The Problem with “Great Schools”

If you have young kids or use real estate websites like Redfin or Zillow, you’ve probably seen the school ratings from GreatSchools, an organization that describes itself as “the leading national nonprofit empowering parents to unlock educational opportunities for their children.” My kids’ school is rated a “4”. That’s out of 10. When I was in school, 40 percent was not a grade that my parents or I would have been happy with. There would have been a fair amount of freaking out about a 4 out of 10. And yet my children, and all of the other 330 kids in that school, are learning, having fun, and occasionally misbehaving or letting off steam. They are being kids. The more I think about it, the more I wonder how a building full of people — actual kids, teachers, parents, and staff — can be described by a single number.

I am very happy with our school, even though it has some pretty significant challenges. It isn’t a “4” to me, or to most other parents I’ve talked to. I have friends at other nearby elementary schools with ratings of “3”, “4”, even “2” — they also love their schools. So why is our school’s GreatSchools rating not in alignment with my experience, and so many other people’s experience? As it turns out, these school ratings aren’t just inaccurate: they perpetuate the inequality that they aim to reduce, exacerbating segregation and resource hoarding in the process.

First, a little bit more about my experience. I knew our school was remarkable when we toured it. I saw a young girl put her arm around the shoulders of a classmate (who appeared to have significant special needs) and guide her carefully through the library. This act of care stuck with me, but mostly, I just saw lots of cute kids. Many were students of color, some girls wore hijabs (headscarves), and there was a wide range of disabilities and special needs. It was clear to me that this community was a better reflection of the world than a school that is white, privileged, and segregated. So, we left our more white, privileged, and segregated school — which, incidentally, has a GreatSchools rating of 7 — and moved our children to this school.

Our new, lower-rated school has provided exactly the kind of education my kids need. Truthfully, it has also provided the kind of education I need as a white, privileged parent. My older son, a reading fiend who’s considered an “advanced learner,” is thriving, especially socially. I won’t say the academics are as rigorous as before, but they’re also not as stressful. I have seen his anxiety drop and his social life develop in a very healthy and positive way — something I don’t think would have been possible at the whiter, much richer school he attended before. In our previous school, there was a clear majority from whose norms he desperately did not want to deviate. His drive to conform was strong. He cried in class often. And our platitudes to him about diversity held little weight or relevance to him there. Now he is one among many — many different races, different economic classes, different religions. It seems his anxiety-producing impulse to conform can’t find root.

The diversity of the school fosters rich conversations between my husband and me, and between us and our kids, about race, class, and difference. Why does a classmate wear a headscarf? What is her experience fasting for Ramadan? What is a Christian? What is an atheist? We’ve engaged with these issues as parents much more deeply than when we were lazily floating on the river of sameness at our old school. We are now “riding the rapids” of difference, which is sometimes scary, but also empowering — empowering because we’re learning and developing critical thinking skills rather than going along with the flow of what everyone else does.

My younger son, who is in kindergarten, just told me the other day that he actually likes school. He’s enjoying himself while learning to read, write, and interact with peers who look and act differently and have different abilities than he does. He gets a social education as much as an academic one. Most importantly, there are loving, dedicated, and hard-working teachers and staff at school every day telling all the students that they matter and that they can learn. These factors are very important to me, and a numerical rating system will never be able to tell me about them.

