Meet the Women Who Broke Enemy Codes in World War II

New York Times best-selling author and award-winning writer Liza Mundy and Montclair University associate professor Jessica Restaino highlighted the women who deciphered Japanese and German codes during World War II and were profiled in Mundy’s book, Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II, at the Montclair Public Library in New Jersey on May 29, 2018.

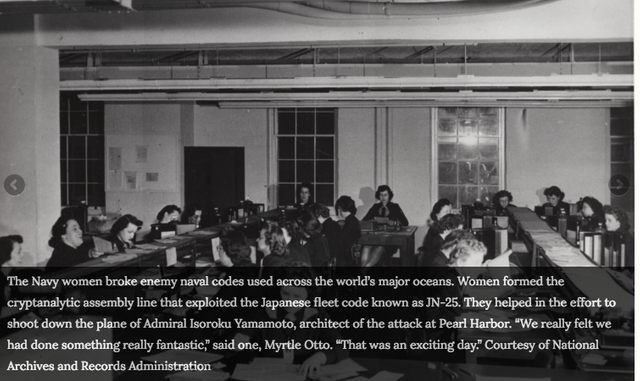

During World War II, the U.S. Navy and U.S. Army recruited more than 10,000 women—over half of the code breaking workforce—from Goucher College, in Baltimore, Maryland (Dean Dorothy Stimson was the U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson’s cousin), the Seven Sister schools, teachers colleges, as well as school teachers to break the Japanese code system known as 2468, one of the most important code breaking triumphs of World War II.

These women broke the encrypted radio messages that traveled between the Japanese ships its army commandeered to deliver food, fuel, oil, reinforcement troops and spare airplane parts around the Pacific. Once these codes were deciphered they were given to the U.S. submarine commanders who could identify the Japanese troops’ locations.

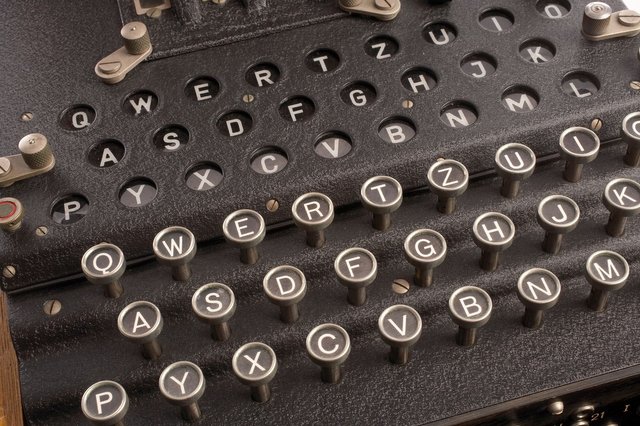

They also created “dummy traffic” or fictitious communications that would persuade the Germans that the U.S. troops planned to invade Pas de Calais, France instead of Normandy, and decoded messages generated by Enigma machines used by the Germans.

“I think it's important to remember that when we went into World War II after the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor, there was no foreordained conclusion that we're going to win. We didn't know at the time that we were going to win and it felt very much that we could lose. All of Europe was practically occupied by the Germans. The fascist menace was very real. Japan was a very feared adversary and we didn't have any intelligence agencies. I live in Washington D.C. We have 17 intelligence agencies now. We have intelligence agencies that exist to oversee other intelligence agencies, but we didn't have anything like that and all of a sudden we've entered this global total war and then men are departing daily and we don't know,” said Mundy, who serves as a senior fellow at New America, a non-partisan think tank.

She continued:

“There's armies and navies strung out all over the world and we don't know where the enemy is. We know we've been attacked. We've been surprised. So, all of a sudden we had to teach ourselves how to do intelligence and we will start the OSS, which is the forerunner of the CIA, but that takes a while to set-up spy networks. So we have to start immediately in real-time reading these encrypted radio messages that are controlling the U-boat movements; that are controlling the movements of the Japanese Navy; the supply ships that supply the Japanese Army, and we have to do it urgently and immediately. There's no training period. There's no time to get up to speed, and the women, who flood into Washington to do this work. Some of them have received no instructions.”

Image from Mundy's website. Credit: National Archives and Records Administration

The women, who were chosen because of their advanced math and language skills and were “loyal and and rule-observing and (could) tolerate failure and tolerate frustration, who have persistence and grit,” signed a secrecy oath in which they agreed to the penalty for speaking about their code breaking work would be death.

