The Problem of Creativity and Expertise; A personal exploration . . . with some research

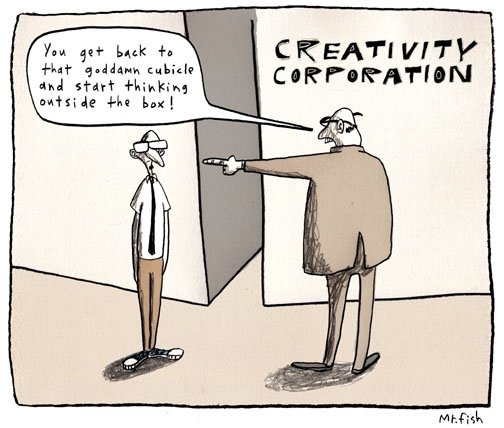

This is a hella a long article, so TL;DR , then read this ):

Because the field of creativity is still relatively new in the scope of other disciplines, researchers are still formulating how to best study, and more importantly, prove creativity. Knowing this, I hope to achieve a deeper understanding of the current research into the field of creativity. Are the current studies using enough of a cross-section of the population? Or, are they utilizing those who, although cost effective for researchers, are actually skewing the results of the research? This post is an introductory and personal exploration of the field, with a closer look at the Consensual Assessment Test (CAT), its brief history, proponents, and alternative hypotheses. Ultimately, I will be considering what constitutes an expert when evaluating a creative artifact (product) for business purposes.

Creativity: A Personal Exploration

Often, when confronted with applying creativity in the domains of business and academia, I feel as if King Lear asking, “Who is it that can tell me who I am” (King Lear 1. 4. 230). Clearly, within business and academia, I feel a lack of confidence and validation from outside sources. As a person who has studied creative acts in the arts (15 years of poetry, play writing, short stories), and worked professionally 20+ years in the creative industry (advertising copy writer, creative director, social media expert), I have more than a vested interest in the field of creativity.

Admittedly, I have often struggled with my confidence within the realms of work and academia, because I felt my style of problem-solving or the end results of my efforts were not appreciated or sometimes considered invalid by management. Although I’ve grown a deeper appreciation of “being” since my youth, I still continue to struggle with confidence and inner-validation of my intuitive problem-solving nature. This, of course, is more felt in business than in academia.

My background includes a varied mix of professional jobs and academic interest. Through the years I have come to many errant conclusions regarding creativity because of building upon other’s myths with my own mythmaking, as well as listening to the perceptions of those who seemed more knowledgeable. Looking back upon my rich and varied life, I see that I have broken many patterns of the myths, such as questioning the sanity of artist, muses, and the like, yet I still allow perceptions of others to influence my intuitive creative nature in business culture, often thinking that as a creative person I must only have value as a poet, playwright, artist, etc, and that creativity in business is of no worth, or at least not recognized.

Renaissance Testing

I consider myself to have a proclivity towards renaissance thinking and learning; connecting an assortment of ideas from varying disciplines of thought that often do not have a direct or obvious connection to the problem, solution, or even domain; accordingly, I have had great success at connecting valuable solutions to problems when allowed. Afterwards, when asked, how I came to the solution, I can only explain that it was a hunch, instinct, or intuition.

Yet, this is very rarely accepted as an answer by those in a business where the quantitative proof is the norm. This has been a great source of frustration and one of the main reasons I decided to attend a master of science in creative studies program, and it was also another reason why I’m so interested in pursuing research that validates the creative person as valid and valuable to organizations.

To me, to be creative is to have the ability to synthesize vast amounts of disconnected information and cull insightful (not original) ideas. I value information from many sources and often read broadly across many domains. Obviously, I would like to compare myself to Leonardo da Vinci, but I do not feel I have mastered all of the fields I enjoy studying. I do like to read and practice many things, but I would not consider myself a master of any. Though, when the ideas synthesize, the resulting solution can be spectacular. What I find most interesting about people such as Leonardo da Vinci, and even Steve Jobs, is they ultimately worked for themselves. I can only conclude that neither of them could take the abuse that domain specific “expert-bosses” would have heaped upon them. And perhaps, at the end of the day, their attitude toward their brand of usefulness was not a consideration of measurement.

As I’ve delved further into research into the validation of renaissance tendencies, and the perception of creative people and creativity in academic research, I was amazed I did not to find more research into attitudes toward creativity. Rather, cognitive research of Person as expert-thinker, or research into the assessment of creative Product rule the day. As I looked more into (what I believe is a lack of research into extrinsic attitude) I found that James Kaufman and John Baer were the majority voice on assessment of creativity —and also champions of using CAT.

