CANADA'S FIRST FACE TRANSPLANT

MONTREAL — It took 12 hours to remove the face, four surgeons working from early morning into the night, cutting through skin, muscle, blood vessels, nerves and bones, until it was lifted from the man’s skull.

It was a beautiful face. The flesh smooth and plump, the mouth and lips generous and full. It was still attached by two arteries and three veins to the donor’s neck. His heart was still beating strong, his body warm to the touch. His skin flushed pink with blood.

But when the surgeons cut and clamped the last five vessels, freeing the face entirely from the brain-dead organ donor’s body, it instantly began to turn white as his life drained from it.

Dr. Daniel Borsuk cradled the face in his cupped palms, carefully washed away the blood and injected the arteries and veins with a preservation fluid. Without a blood supply it would survive only two to three hours.

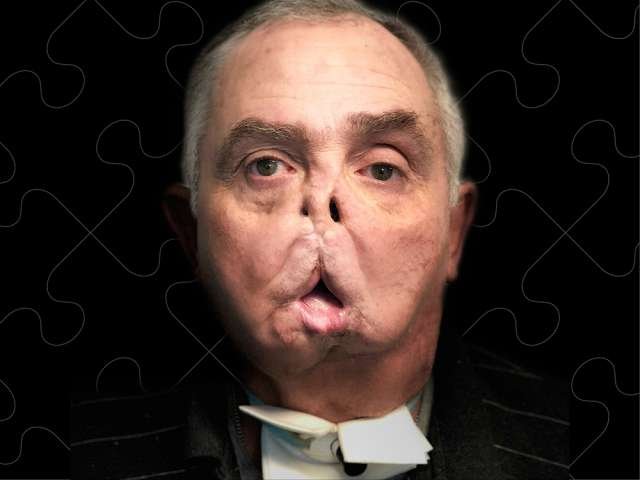

In the next room, Maurice Desjardins was almost ready. His old face, the mutilated one, was gone, disassembled over 17 hours by a second team of surgeons. Only his eyes, upper eyelids and forehead remained.

On the rare occasions Desjardins left his rural home outside Gatineau, Que., he wore surgical masks. He lost his roofing business. He had lost his former self by the time he was sent to Borsuk, a plastic surgeon in Montreal adoring patients refer to as “un magicien du visage.” The doctor told him he had only one real option left, something never before attempted in Canada: A face transplant.

It took five years of planning, nine surgeons, five anaesthesiologists and more than 100 other medical, nursing, support and technical staff. But when Borsuk finally carried the donor’s face to that second operating room and placed it over Desjardins’ skull, it snapped into place perfectly, like a puzzle piece.

Borsuk experienced an almost religious calling to plastic surgery. He was a first year MBA student at McGill University when Dr. Chen Lee, the then newly appointed head of plastic surgery, called the business school for help. Lee was looking for volunteers to help find the delays, the bottlenecks to rapid care for people who needed accidentally amputated body parts reattached.

One day Lee called Borsuk. “Dan, come to the operating room,’” he told him. A 14-year-old had amputated his arm in a wood chipper. Lee wanted the young business student to see what microsurgical replant surgery could do. Borsuk arrived at the Montreal General in his suit and tie. He was taken into the operating room, “and there’s an arm and a kid and it’s the most incredible thing. I was standing there in shock. I didn’t realize you could literally attach an arm and the nerves and the tendons. It was so complex and wild. It was like Star Wars.”

“This is what I want to do,” he thought. “I want to do this.”

Four months later, Borsuk returned home to Montreal, where he was named head of plastic surgery at Sainte Justine. He divides his time between the children’s hospital and Maisonneuve-Rosemont, both University of Montreal teaching hospitals. Borsuk started building a practice, but the university was interested in building something more: Its own program for vascularized composite allotransplantation —transplants that involve not just a single organ, but muscle, nerves, bone and skin. Transplants like hands and arms. Transplants like faces.

In the United States, the military has supplied millions of dollars in grants to surgical masterminds with the goal of helping Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans with faces demolished by crude homemade bombs. In Canada, no one was handing out that kind of money. To help offset the cost, to make face transplants more palatable to the public, Borsuk started looking for outside support.