“So they were all told that they will be shot if they talked about what they did. They were told that if anybody asks them what they did at these giant top secret code breaking compounds in Washington D.C., they were to say that they were secretaries, that they filled inkwells, they emptied baskets, they sharpened pencils. And because they were women, people believed that the work they were doing had to be trivial and secondary and unimportant,” Mundy explained.

She also said if the Germans and Japanese discovered their code breaking operations, they would change their code systems, destroying their work. When World War II ended, their roles remained secret because there would be more code breaking operations implemented as the U.S. went into the Cold War with Russia, East Germany and China.

Mundy also shared that these women kept their code breaking roles secret because no one told them this information was declassified around the 1990s.

Dot Bruce (née Braden), one of Mundy’s central characters, grew up in Lynchburg, Virginia, the oldest daughter in a family of four. Her mother, who was separated from her father, wanted a better life for her daughter, which meant obtaining a college education (Mom was a secretary in a Lynchburg uniform factory). So Bruce went to Randolph Macon Women's Academy, a Lynchburg women's college.

She accepted a job teaching school in Chatham, Virginia in 1942 because that was the only position open to her. While she taught school, she felt overwhelmed by her teaching load the first year of the war because all the male teachers were gone. During this time, her college boyfriend, George, asked her to marry him. She didn’t want to get married directly after school but she also didn’t want to upset George who was at a training camp in California, so she kept the engagement ring he mailed to her. Sometimes she wore it. Sometimes she didn’t.

Bruce signed up for a job with the U.S. War Department at a Lynchburg hotel unaware that the U.S. Army was recruiting code breakers. She thought it could be opportunity for her to become independent and travel to Washington, D.C. “She had never been to Washington because it was three hours away, because she went through the Depression. So it's a chance to be something other than a school teacher, to make almost twice as much as what she made teaching school. They get $900 a year teaching school, you would make over $1,600 a year as a code breaker,” said Mundy.

An Enigma machine.

Louise Pearsall, who tested the Enigma machine key settings, grew up in Elgin, Illinois. Her love of math and statistics inspired her to attend college to become an insurance actuary, but her father stopped paying her tuition after he realized her education would fail to secure Pearsall an actuary job. So she traveled to California and enlisted in the U.S. Navy WAVES or Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service.

“But she was so good at math and she ended up very highly placed in the Enigma unit, figuring out these algorithms, basically along with men who had been professors at MIT and Yale and places like that doing this great work. And she was never able to tell her father that she put his tuition to work to do this incredible life-saving work,” Mundy shared. “And after the war she missed it more than almost anybody.”

What Happened to the Women Code Breakers When World War II Ended?

“They were all for the most part encouraged to leave after the war,” Mundy explained. “You know, told to leave after the war. They were denied in many cases, opportunities. The Navy women were veterans and they were in time for the GI Bill.”

Some of the women attended graduate school, but some were shut out of certain graduate schools. Bruce married the man she loved, an Army officer, and they had a happy marriage and great children. “But I will say that she has now said to her children—she's almost 98 — that this publication (Code Girls) was the most important thing that had ever happened to her. And so I would say even somebody like Dot, who had a good life, still felt like she had been denied recognition and credit for what she did.”

The U.S. Army kept its code breaking force, 7,000 women, as civilians, which meant there wasn’t as much of a hierarchy. “If a 22 year-old turned out to be really hot shot, good at it she would be in charge of the unit,” said Mundy.

After the war, a group of Navy enlisted WAVES started a chain or round robin letter that included their daily activities, which lasted 75 years.

Where Were the Female African-American Code Breakers?

The U.S. Army was segregated during World War II, so its female African-American code breaking unit was segregated. School teachers who were recruited as code breakers deciphered encrypted messages in the corporate world.

“So just as Amazon and all of our banks and all of our financial transactions are encrypted, banks and companies were encrypting their cables as well and they were working the private sector to see who was doing business with Hitler or who was doing business with Mitsubishi,” Mundy shared.

The U.S. Navy code breaking unit was all white and didn’t accept African-American WAVES.

Why Should We Care About These Women?

“I mean this was early cybersecurity and cyber intelligence, just as the women who were designing the ENIAC computer for the Army and Grace Hopper designing the Mark computer.

"So much of our STEM innovation came out of World War II and because the men were unavailable and they were fighting, a lot of the STEM innovation was done by women. And so to argue that women are not biologically suited for the tech sector when in fact they helped found it,” stated Mundy.