What Do Cicadas Know About Prime Numbers And Math? (And Why Do Their Butts Sometimes Fall Off?)

Periodical cicadas (or Magicicada) are a genus of insects that live in the eastern parts of North America. What makes them particularly interesting are their long finely-tuned lifecycles.

Periodical cicadas spend most of their lives underground feeding on plant juices and they only emerge once in their lifetimes to breed. But this doesn't happen every year like it does for many other cicada genera but precisely once every 17 or 13 years depending on the species. All the cicadas from a single brood emerge simultaneously and mate which affords them some evolutionary advantages that we'll talk about below. While they spend most of their lives underground feeding on plant roots, they all emerge together, sing their signature mating calls, lay their eggs on tree branches and die within two weeks of their emergence. When their eggs hatch, they immediately go back underground and start the cycle all over again.

What's really fascinating here are the reasons behind the periods being 17 or 13 years exactly instead of say 12, 15, or 16. Anybody that likes math has probably already noticed that 13 and 17 are prime numbers while the other options mentioned aren't. But why would this relatively simple bug genus care about math like that?

Let's tackle the questions about periodical cicada's lifecycles one by one. (Butts falling off will be tackled last.)

Why Do Periodical Cicadas Have Such Long Synchronized Lifecycles?

While the cicada nymphs are living underground, their lives are pretty safe. They have an abundant enough food supply in plant roots to extract nutrition from and they have relatively few predators like moles who are not having the easiest time finding them underground. But in order for the cicadas to reproduce, they need to find mates from the opposite gender and that would be as hard to do for them underground as it is for the moles.

When the insects emerge above ground they become easy prey for a much wider variety of predators like birds, reptiles and mammals. If different individuals were emerging at random times, there would always be hungry predators around to gorge on them and survival of the species would be difficult. But when they all emerge at the same time en mass, their numbers are so high that predators simply don't have the capacity to eat all of them. And after all of the predators have had their fill, there are still plenty of adult cicadas that survive and reproduce.

This antipredator survival strategy is called predator satiation and it's used by all kind of prey species around the world in one form or another to ensure enough individuals survive to reproduce.

A cicada killer wasp with a cicada (Source)

Now, if this process repeated every year or had a much shorter period, it would be possible for predators to start depending on it for their own survival and to have their own lifecycles synchronized with this abundant periodic food source. This would allow them to reproduce in higher numbers to take advantage of the period of abundance which in turn would make the strategy less effective as a higher percentage of the emerging individuals would be eaten and would not get to reproduce. We can see this happen in nature in contexts like bears depending on trout migrations or the cicada killer wasp that depends on non-periodical species of cicada to provide food for their young.

What the wasp does is synchronize their own mating periods with the emergence of local cicada species with one-year lifecycles. The female wasps catch and kill cicadas and drag them into their ground burrows where they lay their eggs. This affords their offspring something to feed on when they hatch. Having a lifecycle that's much longer has allowed periodical cicadas to avoid this type of synchronized predation to develop based on them.

But this still doesn't answer another larger question about the mathematical significance of their lifecycle lengths.

Why Are Their Lifecycles Prime?

The most interesting question here is what the specific benefit of having those long lifecycles being prime instead of just any number in the 10-to-20-year range is. It's surely equally difficult for a wasp to evolve a 14-year lifecycle as it is for it to evolve a 13-year lifecycle, so why favor one over the other? Or is this just random coincidence that we see significance in because we understand math while the cicadas fell into it by sheer chance?

Besides sheer chance, there are two main hypotheses that try to explain why this is happening and why periodical cicadas favor prime lifecycle lengths so clearly.

1. It helps avoid regular peaks in predator populations

One of the hypotheses that might help us shed some light on the question is that this is a way to avoid accidental or partial synchronization with predators. Besides the cicadas, there might be other species that provide better opportunities for predators on periodical basis but they usually happen on a much shorter scale. This means that the number of predators can often fluctuate with a stable periodicity of 2 or 3 years (usually up to 5). This means that the number of predators out there could be the highest every 2 or 3 years. If the periodical cicada's lifecycles have that number as a multiple, once they coincide with the larger numbers of a certain predators, they will remain in sync and the cicadas will regularly have a higher percentage of the emerging individuals become food for them instead of procreating.

