Descartes and Certainty

Why is the Cogito the only ground for certainty?

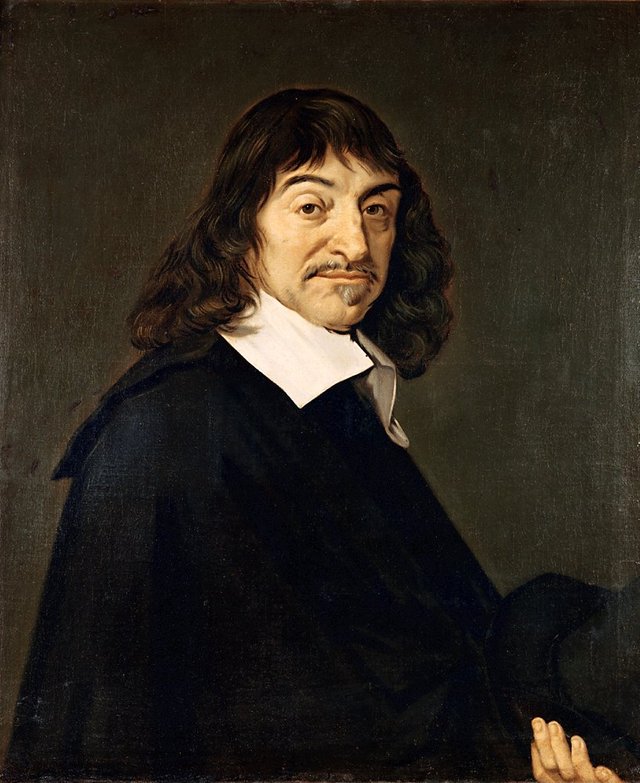

René Descartes, a 17th century philosopher and scientist, was primarily concerned with the notion of false beliefs. In his Discourse on Method, he plainly frames the dilemma that “diversity of our opinions does not arise from the fact that some people are are more reasonable than others, but solely from the fact that we lead our thoughts along different paths and do not take the same things into consideration” (1). For Descartes, the idea that different people who all seem to be thinking rationally can achieve different conclusions was a problem as it could threaten to mislead those pursuing science and no one would know that they are being mislead. What’s more, he feared that the uncertainty inherent in philosophy could threaten to undermine the development of sciences. “Concerning philosophy I shall say that, seeing that it has been cultivated for many centuries by the most excellent minds that have ever lived and that, there is still nothing in it about which there is not some dispute, and consequently nothing that is not doubtful … Then, as for the other sciences, I judged that, insofar as they borrow their principles from philosophy, one could not have built anything upon such unstable foundations” (5). To state it plainly, philosophy is not stable so any sciences grounded in philosophy have the capacity to become compromised by false beliefs. This fear, coupled with his fixation on the foundational principles of what we believe, provides the catalyst for his meditations, and later gives rise to the Cogito argument, which Descartes argues is the only way to avoid the potential for false beliefs.

In his initial efforts to establish a foundation that was“firm and lasting in the sciences,” Descartes begins the first meditation by subjecting everything he knows to radical doubt (59). By beginning with only the things which cannot be doubted, he cannot produce beliefs which are built upon false foundations. In order to cast aside any deeply held, yet false notions, he subjected everything he believed to the same level to scrutiny that one would give towards something they believe to be “patently false” (59). This radical first step provides the basis for the Cogito argument. He first levels his doubt at his senses. Based on the fact that dreams exist, he makes the case that our senses can be deceived, and therefore cannot be trusted. For Descartes, since we are capable of dreaming and our senses feel real in our dreams, there is a chance that what we believe to be our waking hours could a dream or a dream-like state. Based on this realization, all sciences which are rooted in perception are capable of being doubted. Math, on the other hand, cannot because “whether I am awake or asleep, two plus two make five, and a square does not have more than four sides” (61). By the end of this meditation, Descartes cannot say with certainty that all but one of his beliefs can be doubted and thus rejected. The only thing he can always be certain about is that when he is doubting, he is doubting. This is the fundamental principle of his Cogito argument.