“Once I had that, I approached the hospital, saying, ‘I’m coming already with some support,’” Borsuk said. “I didn’t want to take surgery away from someone who needs cancer surgery; I wanted to know I was not taxing the system.”

He then approached Transplant Quebec. Their approval was essential. “I’m going to tell you a little about myself and I’m going to show you some patients that I really have no options for,” Borsuk told them.

One of the photos was of Desjardins.

Borsuk ran through the case: Gunshot injury to the face. Permanent tracheostomy. No sense of smell through what was left of the nose. Tongue buried behind scar tissue. When Borsuk first met Desjardins and asked, “If I were a magician and could do anything in the world for you, what would you want?” Desjardins said he just wanted to lead a normal life. He wanted to walk outside with his granddaughter without hiding behind a mask. But he didn’t want any more painful reconstructions. His leg and heel still ached where surgeons pulled bone the last time they tried to build him a new mandible.

Borsuk told Transplant Quebec about his experience in Baltimore: He said he wanted Montreal — the first Canadian centre to perform a successful kidney transplant between identical twin sisters in 1958, the first place in Canada to perform a human heart transplant in 1968, the first in Canada to do a liver transplant — to be the first to give a man a new face.

Beaulieu also needed reassurance that Borsuk wouldn’t risk other organs while taking the face. Borsuk agreed that if the donor’s blood pressure began to plummet, if they began losing him in any way, he would stop until the other organs could be taken.

Transplant Quebec secured the necessary ethical and legal approval. Donor coordinators decided they should only approach families if they had already consented to give a loved one’s kidney, liver or other critical organ: You are so generous. There also happens to be this research protocol where we are doing a face transplant. Special legal consent forms were drawn up that state, in part, that the family member has “no knowledge of any hesitancy on the donor’s part concerning the donation I am about to make on his/her behalf.”

Borsuk started assembling his team: plastic surgeons, ear-nose-and-throat specialists, anaesthesiologists, kidney experts, microbiologists, physiotherapists and nurses. “I knew who my people would be.”

Dr. Hélène St. Jacques has worked with people receiving new organs. A face — not an invisible internal body part — adds an entirely new emotional dimension. When Borsuk first approached her about Desjardins, she wondered: “Am I the right person?”

“He was severely disfigured,” St. Jacques said. “He had to wipe his mouth constantly when he was speaking, and he was difficult to understand.”

“We had to discuss — and it was very theoretical — the potential identity change,” she said. “But he was a mature person who gave a very frank account of what happened. And he was very, very isolated. He lives in a very small village. People would stare. They would make comments. Adults. Something you teach children not to do.”

“Maurice said, ‘I have nothing to lose.’”

Borsuk and his team of surgeons began rehearsing in the basement cadaver lab. They propped the cadaver heads up on steel tables and separated into two teams — one for the donor, the other the recipient — and practiced, over and over: Should they get rid of this gland, or keep it? Is it easier to find the nerve that way, or harder? They worked through every possible maneuver and complication and mapped out their results. The day of the transplant, their notes filled white billboards in the operating room.

That day came two years after they started practising in earnest, and two weeks after their last run-through on the cadavers. One morning in early May, Borsuk’s cellphone rang. Bernard Tremblay, an organ donor coordinator with Transplant Quebec, was on the other end. He was calling from a small, nearby hospital. There was a brain-dead man in the ICU whose family had consented to donate his organs. A white male, the same blood group as Desjardins, good teeth, no scars on the head or neck, no signs of previous trauma to the head or neck and who seemed to have similar colorization.

Borsuk’s heart skipped a beat. “What are you saying?” he asked Tremblay. “I think you should come and evaluate the patient,” Tremblay told him.

“Everything is fitting, like it’s Maurice.”

The visit lasted three minutes. Borsuk left the ICU and called Tremblay. “It’s a perfect match,” he said. Tremblay said he would approach the family. He didn’t try to oversell the transplant. He didn’t push anyone’s agenda. He remained neutral. “I meet these families at the worst time in their lives,” he said. “They’ve just lost somebody and I will never have the time to fully know them. I want what they want.”