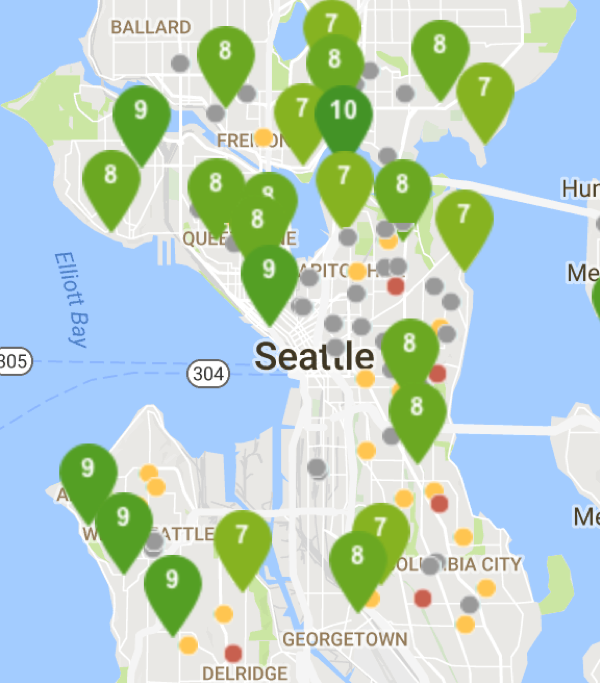

Now, let’s talk about the problem with GreatSchools. When you do a search for schools in a particular area on their website, you find that the “good” schools are marked with big green tear drops (let’s call them “Go Here! Drops”). The schools rated 7 or less are represented by little red or yellow circles (let’s call them “Stay Away! Circles”). Here is Seattle, where I live:

Parents who see those little yellow and red dots are bound to find them worrisome. The ever-present narrative is that you MUST send your kids to the good schools, and do whatever it takes to get them in. Or you send them to private school (which many do in Seattle). Why is this the narrative? Because that’s what everyone else says and does. Because we are asking and answering other people’s questions. But we need to be asking other (or at least more) questions — questions about the schools, about ourselves, and about the methods used by GreatSchools.

So what, exactly, is GreatSchools measuring? Mostly test scores, and therefore, socioeconomic status. In fact, Jack Schneider, a historian and researcher who studies schools, has written that factors schools can control usually explain only about 20 percent of a given student’s test scores: what really matters is a student’s socioeconomic status. Low-income students tend to score lower than high-income students, regardless of where they go to school. Much has been written about why, and there are multiple reasons. For one, researchers have found that poverty negatively impacts kids’ language environments. By contrast, middle- and upper-class parents are, from day one, cultivating their kids’ language and other skills, setting them up to stay in the middle or upper class.

Certainly, the more words you know, and the more your parents and your upbringing have cultivated you for educational success, the better your test scores will be. And it is these scores that can account for a significant portion of GreatSchools’ Summary Rating (47 percent of GreatSchools’s rating for a “representative example” elementary school, and a whopping 72 percent if you add in “Student Progress” on tests). This means that the GreatSchools rating system is basically telling you to find high socioeconomic students and avoid lower socioeconomic students (and English language learners, kids who qualify for special education services, and so on).

I can attest that the testing situation I’ve just described is true for my kids. Ours is a Title I school where 65 percent of students qualify for the free and reduced-price lunch program, and, significantly, upwards of 20 percent are homeless and 40 percent turn over (i.e. leave) every year. While many students at our school do not meet the standards for their grades, my kids test fine.

GreatSchools seems to be aware that there may be a problem with their methodology: in late 2017 they adjusted their ratings to include an equity component. GreatSchools say this equity rating measures “the performance level of disadvantaged students on state tests in comparison to the state average for all students, and . . . in-school performance gaps between disadvantaged students and other students”. This component accounts for about 28 percent of a sample elemantary school’s rating on GreatSchools’ site. (The weight of each rating component varies by state, district and even school, but the weights for each component can be found for each school at the top of its profile page.) Their website says: “We believe that every parent — regardless of where they live or how much money they make — needs reliable information in order to ensure their child is being served by their school.” They have many pictures of Black and Brown families on their site.

While they may sincerely wish to effect positive change, it’s worth noting that they appear to be funded by revenue from ads for private schools as well as funders like the Walton Family Foundation (a conservative philanthropic organization created by the owners of Walmart). This organization in particular has been hostile to public schools — hostile to the very idea that public schools are a common good that supports a robust, flexible, and tolerant democracy.

