The battle over the future of bitcoin

Billed as the future of democratized, digital money, the currency is now at the center of a conflict over how to develop technologies behind the system

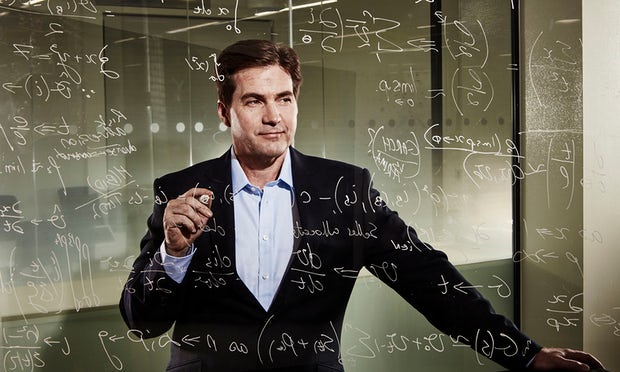

The bitcoin world this week learned its absentee father might be Craig Wright, an Australian entrepreneur with nice suits and well-combed hair who claims he invented the digital currency.

Wright’s appearance complicates an already vicious custody battle. His claimed brainchild bitcoin – long billed as the future of democratized, digital money – is at the center of an ideological conflict over how to develop the technologies behind the system.

Bitcoin is a paperless, bank-less, state-less currency that allows people to pay directly for goods and services. The coins themselves are made by computers solving a set of complex math problems, and people who use their computers to make coins and record transactions are called miners.

The value of a bitcoin has fluctuated wildly since 2009 but now hovers between $400 and $450. To spend it, users buy bitcoin and transact using a third-party app such as Coinbase. Rather than a central authority validating transactions, all transfers are recorded on a public ledger. It can be used to pay for coffee, dinner or software from online stores as well as some real-world shops.

Fans of bitcoin say the system, which tends to be a pet project of encryption wonks, could eventually rival Visa. Yet transactions are already taking longer to clear – sometimes more than 40 minutes, which is a long time if you’re in a grocery store waiting for your payment to process. And without agreement on how to resolve the problems, it might soon become hard for anyone to use the service. So what’s causing the problem?

Nerds are calling each other “nerds” behind each other’s backs. It’s a “big communications breakdown”, according to Eric Lombrozo, chief technology officer of the bitcoin transaction firm Ciphrex. On the other side of the fence, Peter Smith, whose firm Blockchain tries to help people pay with bitcoin at places like local coffee shops, says “religion does perhaps explain it well”.

It’s unclear if Wright declaring himself to be bitcoin’s mythical creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, will help resolve that process. Wright is on the side of people like Blockchain’s Smith, a former financial services consultant whose firm raised more than $30m in venture capital, has offices in London and New York, and counts Virgin’s Sir Richard Branson as an investor.

Advertisement

Smith won’t give his age, though his biography suggests he is in his early or mid-30s. He’s youthful, and his voice occasionally cracks when explaining the intricacies of virtual currency. On his Twitter page he describes himself as a “capitalist, explorer and coder”.

Naturally, Smith wants bitcoin to grow quickly – preferably very quickly, handling lots of transactions at the same time so it’s faster and more convenient for users to spend money, and so that his investors make a bigger, faster return on their investment.

Along with other bitcoin companies, Smith is trying to improve the process to handle more consecutive transactions to reduce delays and boost volume. This isn’t as simple as flipping a switch. Unlike Visa, bitcoin doesn’t have a central clearinghouse to process all transactions. Instead, each purchase and transfer is verified by one of thousands of computers on a volunteer network and bundled into a digital “block”. Each block of transactions is then recorded on a central ledger called the blockchain – the inspiration for the name of Smith’s firm.

https://cdn.theguardian.tv/mainwebsite/2014/04/30/140417Bitcoinmadesimple-16x9.mp4

Bitcoin’s mainstream popularity has grown in fits and starts in recent years. For all its technological brilliance, there still isn’t an easy way to use it at major stores, and spending a coin can appear to be more trouble than it’s worth. For consumers, paying a merchant in person with bitcoin is similar to using PayPal or Venmo. They would need to open an app, pull up the store owner’s bitcoin address and than transfer the funds, which can take several minutes to clear.

Big blocks, little blocks

Smith, Wright and some other key bitcoin developers want the blocks to be larger so more transactions can clear at the same time. Their argument is both financial and philosophical. Sure, they could make more money, but bitcoin could also become more democratic and less a pet currency of techies.

To them, this is the whole point of the bitcoin project. On command, Smith can quote bitcoin’s originating documents like a supreme court justice combing over America’s founders’ early writings. An early email sent by Satoshi – or maybe Wright – spoke of Bitcoin becoming larger than Visa and relying on massive blocks.

But for the blocks to get bigger, the people who run the computers that make blocks – so-called Bitcoin “miners” – need to switch to a different software designed by the advocates of bigger blocks. And a lot of the miners aren’t prepared to switch, partly because some key Bitcoin developers have convinced miners that blocks for now should stay small.

If blocks become increasingly larger, miners will need more computing power to produce blocks, which means they’ll need more money for more computers. Eventually, they warn, only professional mining operations will be able to produce blocks of transactions.

This all cuts against one of the key premises of bitcoin – that the currency is decentralized and not influenced or controlled by a central bank or corporation like Visa. If bitcoin blocks get too large, it could become a system controlled by a few powerful groups of miners, the small blockers warn.

Yet there are also business interests at play. In 2014, before bitcoin’s current identity crisis, bitcoin developer Gregory Maxwell and several encryption enthusiasts co-founded Blockstream, a bitcoin startup that tries to develop new ways to use the currency’s main technology, the blockchain. Banks and insurance companies, for instance, could automatically enforce contracts through their own, walled-off blockchains. They could also help add more capacity to the broader bitcoin network by adding more “side chains” to the system to help the main chain handle more blocks.

In short, Maxwell and his team have a business interest in blocks staying small, because more people would need side chains. To Smith, the big-block proponent, Blockstream’s position “does seem like a conflict of interest”.

Maxwell and other Blockstream employees didn’t respond to interview requests. Rather, Blockstream president Adam Back referred the Guardian to Lombrozo, the co-founder of Ciphrex and a small-block proponent.Lombrozo countered that Blockstream is trying to improve the foundation of bitcoin in a more gradual and secure way.

Rather, he said consumer-facing bitcoin companies that help people spend the currency on everyday goods in popular stores are overeager to grow the currency too quickly to meet revenue targets.

Lombrozo said the group of developers in favor of keeping the small-block system want bitcoin’s foundation to improve before trying to grow it. “Everyone would like to see this expand and become very global,” he said.

Bitcoin, meanwhile, may have bigger problems. After White on Monday announced that he was the real Satoshi, security researchers and encryption experts began to question his public proof of his secret identity.