Let's imagine two hypothetical cicada broods with a 12-year and a 13-year lifecycles. If they emerge in the same year together with a higher number of predators with both 2-year and 3-year periodicity, both broods will suffer from decreased survival rates due to predation. But for their next emergence the 12-year cicadas will again be plagued by the same problem as predators with periods of 2, 3 and even 4 years would again be hitting their periodic population peaks. The 13-year cicadas, on the other hand, will immediately fall out of sync and will have a better chance to recover and thrive in the long run.

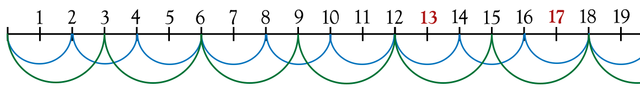

The graph above demonstrates how prime numbers like 13 and 17 fall out of sync with both 2 and 3 year periodicity and the same will be true if we added even longer repeated periods like 4, 5, 6 or 7 years to the graph. This suggests that even after significant predation and decreased survival rates, having a long lifecycle based on a prime number is more likely to give a chance to the brood to recover without allowing predators to thrive and increase in numbers regularly based on them.

But could this be the only explanation? There is actually a more widely accepted hypothesis.

2. It helps avoid detrimental hybridization between different periodical cicada species

One of the most important factors to ensure that the survival strategy of predators satiation works well is that the whole brood emerges en masse at the same time. When individuals fall out of sync with the rest, this drastically decreases their chances of survival. If they emerge too early, predators will still be hungry and if they emerge too late, predators would have had enough time to digest their brothers and sisters and would already be looking for their next meal. If the difference is emerging a year or two earlier or later, surviving predation would not be your only concern. Even if the individual doesn't get eaten, they would be much less likely to find a suitable mate. This means that being out of sync with the rest of your brood significantly decreases one's chances of successful procreation.

Synchronization between individuals from the same brood is vital to the brood's well-being and survival. What can get that out of whack is hybridization between different periodical cicada species. When two species prone to hybridization share a habitat, their survival partially depends on the times of their emergence not overlapping as that can result in a lot of their offspring becoming out of sync with their main brood. This means they will have lower chances of procreating themselves because predator satiation will not work that well for them and they will have fewer mates available even if they don't get eaten by something else.