Tremblay explained the research protocol. He explained the process. The family told him that if it meant potentially helping someone else they were willing to let them take the face, too.

Tremblay left the room and called Borsuk. “We have consent.”

Borsuk summoned his team.

While the donor was transferred to Maisonneuve-Rosement Hospital, one of the people Borsuk called was Virginie Bachand. A special effects make-up artist who normally works on television and film, he had hired her to create a lifelike silicone mask for the donor.

Borsuk didn’t want him leaving the operating room without a face.

She was 40 weeks pregnant and due to give birth when Borsuk had called to say the transplant was on. She almost fainted.

But she was determined to see it through.

“Let me speak to my obstetrician friends here so that if, God forbid, you come in and do the mask and go into labour we can deliver the baby here,” Borsuk told her.

At 6 a.m. the next day, Borsuk and ear-nose-and-throat surgeon Dr. Tareck Ayad performed a tracheostomy on the donor, and wired his jaws together. They couldn’t remove the face if it was still attached by a tube in his throat to a ventilator. They made CT scans of his head and sent the images to a team in Michigan to create a virtual surgical plan, allowing the team to practice one last time before surgery.

When Bachand walked into the ICU several hours later, she would have sworn that, if not for the breathing machine and beeping monitors, the donor was sleeping. She remembers thinking how handsome he looked. She made two impressions of his face, gently spreading silicone paste on his skin. She bent down and whispered close to his ear, “I’m sorry. This will feel a bit gluey and sticky.” They told her he was clinically dead, that he couldn’t hear her. “But I told myself that some part of him heard me, somewhere.”

Meanwhile, Desjardins had arrived from Gatineau so they could start the immune suppressant drugs.

At 4 a.m. the next morning, Desjardins was ready to be wheeled into the OR. Among the surgical teams was Dr. André Chollet, chief of plastic surgery at the University of Montreal. “Maurice, this is a new beginning,” he told him. “You are starting a new life.” Desjardins’ wife looked scared. She leaned over the stretcher, squeezing his hand. “Don’t leave me,” she told her husband. “You are going to get out of this surgery.”

The doctors started on Desjardins. It would take longer to remove his face, to clean things up, because of the multiple reconstructions. They would have to work through thick scar tissue and all the old screws and plates. And Desjardins had to be ready when the donor face came off, because in a perfect world, you want the donor face to have the least amount of ischemia time, the least amount of time there is no blood flowing through the face.

The surgeons made the first incision from Desjardins’ lower eyelids, across the bridge of his nose through the temple region, then around his ears and down to the bottom of his neck. They didn’t want to take his upper eyelids or forehead. Desjardins has almost no vision left in his right eye; any manipulation around the left eye could have cost him more sight, and Borsuk knew if he could get a perfect colour match there was no need to take off the forehead.

The plan was to start with the vessels in the donor’s neck. “We go through skin, we go through muscle to find the veins, the jugular veins and the carotid arteries,” said Chollet. At least one artery and one vein would be needed to keep the face alive.

Next, they followed the arteries to the tree-like branch of nerves that animate the face and activate the muscles that make us smile, talk, eat and drink. As they went, they stimulated the nerves with an electrical current, watching to make sure they were saving the right ones for normal movement.

The surgeons took turns. Dissecting, then assisting. Dissecting, then assisting. Everyone focused, concentrating on minimizing the bleeding.

“So once the vessels on both sides are dissected, the nerves on both sides cut and dissected, the pillars of the bone cut, Dan (Borsuk) cracks the face off the skull,” Chollet said. It came off as one piece. All the bones of the upper face, the maxilla, the entire mid-face and jaw, with the attached muscles and nerves and tissue beneath. It was 11.15 p.m.

The room went silent. “There must have been 20, 30 people in the room. And there was dead silence,” Borsuk said.