Meditation two resumes the following day where Descartes thinks upon the nature of doubt, and as he cannot doubt the fact that he his doubting, he develops a new step. If he cannot doubt that he doubts, and doubting is thinking, then he cannot doubt that he thinks. This in turn presented the challenge of having to explain where the thoughts come from and who or what he is. For Descartes, there could be two possible places from where thoughts originate. Either ideas came from within himself, or “some God … who instills these very thoughts in me” (64). In other words, his ideas are either his own or are planted within him from somewhere else. Neither option cannot be doubted, but the conclusions for both are identical: when he thinks he can be certain that he exists. If his ideas come from within himself, then he must exist. If ideas come from an external source and are given to him, then he must likewise exist. Since both possible origins could be true and both share the same conclusion, while he cannot be sure of the validity of either origin, he can be unshaken in his belief of the conclusion. The next step in his second meditation is explaining what he is. As he can be sure of his existence only when he is thinking, he can undoubtedly state that he is a thing that thinks. He cannot state affirmatively that he is anything more than that, because he cannot be sure that what he believes, or does, or perceives is absolutely certain.

Throughout his meditations, Descartes demonstrates the application of Cogito as a means of ensuring certainty. By accepting only that which cannot be doubted, he begins with foundational principles which are unshakeable. With the core principles, he applies careful reasoning do derive additional and equally unshakeable permutations of the core principles. Through gradual and methodical application of the unshakable beliefs, Descartes seeks to restore belief in all things which cannot be refuted so as to ensure that future developments in science, mathematics, and philosophy are not betrayed by underlying falsehoods. The two ways that Cogito is guaranteed to produce certain results are the application of doubt and the methodology by which logical progressions are attained.

Without radical doubt, Cogito would not produce certainty. In fact, this is the fundamental reason why Descartes believes Cogito is the only way to be certain. The reasoning is fairly simple. All that can be doubted has the possibility to be false. Anything which under no circumstances can be doubted must be objectively true. The conclusion that he exists based on the unshakeable fact that he has thoughts is an example of this principle at work. It is important to note that his radical doubt does not mean that things that can be doubted are necessarily false, but merely they cannot be accepted as irrefutably true. Taking the example of his existence again, either origin of thoughts is true, and in fact one must me true. Descartes doesn’t know which of the two is accurate, but as both can be doubted, both are rejected. Part of what makes this extreme doubt so effective at eliminating the possibilities for false beliefs is the level of restriction. In the above case, he is knowingly rejecting at least one true statement, but undeniability is a fundamental property of everything that he will accept. This can likewise be demonstrated by his rejection of corporeal form. He likens physical form to a ball of wax which appears solid and can be judged as having a distinct shape, feel, and smell. Once heated, the wax loses its recognisable characteristics. “Does the same wax still remain” (67)? Either it remains the same wax and the loss of its features does not change the fact that it is the same wax, or the molten wax is different than the original wax in ball form. Applying radical doubt, Descartes arrives at the idea that physical form and features cannot be believed unshakably. While intuition would lead us to believe that what is around us is both real and what we think it is, there is some doubt that can be leveled at these beliefs. Descartes’ doubt is much less concerned with the possibility of rejecting true things than accidentally accepting false things. Rejecting true things will never lead one down a path with a false sense of certainty while accepting false things can.

The next reason that Cogito is certain in its conclusions is the way steps are taken. Much like algebra, Descartes begins with an unshakeable belief or set of beliefs, and used logical unshakeable manipulations of the information, the conclusions drawn are equally unshakeable. An example of this these manipulations would be from meditation two where he tries to discern what type of thing he is. He has already derived the facts that he exists and that he can think, and he is unshakeable in his belief that two indubitable things can be conjoined to produce a likewise unquestionable conclusion. He used this principle to combine the two facts to produce the newly derived truth that he is “a thinking thing” (65).

Anything that can be doubted has the potential to be false. Combining true things with true things can only produce true things. These are the principles of Cogito. Without unshakable beliefs in every step of a logical progression, from the most fundamental, to the highest order, there is no objective proof that what is believed is absolutely true. That is to say that anything that exists in absence of unshakeable belief, can be doubted and thus can never be truly certain. Only by ensuring every step along the way cannot be questioned, can a conclusion be reached with absolute certainty.

Works Cited:

Descartes, Rene. Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy, Hackett

Publishing Company, Inc., 1999. ProQuest Ebook Central,

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/jhu/detail.action?docID=583972.

Beautifully and cogently written. Indeed uncertainty is necessary even for the development of science and until every uncertainty is checked and crossed, we cannot be absolutely certain.

thank you very much