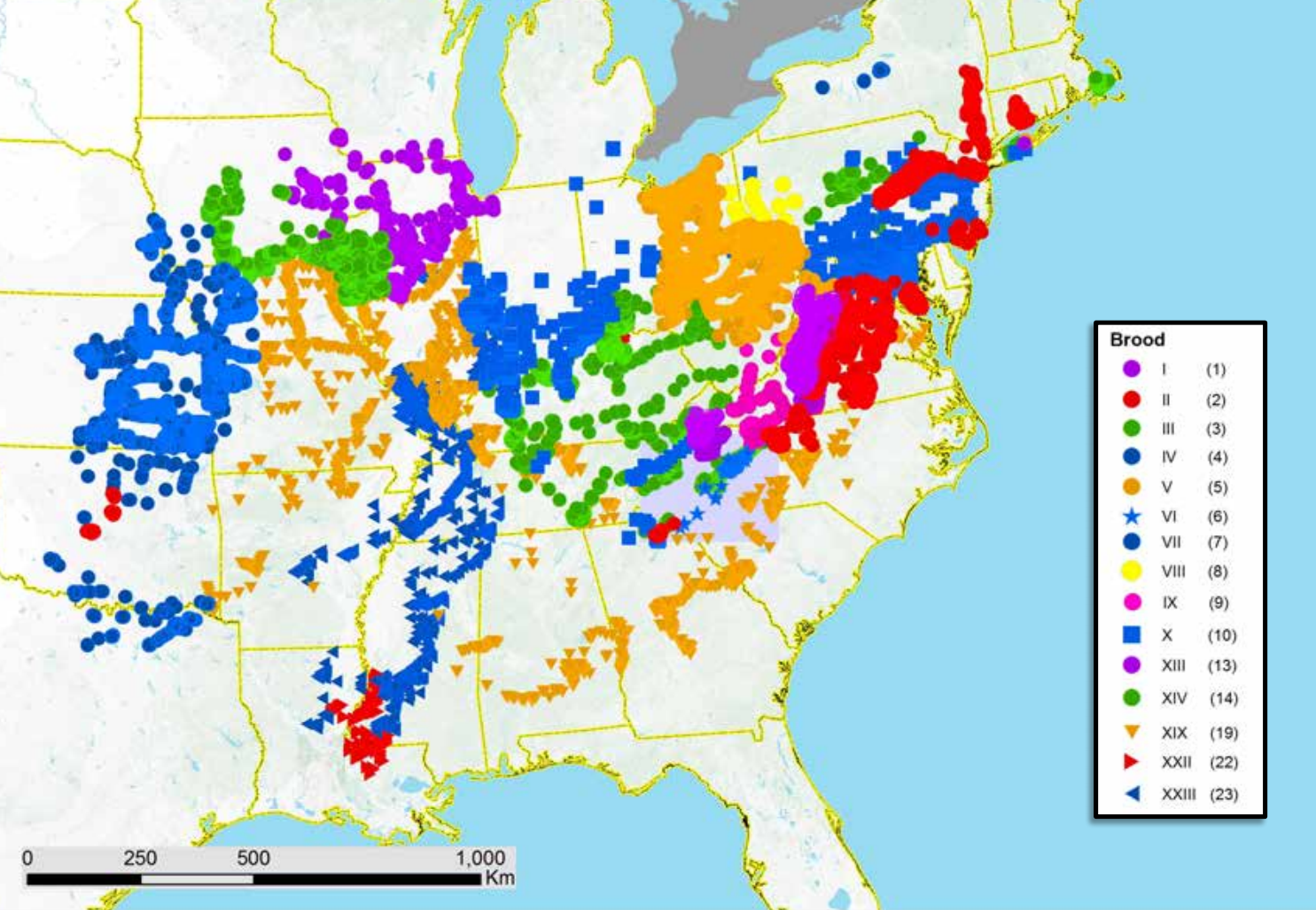

Geographical distribution of periodical cicada broods (Source)

What ensures the lowest chances of two species with lifecycles of different lengths emerging at the same time would be for both lengths to be prime numbers. And since the periodical cicadas of North America tend to live close enough to each other for hybridization to be a real danger, it might be something that has applied strong selective pressure for individuals to develop prime-number lifecycles.

There have been mathematical models and simulations done to show that this is likely to be the case, but it's easier to understand its significance with a simple example. If there are two species of cicadas with overlapping habitats, if their lifecycles are 12 and 16 years respectively, they will emerge together every 48 years. The two numbers have common multiples which makes synchronization easier and more common. But bump up those numbers up by one to 13 and 17 and the two species will emerge together only once every 221 years (the product of 13 x 17). This decreases the chances for hybridization significantly which allows the broods to stay well-synchronized internally. This is crucial for their survival strategy of predator satiation to work well for them. When they don't get genes from other species into their gene pool, they can remain synchronized without unexpected genes leading to non-desirable emergence schedule changes or sterility.

So Which One Is It?

Since the exact mechanisms and the genes that determine the lengths of the cicada's lifecycles are yet not fully understood, none of those hypotheses has been confirmed with high degree of certainty yet and it's probable that both factors play some part in the process. But it's clear that prime numbers give periodical cicadas higher chances of survival and this can also be illustrated by what happens to stragglers.

Stragglers are individuals that emerge too early or too late. Most of the time when stragglers occur, they emerge either 4 years too early or four years too late. It's believed that 13-year and 17-year lifecycle periods both result from versions of the same gene, so it shouldn't be surprising to find that most stragglers from 13-year species emerge 4 years too late (after 17 years underground) while most stragglers from 17-year species emerge 4 years too early (after 13 years underground). Most of the time stragglers do not lead to sustainable populations and they might sometimes pose additional danger as they offer up more chances for hybridization between different periodical cicada species.

Still, there are stragglers that might emerge anytime in the 9-to-20-year range, but only the 4-year ones that have also come upon prime numbers have any chance of long-term survival. This helps illustrates the stability of the prime numbers 13 and 17 for periodical cicadas regardless of the exact processes that brings it about.

Something else might also happen when stragglers appear in large enough numbers for them to manage to avoid predators and procreate. For instance, if a large enough group of members of a 17-year species emerges in 13 years and reproduces in sufficient numbers, their offspring might emerge in 17 years again, forming a new brood. The process of a group of stragglers managing to establish a stable new brood is called acceleration. It's believed that a number of the existing periodical cicada broods have been created through this process . Nowadays, stragglers have a lower chance of successful acceleration due to human activity and deforestation.