For Tremblay, for a moment, it didn’t seem real somehow. Plastic surgeons raise free flaps all the time — skin and vessels and fat from a belly to bring it to a missing breast. “You’ve never raised a free flap so important and here it is, and it’s an entire face, the bone, the nose, the jaws, the teeth,” Tremblay said. “You feel like you’re in a movie and it’s not really happening. But then you have to say, ‘Okay. This is it. We’re on a time frame. Let’s keep moving.’”

The team fixed plates on the bones of the donor’s face, plates based on a 3D replica of Desjardins’ skull without a face. At 12:10 a.m., the final vessels were clamped. Borsuk and Chollet moved to the next room. They placed the donor face on a table draped in blue surgical cloth. The face was white, its lips blue. Desjardins’ face was set beside it. They took photographs. Two faces without eyes. Old next to new.

At 2 a.m. they removed the clamps from the artery on the right side of his face. His lips and face began pinking up. Blood flow was coming in. The room erupted into applause. Dental surgeon Dr. Jean Poirier moved in to help align the jaws and make sure the teeth fit properly. Surgeons began working to stitch the sensory nerves together. But by now, there was no more need to rush.

The face was alive.

He was eased out of his drug-induced coma slowly, softly, like landing a plane, to reduce any agitation or delirium. He was alone in his room with Borsuk, Chollet and Tremblay, his wife waiting outside the door, when Borsuk set a mirror down on the hospital bed.

When Desjardins raised it, and turned it towards his face he stared at his reflection like a child. He gingerly touched his nose, and his chin. He pulled his bottom lip down to see the teeth. “And then he looked at me and he grabbed me and pulled me in and wouldn’t let go,” Borsuk said. “It was one of the most poignant moments of my life.

“I have high hopes he’ll be able to close his lips together,” Borsuk said. “It’s a question of time. We can’t rush these things. But does he like his face? Oh my god, he loves it. Yeah, he’s enjoying his face right now.”

At 65, Desjardins is the oldest recipient of a face transplant. He doesn’t look the way he did before the bullet nearly obliterated the lower half of his face, or the donor, but like a different man, a blend, a melding of the two. He wears a goatee now, his donor’s beard, the grey streaks and flecks of brown an uncanny match to his own eyebrows. The beard started growing the day after the transplant. Borsuk shaved his cheeks while Desjardins was still in deep anaesthesia in the ICU.

Since then, transplants have taken place in Turkey, China, Spain, Belgium and Poland. In the U.S., the “miraculous” surgeries have been performed on a Vermont woman whose husband doused her with industrial strength lye, a volunteer Mississippi firefighter whose respiratory mask melted into his face when a burning ceiling collapsed on him, a Connecticut woman mauled by her friend’s pet chimpanzee. The September issue of National Geographic chronicles the youngest recipient of a face transplant, 21-year-old Katie Stubblefield.

Face transplants cost an estimated $350,000 U.S., not counting the cost of a lifetime supply of anti-rejection drugs or follow-up revisions. That’s equal to about half a dozen reconstructions, surgeries that can leave faces patched together like quilts, with grafts and flaps of skin that often end up looking distorted or immobile. Mask-like. But the risks remain significant. It is complex, radical surgery, and the consequences, if things go wrong, are horrific: Death in about 16 per cent of cases, or if the vessels clot, cutting off blood flow, it can mean the loss of the entire graft, leaving the patient worse off than before, with no face, no bone. Just an open cavity. Doctors could take flesh and muscle from the patient’s own body and patch over the exposed face, until another donor could be found, “but that’s almost not viable,” Chollet said. “You would have a big blob of tissue in your face. No mouth, no nose, a feeding tube in your stomach, a trachea in your neck to breathe.”

In April, French surgeon Dr. Laurent Lantieri became the first to perform a second face transplant on the same patient, a Paris bookseller named Jérome Hamon. Lantieri first gave Hamon a new face in 2010, the world’s first full facial transplant, but last year the transplant began to shrink and harden. It became harder for Hamon to open his mouth and his eyelids. By November, the tissue began turning black from necrosis. The face was dying. Lantieri had no choice but to remove the entire donor face, leaving Hamon with no ears, no eyelids, no nose, and no lips. He lived in isolation in hospital for two months, unable to speak, see, eat or hear, a sensory deprivation nightmare. He meditated to stay sane.