We also need to ask how useful these school ratings are to the Black and Brown families they picture on their website. The Go Here! Drops show up almost exclusively in majority-white neighborhoods where, in Seattle and cities like it, there is little or no affordable housing. (That school with the 10 on the map above is in a neighborhood where, as of this writing, there was nothing for sale below $1 million.) I also have to wonder how much revenue GreatSchools generates by licensing their ratings to Redfin and other real estate sites that target people who have the wealth to purchase a home in the first place. Those who can afford a home in a zone with a “good” school are not low-income or low-net-worth families. Even GreatSchools’s president, Matthew Nelson, says that the best way to know if a school is right for you is to visit it and talk to people in the community. So what purpose does that single-digit rating really serve, then?

These ratings don’t just oversimplify the relative quality of schools: there is evidence that they perpetuate segregation. The increasing income segregation our cities are experiencing is exacerbated by families with high incomes seeking good schools. Schools are about as segregated now as they were before Brown v. Board of Education. For poor and non-poor students, school segregation increased from 1991 to 2012 by 40 percent. Real estate segregation and school segregation have long been linked: government policies, redlining, and restrictive housing covenants created a lasting phenomenon. But now, we have an app with a rating system that does the job more efficiently than ever, even if the overt racial animus that originally caused segregation has lessened.

If school ratings, especially test-score focused ratings like those calculated by GreatSchools, are a problem, how are you supposed to pick a school? First, take the two-tour pledge: set foot inside at least two different schools. You wouldn’t buy a house without seeing a few in person, so why not take the same approach to your child’s education? When we were deciding on our current school, we toured schools and talked to teachers and parents. It didn’t take that much time, and walking around and seeing the actual people in the building ended up being the most important factor for us.

Second, remember that parents tend to repeat the dominant narratives about a particular school whether they are actually true or not. They will tell you a school is “good” or “bad” even if they’ve never visited it. I noticed this when talking to other parents. People who had never set foot in our old school called it “the private school of Seattle Public Schools,” probably because it was known to have high test scores and be populated by middle- and upper-class students. It was, in turn, other middle- and upper-class families who relayed this narrative. Researchers like Jennifer Jellison Holme have likewise found that families form their opinions about schools based on what other privileged parents say about them.

Finally, assess your values and your goals for your children. Like me, you probably want a lot more for your kids than high test scores. Like me, you might worry that not being around high-achieving peers, or occasionally having screen time at school (gasp!) could hurt their prospects as adults in a competitive world. The difficult truth, however, is that if your kids are socioeconomically advantaged enough, they are likely to get high test scores no matter which school they end up in. I believe that the dismantling of systems of segregation and racism is worth the anxiety we may feel about putting our children in schools with low test scores and GreatSchools ratings.

As you consider these various issues, you may want to read about how parenting to advantage your kids can actually cause harm. If it is important to you that the kids in your school be like your kid, and the families be like yours, ask yourself why — don’t allow racist stereotypes to go unchallenged. Talk to some families who have chosen integrated schools, read about a Seattle parent’s choice to attend a mostly Black school, and read this post on sending your privileged kids to a “low-performing” school.

For more about integration and its positive effects, read the work of Nikole Hannah Jones and this essay on how diverse schools benefit all students. Finally, never forget that integration is not about benefiting the privileged kids, or letting them see Black and Brown children in the halls on their way to their segregated advanced placement classrooms. It’s about deeper and equitable learning for all students.

The decision may not be easy. We certainly spent a lot of time on ours. But I do know that a school can’t be reduced to a number — my kids are not a number, and neither is any other child.

(Note: I removed a reference to one study that showed that by the age of four, kids from low-income families may have 32 million fewer words directed to them than their middle- and upper-class peers. I did so because of some problems with the methodology of the study, and concerns that focusing on factors like word gaps may blame families for their own poverty rather than the racism, classism, and ableism rapant in this country.)