But Something Still Found a Way to Specialize in Feeding on Periodical Cicadas

While animals (be it birds, lizards, mammals, or other insects) might have a hard time keeping up with periodical cicadas, there are organisms that have cracked their mathematical code and have successfully specialized in feeding on them - fungi. Massospora cicadina is a fungal pathogen that infects a number of cicada species including periodical cicadas. The spores of this species can remain dormant for long enough for them to be able to wait out the cicadas' long lifecycles. When they emerge from the soil, the spores infect them and start developing in their abdomens. The fungal infection usually grows so much that the rear segment of their exoskeleton detaches from their bodies. In other words, the insect's butt literally falls off.

The fungus renders the infected cicada infertile, but it continues to live with the exposed fungal growth in place of it's posterior for an extended period of time. While the insect is flying around, the fungus actively discharges spores covering the ground in them. The spores can then patiently wait 13 or 17 years for the next generation to emerge so they can in turn get infected too. Regardless of the mathematical nature and length of the periodical cicada lifecycles, this is something they simply can't escape in the same way that they escape animal predators.

This is yet another illustration of how life always finds a way and how survival is a constant arms race between different species. And while every strategy has its merits and benefits, there is always a chance that something else will find a way around it.

Sources:

- http://magicicada.org

- http://www.cicadamania.com/cicadas/cicadas-and-prime-numbers/

- http://www.cicadamania.com/cicadas/what-are-stragglers/

- https://cims.nyu.edu/~eve2/cicadas.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2690011/

- http://www.cicadamania.com/downloads/prime-PRL.pdf

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-19813-0

Awesome post. I never new the 13 and 17 year lifecycles had purposes that could be explained mathematically.

I'm glad you liked it! Thank you for stopping by! :)

Excellent and informative. We hear these things every year here in the deep south. My son used to look up at the trees in the summer time and say, "munsters!"

That's great! :) I think the periodical cicadas in the south tend to be of the 13-year variety. Of course, there are also some species that emerge every year from different genera of cicada.

Very good publication and interesting rocking chair, I know that the cicadas are known for the sound they emit, this is thanks to the air sacs that are in the abdomen and that are inflated and deflated through the membranes that entomologists call timbales. And the power and intermittence of that sound is for some annoying people, it accelerates with the increase in temperatures. That is why we believe that cicadas sound with greater intensity during heat waves and in the central hours of the day. Thanks for the information since I did not know much about these insects. Thanks for this contribution. Regards

Thank you for the additional info!

P.S.: I laughed really hard when I saw that my nickname got autocorrected to rocking chair in your comment :D I love it :P I couldn't help but photoshop this:

Yes, the translation is impressive, I left it for you to see it, I invite you to see some of my publications to see what you think and comment. Thank you.

https://steemit.com/biology/@antoniodpz/harmful-or-beneficial-microorganisms

I learned a lot today. I knew about the 17-year cycle but not the 13. And I certainly didn't know about the fungus that makes their butts drop off! How cruel! You are sure you are not a science teacher?

I actually thought ESL for a few years and physics for one year at a high school at some point in my life.

Great informative post! The cicadas are coming out in a few months..can't wait love the sound.

I'm glad you think so and thanks for stopping by! :)

Wow! I wish you'd been my biology teacher! You made that really interesting! Maybe useful in one of my stories, actually. Came to this post following your curation by @MoxxyBot

Thank you for the kind words! I was a teacher for a bit but I only taught ESL and Physics.

Such a random topic to look in to and so interesting! Thanks :D

I'm glad you think so! Thanks for stopping by :)

Top effort, Dave. I learned a lot; and wasn't really expecting to, because bugs aren't really on my radar.

Very pleasantly surprised. Thanks.

I'm very glad to hear that! Thank you for stopping by and for giving those natural mathematician bugs a chance! :)

Holy cow, I learned so much just now! I never thought about cicadas as anything other than noisy. LOL

Awesome post!

I'm very glad to hear that! :) Thank you for stopping by! :)

Wow, what a great article. I didn't know any of these details about cicadas.

Nature can be pretty fantastic sometimes. The 13 or 17 year cycles sort of remind me of masting tree species that have light and heavy nut years so the animals that eat the nuts don't increase too much in number.

Thank you for stopping by! :) I do agree that those survival strategies have a lot in common, that's a very interesting nugget to learn about! :)