The outbreak is not over, and a new crisis may have begun.

Climate change, human behaviour that changes nature, and "crimes" that destroy biodiversity, such as deforestation, land-use change, intensive agriculture and livestock production, and the growing illegal trade in wildlife, can increase animal-to-human contact and increase the risk of animal-borne diseases spreading from animals to humans.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, 75 per cent of the new infectious diseases that occur in humans every four months come from animals, demonstrating the close relationship between human, animal and environmental health.

The outbreak is not over yet, and the worse is yet to come.

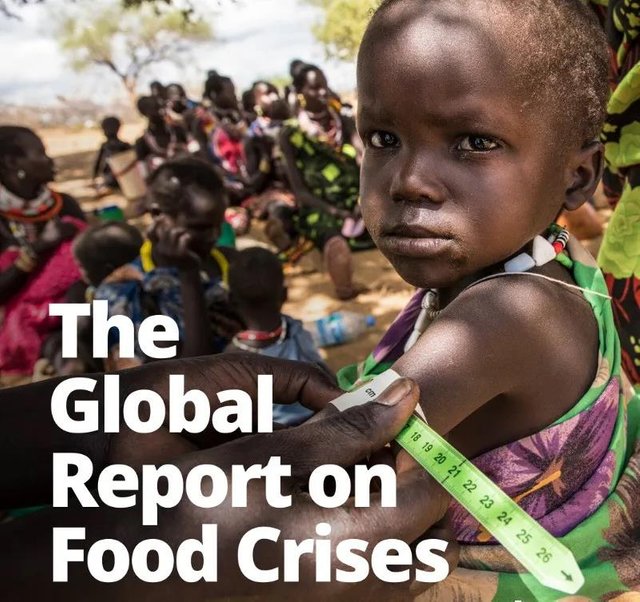

A few days ago, the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) released a 2020 Global Food Crisis Report.

There are several very disturbing numbers in the report:

This year is the worst year for food supplies in more than 60 years because of the new corona outbreak.

Around the world, at least 821 million people sleep hungry at night.

250 million people will suffer from the food crisis, a full 130 million more than last year.

The turning point of the global epidemic has been delayed, and a series of questions about food have followed

Experts believe that the "focus" of global food supply is not on production, but on circulation. In particular, the global food chain is far more fragile than people think, and a series of export restrictions are being imposed, potentially leading to market shortages.

By the end of March, 12 countries around the world had introduced measures to restrict food exports, severely disrupting the entire food supply chain.

So, where is the most food shortage?

The Food and Agriculture Organization says one in five Africans face food shortages.

In Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia, persistent severe drought and years of poor harvests have left 12 million people with food shortages. In December, swarms of locusts attacked their crops again. To add insult to injury, they are now facing a new outbreak of pneumonia.

In addition, the Sahel region of Africa, the Central African Republic, the Congo, South Sudan and so on are also facing the food crisis situation.

French writer Hugo said: Nature is a kind mother, but also a cold butcher.

In the face of the epidemic, panic, fear, we should think about the relationship between man and nature, think about what we should do in the future. Several of the natural life documentaries recommended later have the natural knowledge that everyone in the midst of an outbreak should learn about.

Understanding nature can better create the future of mankind.

The reality is that global demand and consumption of crops are growing rapidly. According to the Global Agricultural Productivity Report 2019, global production needs to grow at an average annual rate of 1.73% by 2050 to provide sustainable food, feed, fiber and animal energy for 10 billion people.

However, the fact that agricultural productivity is struggling to keep up with population growth underscores the importance of technological innovation.

To increase crop yields, scientists at the Institute of Pathogens and Microbiology (PMI) at the University of Northern Arizona are working with researchers at Purdue University to explore bacterial and fungal communities in the soil to see how the microbiome affects crops. They believe that advances in microbial science will eventually help farmers around the world grow more food at a lower cost.

Nicholas Bokulich, an assistant research teacher at PMI, and Greg Caporaso, director of the CENTER for Applied Microbiology at PMI, have been exploring systemic genetics , which studies evolutionary relationships between different plants -- to determine the most appropriate rotation plan.

The team recently published an article in the journal Expedition Atoins on the role of microbiome in agri-food production. This article challenges the traditional rotation view and finds that the effect of rotation on yield may be limited to the seed level, and that factors such as microorganisms may need to be taken into account when designing rotations.

The traditional approach is to rotate distant pro-crops in different years to maximize crop yields.

"There is a hypothesis that plant pathogens are targeted only at a single host, or a very closely related host. So if you grow a crop in an adjacent year that is close to kinship, then the next year the pathogen is likely to be lurking there waiting for their host," Caporaso said, "but this hypothesis has not been directly certified." "

With funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Institute for Food and Agriculture, the team conducted two long-lived experiments. In the first year, Kathryn Ingerslew and Ian Kaplan of Purdue University planted 36 crops and agricultural weeds. These crops include tomatoes, eggplants (the same level as tomatoes, different levels of species), bell peppers (the same level as tomatoes, different levels of the genus), and distant relatives of tomatoes corn, wheat and rye.

The following year, the researchers planted tomatoes in all the test fields. They found that in the fields where tomatoes were grown in the first year, tomato production in the second year was lower than expected, in line with expectations. However, there has been no significant decline in tomato production in any other area.

"The results suggest that while rotation does have an impact on yield, the impact may not exceed species levels," Caporaso said. "

Kaplan, an entomological professor, said: "The results are very surprising because avoiding the rotation of close relatives is a universal rule of thumb, from small-scale gardening to large-scale farming. However, the fact that we have not found any evidence related to crop yields, other than the negative effects of monospecies and monoculture, suggests that other factors need to be taken into account in the design of rotation plans for sustainable agricultural systems. "

Prior to planting the following year, Caporaso and Bokulich used sequencing techniques to explore the composition of bacterial and fungal communities in the soil. They found that annual crops leave traces of the microbiome in the soil, and that plants that are closer to each other are similar to their soil microbiomes.

"We are now able to explore the role of microbes in agricultural systems at unprecedented depth and resolution," Caporaso said. "

In response to the findings, Caporaso asked: "Should we rotate crops with similar soil microbiomes so that beneficial bacteria and fungi already exist in the soil support crops for the next growing season?" "

While the study has not yet found a specific relationship between soil micro-organisms and rotations, another study of the microbiome of the inter-leaf (i.e. the above-ground part of the plant) may have found a causal relationship between microorganisms and plant health.

More and more research proves the importance of plant microbes for the healthy growth of plants. Many microorganisms in the healthy plant microbiome may have specific benefits for plants, such as increased immunity, resistance, or nutrient absorption.

Scientists hope to reconfigure plant microbiomes by means such as manipulating plant genetic systems, so that plants can get more beneficial microbiomes that can improve their own health and yield.

However, the field of plant microbiome is still very young. In microbiome research, we used to focus on human gut flora. But more microbes live on the leaves of our planet's lungs, plants, and if we can better understand how microbes affect the health of crops in natural ecosystems and farmland, we may be able to use them to solve food problems.