Barter to Money and the Empathy that a Lack of Numeracy Could Not Induce

Barter to Money and the Empathy that a Lack of Numeracy Could Not Induce

Introduction

The transition from barter systems to money-based economies represents one of the most significant changes in human history. Before the widespread use of money and numeracy, trade relied on empathy human beings understanding each other's needs and negotiating directly.

As money began to replace barter, the need for personal trust diminished, but without numeracy, people still struggled to calculate fair exchanges. This post examines how barter declined as money use increased, and how the lack of numeracy prevented the kind of trust and empathy that characterised earlier economic interactions.

The Role of Barter and Empathy

In early human societies, barter was the primary method of trade. Without a standardised medium of exchange, individuals and groups relied on empathy to ensure fair exchanges. A farmer trading grain for livestock, for instance, had to place themselves in the position of the other party, understanding their needs and ensuring mutual satisfaction. Barter was not just an economic exchange; it was a social interaction, built on trust and community.

However, as human societies grew more complex, the limitations of barter became evident. In large communities or long-distance trade, barter required precise knowledge of the value of goods, and the negotiation process became increasingly cumbersome. The introduction of money simplified this process, but it also began to erode the personal, empathetic connections that had been central to barter.

The Introduction of Money and the Decline of Barter

The first coins, minted in Lydia around 600 BCE, marked the beginning of a new era in economic exchange. Money allowed for standardised transactions, reducing the need for personal negotiation. The direct connection between traders, once mediated by empathy, became less important. Instead, the value of goods was abstracted into coinage, allowing trade to occur even between strangers with little trust between them.

While the introduction of money led to a gradual decline in barter, the process was slow. Barter persisted for centuries, particularly in rural areas or in times of economic hardship when coins were scarce. In medieval Europe, for instance, barter was still common among peasants, even as money became the dominant medium of exchange in urban markets. The rise of feudalism and the lack of widespread currency systems ensured that barter continued well into the Middle Ages.

The Importance of Numeracy

Though money simplified transactions, it did not entirely solve the problem of fair trade. Without numeracy, the ability to understand and work with numbers, many individuals were still vulnerable to unfair deals. Money alone could not induce the kind of empathy that was necessary for ensuring fairness in barter systems. The rise of numeracy, particularly in the 19th and 20th centuries, played a crucial role in levelling the playing field, allowing more people to engage in economic transactions with confidence.

Numeracy became widespread only with the advent of public education systems in Europe and North America. Before this, only elites, scribes, and merchants had the numerical skills required for complex trade. By the early 20th century, with numeracy becoming common among the general population, the need for personal trust and empathy in transactions diminished further, as individuals could now calculate value and fairness independently.

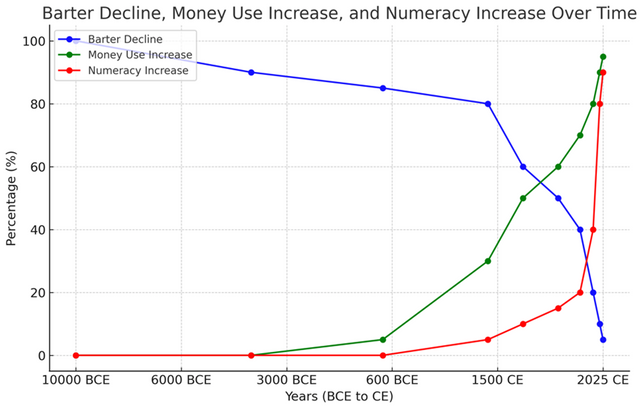

The Chart below shows Barter, Money and Numeracy in Use.

Barter, Empathy, and the Consequences of Their Decline

The decline of barter and the rise of money and numeracy represent more than just changes in how people traded goods. They mark a shift from a system based on human connection and trust to one grounded in abstraction and calculation. While the modern economy allows for efficiency and scale, it has also removed much of the empathy that once governed economic exchanges.

Barter required individuals to understand and relate to one another, making each transaction a negotiation not only of value but of social relations. The empathy exchanged in these interactions was a vital part of ensuring fairness, particularly in small, close-knit communities. As money and numeracy replaced this need, the personal connections that were once essential for trade were weakened, and economic transactions became increasingly impersonal.

Barter was extensively used up to and beyond 600 BCE, and even after the introduction of money, barter continued to be a primary method of exchange in many parts of the world for a significant period of time.

Key Points:

1. Barter Before 600 BCE:

• Prior to the invention of money around 600 BCE in the Kingdom of Lydia, barter was the predominant form of trade. Societies engaged in direct exchanges of goods and services because there was no standardised medium of exchange.

• Barter systems were used in local, small-scale economies, where personal relationships and trust were key to the success of each transaction.

2. Barter After 600 BCE:

• Even after the introduction of money, barter remained widespread, especially in rural and less economically developed regions. Coins and currency took time to spread and be adopted.

• Barter coexisted with early money systems for centuries. People continued to barter in areas where money was scarce or where trust between trading partners made it unnecessary to use coins.

• In more isolated communities, where currency was not available or widely trusted, barter remained the most practical form of exchange.

3. Gradual Decline of Barter:

• Barter declined gradually as coins, and eventually paper money, became more widely available and trusted. By the time of the Roman Empire (27 BCE – 476 CE), money had become a dominant medium of exchange in large urban centres, but barter persisted in rural areas and among the lower classes.

• Even into the Middle Ages (500-1500 CE), many regions, especially in rural Europe, still relied heavily on barter, especially in times of economic hardship or when currency systems were unstable.

4. Barter Today:

• While barter has declined to very small levels in the modern world, it has never disappeared entirely. Today, barter is sometimes used in localised settings, such as informal exchanges between individuals, bartering networks, or in times of economic crisis when cash is scarce.

• The rise of barter exchanges and platforms, especially online, has given barter a minor resurgence in modern times, though it remains far less significant compared to money-based transactions.

As such;-

• Barter was extensively used up to and beyond 600 BCE and continued to coexist with early money systems for many centuries. Its decline was gradual, and it still exists in some form today, albeit on a much smaller scale.

• The shift from barter to money-based economies was a slow and uneven process, as money took time to spread and gain widespread acceptance. Rural and less developed areas often held onto barter practices much longer than urban centres, where money facilitated larger, more anonymous transactions.

In Summary

The shift from barter to money-based economies was driven by the need for a more efficient and scalable method of trade. However, as this chapter has shown, this transition also led to the erosion of empathy in economic exchanges. Without numeracy, early money-based systems could not induce the same kind of fairness and trust that characterised barter.

Only with the widespread introduction of numeracy did individuals gain the tools to engage in fair trade independently. Yet, even today, the loss of empathy in economic transactions remains a consequence of this historic shift.

This chapter provides an analysis of the decline of barter, the rise of money, and the critical role of empathy in earlier economic systems. The accompanying chart visually illustrates the trends in barter, money, and numeracy over time.

Sources:

• Glyn Davies, A History of Money: From Ancient Times to the Present Day, University of Wales Press, 2002.

• David Graeber, Debt: The First 5,000 Years, Melville House, 2011.

• Joel Kaye, A History of Balance, 1250-1375: The Emergence of a New Model of Equilibrium and Its Impact on Thought, Cambridge University Press, 2014.

• Niall Ferguson, The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World, Penguin Press, 2008.

By Joe Bloggs

#Nostr pub key is: npub1yvlppcwga8k2qsvrh6rtd5cjv6hlmsm52uqsgw38yj36r4zu8wuqulu2dc

Bitcoin Address: 1DEEP7H4qrX7uCpqrx3sdkzGHeDV4L7fWT

Lightning Address: [email protected]