Today, Hamon has some slight movement in his face. “I cannot say he is doing well,” Lantieri said. “I’m just saying he has survived from all these things and we hope, with time, he’s going to progress.”

For the severely disfigured, the goal is to have not just a new face, but a functioning face. A face that allows them to breathe properly, to blink, to smell, to drink from a cup. A face that’s unremarkable. For the faceless the world is an intolerant and hostile place. “We are bringing them to a certain normality so that others can accept them,” said Lantieri.

In some ways, said Pearl, face transplants have become extreme makeover stories. The “big reveal.” “So, rather than this being a story of us having a broader and more expansive notion of the relationship between body and self, it turns into this very conservative, traditional way of thinking, ‘I can’t bear to look at this person. That person is doing me both the favour and the appropriate new thing — getting a new face.’ And I think that’s a shame.”

Face transplants continue to raise troubling ethical questions, about society’s unease with the disfigured and damaged, as well as the meaning of a face, what it means to live with the face of another. But as more face transplants are performed, demand for donor faces will inevitably grow. And more grieving families may agree to give up the faces of their loved ones in the hope that they might “live on” in some metaphysical way.

In the U.S., there have been emotional reunions between the families of donors and recipients — widows seeing their husband in the chin or flushed cheeks of the recipient, touching and stroking him as if they can’t entirely let go of the man whose face it once was.

It is also, according to Lantieri, who has known Borsuk since he was a young fellow in Baltimore, among the best.

An hour before wheeling his patient into the operating room, Borsuk called his French mentor: “He asked if I had any advice to give him,” Lantieri said. “I told him, ‘You’re trained. You know how to do it. You’ve been through it before. Just climb the mountain. I know you can do it.’ And he did an awesome job. It’s perfect. What can I say? I think he had the perfect transplant.”

Today, you can still make out the incision that runs across Desjardins’ face, just beneath his lower eyelids, and down around his neck. His lips are still paralyzed and his face still feels mostly frozen, as if he’s just come from the dentist. He can’t close his mouth, and so he has a surprised look, as if he still can’t quite believe his physical transformation. His gunshot accident had left a wide-open wound in the middle of his face. It’s astonishing he didn’t die. Borsuk said he doesn’t know the circumstances surrounding the accident. “The story wasn’t very clear. He hunts a lot. To this day, I still don’t know, exactly.”

He keeps a picture of Desjardins taken on a cruise ship, before the gunshot blast. He’s tanned and smiling, the ocean behind him. He has bushy eyebrows and salt and pepper hair and ears that stick out slightly.

When he saw his new face for the first time, Desjardins thought he was looking at a picture of another man. “I didn’t think it was mine,” he told me through his wife. His tongue has atrophied. He hasn’t used it properly in seven years, so it’s smaller than yours or mine, because we don’t stop talking. With time, it’s going to regain volume. He’ll be able to swallow again, to speak.

When I first met Borsuk at his clinic, he told me Desjardins had just left and that I almost certainly passed him in the waiting room but didn’t notice anything unusual about the man.

When I finally met Desjardins last week at Maisonneuve-Rosemont, it was picture day. They were preparing him for the “after” photos to be released today. Senior plastic surgery resident Dr. Gabriel Beauchemin carefully trimmed Desjardins’ goatee with an electric shaver. He neatly clipped his mustache with tiny scissors. Desjardins breathed through his mouth. His wife lifted his red and black jersey shirt, and pushed a liquid-filled syringe into the feeding tube in his stomach, then tucked his shirt neatly back in. When Chollet entered the room, he and Desjardins embraced. “Smile,” Chollet said. “Close your mouth,” he said, gently pushing up on Desjardins’ chin.

As he left the examination room, Desjardins walked slowly into the outer waiting room. He turned to look for his wife, who was waiting to take him to the photographer.

People bustled around him. But there were no looks. No stares.

He was just another face in the crowd.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://nationalpost.com/feature/canadas-first-face-transplant