Why I suspect a lack of research into perceptions of creativity and the creative person could be summed up by their bold statement:

We agree with Carson (2006) that the CAT is the “Gold Standard” in creativity research, but researchers using the CAT need to > justify the judges they use. If the judges are experts in a domain, that is enough justification [emphasis added]. To the extent > that judges are either novices or quasi-experts, researchers must make a case for why the judges they have chosen are > appropriate (Kaufman, 2009, p. 231).

The Consensual Assessment Technique (CAT), which was developed by Teresa Amabile in 1982, rests on testing the creative value of a product by experts within a given domain. Although Amabile points out the CAT may not be appropriate to all domains, especially esoteric ones (Amabile 1983), and others in creativity assessment research concur with Kaufman et al, (2012), that the CAT is not the go-to assessment for evaluating the creativity of a product. Thus, with such consensual agreement, it would only make sense to make bold statements regarding the value of such assessments.

Creativity assessment is a tricky business, as pointed out by almost everyone in the field; and like most academics, there is a want of hard proof of any hypothesis. Although I believe creativity can be measured, I have a problem with how test are constructed for and by experts in any give domain, often to the exclusion of those who could add creative value to domains outside of their expertise.

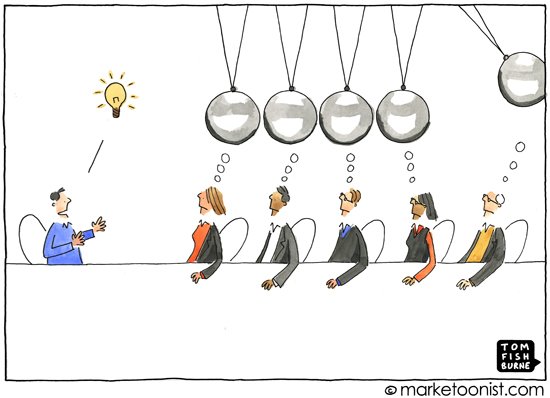

via Marketoonist

The CAT

Mostly, with assessment techniques of creativity, I found studies of CAT within academic domains interesting, and problematic at the same time. For example, much of the research points to applying the CAT to the domain of literature, and in particular to poetry for two reasons. First, this domain was chosen because it is considered a highly creative sub-domain, and rightly so, and second, the researchers have access to the research subjects, namely college students and professors of literature.

The ultimate goal of CAT was to prove the hypothesis that experts in a particular domain are the best judges of creative artifacts within that domain. After several research studies conducted, many conclusion have been drawn from the data by those in the field, which is problematic to me. Again, I point out I am new to creative research and that my initial research into the subject matter is novice at best, but the point of my argument is that people outside the domain, or people with very little relevant experience can still be valuable judges of all sorts of criteria, including creativity. The academic experts might have a higher knowledge base than the general public, a definite disparity itself, but I argue that knowledge is a very much different realm from creativity. Although helpful, still different.

Kaufman et al, point to results showing there were distinct disparities between experts’ and non-experts’ opinions when evaluating creative artifacts (poetry), and incidentally, that inter- rater reliability was a positive indication of support of the hypothesis that experts in a given domain are needed to assess the creative value of an artifact.

However, I must disagree with their argument on the grounds that they went against Amabile’s suggestion that experts might not have more validation within esoteric domains. For instance, I argue that poetry, by todays reading standards, can be viewed as an esoteric domain. I spent an enormous amount of time studying the theory and techniques of poetry and have found that the art of poetry is indeed as esoteric to the general population, as say discreet mathematics.

In addition, the literature experts in this study could very well judge a product uncreative due to filters they have in place from years of deep study of poetics. And more importantly, the students (the novices in the research study) are at more of a disadvantage because of the lack of poetics in secondary education. Of course, unless one considers the cursory two weeks of Shakespeare in a high school English class to be sufficient to lend even a basic relevant fluency in poetry, then I would argue that the CAT study would have been better augmented by a study participants in the median age of fifty or sixty years of age, across varying levels of educations, and across different economic systems. Perhaps, those diverse populations would bring a different kind of expertise through life experience, and I suspect a better classical liberal education if they at least made it through high school. I suggest these would be better novice test subjects than would current college students.

