sent largely to landfill - although too much of it just litters the wider environment, including the oceans.

"We are rapidly heading towards 'Planet Plastic', and if we don't want to live on that kind of world then we may have to rethink how we use some materials, in particular plastic," Dr Roland Geyer told BBC News.

A paper authored by the industrial ecologist from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and colleagues appears in the journal Science Advances. It is described as the first truly global assessment of how much plastic has been manufactured, how the material in all its forms is used, and where it ends up. Here are some of its key numbers.

8,300 million tonnes of virgin plastics have been produced

Half of this material was made in just the past 13 years

About 30% of the historic production remains in use today

Of the discarded plastic, roughly 9% has been recycled

Some 12% has been incinerated, but 79% has gone to landfill

Shortest-use items are packaging, typically less than a year

Longest-use products are found in construction and machinery

Current trends point to 12 billion tonnes of waste by 2050

Recycling rates in 2014: Europe (30%), China (25%), US (9%)

There is no question that plastics are a wonder material. Their adaptability and durability have seen their production and use accelerate past most other manmade materials apart from steel, cement and brick.

From the start of mass-manufacturing in the 1950s, the polymers are now all around us - incorporated into everything from food wrapping and clothing, to aeroplane parts and flame retardants. But it is precisely plastics' amazing qualities that now present a burgeoning problem.

None of the commonly used plastics are biodegradable. The only way to permanently dispose of their waste is to destructively heat it - through a decomposition process known as pyrolysis or through simple incineration; although the latter is complicated by health and emissions concerns.

In the meantime, the waste mounts up. There is enough plastic debris out there right now, Geyer and colleagues say, to cover an entire country the size of Argentina. The team's hope is that their new analysis will give added impetus to the conversation about how best to deal with the plastics issue.

"Our mantra is you can't manage what you don't measure," Dr Geyer said. "So, our idea was to put the numbers out there without us telling the world what the world should be doing, but really just to start a real, concerted discussion."

The Inquiry: Time to ban the plastic bottle?

A mission to the Pacific plastic patch

Plastic heading for oceans quantified

Plastic-eating caterpillar 'may cut waste'

Recycling rates are increasing and novel chemistry has some biodegradable alternatives, but manufacturing new plastic is so cheap the virgin product is hard to dislodge.

The same team - which includes Jenna Jambeck from the University of Georgia and Kara Lavender Law from the Sea Education Association at Woods Hole - produced the seminal report in 2015 that quantified the total amount of plastic waste escaping to the oceans each year: eight million tonnes.

This particular waste flow is probably the one that has generated most concern of late because of the clear evidence now that some of this discarded material is getting into the food chain as fish and other marine creatures ingest small polymer fragments.

Dr Erik van Sebille from Utrecht University in the Netherlands is an oceanographer who tracks plastics in our seas. Of the new report, he said: "We're facing a tsunami of plastic waste, and we need to deal with that.

"The global waste industry needs to get its act together and make sure that the ever-increasing amounts of plastic waste generated don't end up in the environment.

"We need a radical shift in how we deal with plastic waste. On current trends, it will take until 2060 before more plastic gets recycled than landfilled and lost to the environment. That clearly is too slow; we can't wait that long," he told BBC News.

And Richard Thompson, professor of marine biology at Plymouth University, UK, commented: "If plastic products are designed with recyclability in mind they can be recycled many times over. Some would say a bottle could be recycled 20 times. That's a substantial reduction in waste. At the moment poor design limits us."

To illustrate that point, Dr Geyer said: "The holy grail of recycling is to keep material in use and in the loop for ever if you can. But it turns out in our study that actually 90% of that material that did get recycled - which I think we calculated was 600 million tonnes - only got recycled once."