Alternatives to CAT

Craig Gruber argues for a philosophical pragmatism approach when assessing creativity, saying that judgement is true if it reveals and explains our experiences, and continues to be so until proven otherwise (2012). Gruber’s assertion that a pragmatic view of assessing creativity is interesting because it points to what J. M. Fox has said about creativity in lectures, specifically, “each individual is the locus of creativity” (personal communication, June 12, 2012). I think this is crucial when designing research around assessment of creativity in general, and the value of a creative product particularly. Similarly, other creativity researchers are looking into social and cultural indicators regarding the judgment of creative artifacts (Glăveanu 2011). I’m in agreement with this approach to studying and researching creativity, especially socio-economic aspects. As an example, I believe that recognizing the interconnectedness of all domains through the lens of creativity would lend itself to more data, although more likely it would be qualitative, and therefore not as appreciated in the current reductionist view of knowledge that one finds in academia.

Renaissance tendencies tend to be ignored in most domains, so academia should not be any different. Until as little as 20 years ago, academic departments rarely worked on projects with those outside of their discipline. I have witnessed this as recently as several years ago. Many times, I felt isolated within my department. For instance, while studying literature, I sometimes wanted to synthesize information from astronomy, computer programming, or biology, yet I was never allowed to do so. As a rule, academics in literature tends to take a reductionist view of poetry, and as such, dissect poetics apart according to current trends in poetic theory. However, poetry, according to poets, is a sort of controlled paradoxical chaos —a craft that may have rules for style, but otherwise attempts to thwart collective human experience and cognitive metaphors in the effort to show a different facet of the human experience.

Poetry by it’s very nature is what I would call the wild west of literature, and the human expression of universal things in exact and minute experiences. The serious poet is an active agent in creativity, and tends to be the driving force of change toward a true creative product, constantly shifting the landscape away from theory, and moving ever closer to a nirvana of new language and new experience.

Poetry, therefore, is the furthest artifact I would use when designing a test for expert and non-expert evaluation of creative product. I would instead use an instrument that people are generally comfortable with, such as common and frequent language devices, which can be manipulated for creative impact. For instance, I would use a structurally familiar artifact, which uses creative constructs of language, such as short stories.

Kaufman et al, do resistantly agree. They found that novices, quasi-experts, and experts were closer in test numbers when tested against short stories (Kaufman 2008). And again, when the study was run again at a later date using different short stories, and different study participants, “the results were better for short story ratings (Kaufman 2009), than were with poetry.

This might support my arguments that poetry, even for educated college students, is still too esoteric for assessing creativity. For instance, when the same test were ran against short stories, the inter-rater reliability between novices were within acceptable ranges of the experts, and that quasi-experts were near identical to experts when rating criteria of the over-all result of creative artifacts. This supports my argument that academic experts who study poetry theoretically are quite different from poets who seriously study poetry, and by proxy intrinsically understand both the theory and the act of creativity. For instance, would the same academic experts (Phd’s in literature) see spoken word poetry, or other less “refined” poetry as uncreative artifacts? I’m typically suspicious of academic experts who make judgements about domains without some sort of deferment to artist’s culture or “working man,” in essence, the very people who do it, oppose to study the being of it.

And apparently, until recently, most academics viewed spoken word with humor, if not disdain. Fortunately, there has become more acceptance with the height of post-modern theory in literature, which advocates for the voices of the disenfranchised and minority groups, basically those who supplant studied art or rather the accepted conventions in the arts. Likewise, Charlan Nemeth makes a valid point regarding expertise. She states that novices only need to bring a basic knowledge set to the domain in order to promote creativity (Nemeth 1974). Additionally, I hypothesize that by adding novices to the judgement of creative product, it allows the experts to think differently and discover novel and useful artifacts. Of course, other researchers note, “What might seem very original to someone outside a domain might seem totally pedestrian to someone with expertise in that area” (Kaufman 2012). I do see Kaufman’s point; however, is this a problem of a novice recognizing creative value in product, or is this a problem with expert not seeing the creative potential? Again, I point back to Amabile who states that some products may be so original that domain experts fail to appreciate its worth (Amabile 1983).

Conclusions

I understand the importance of valid and provable research in the field of creativity. I agree that there must be further assessments and studies done in order to give the field further foundation within those domains that require quantitative proof —namely business. However, it is important that we honor the creative personality of all people, and not allow it to exclude the diversity of those within certain socioeconomic and class based systems; ones who cannot afford formal education, but have renaissance tendencies all the same.

I understand the need to control research cost in academia, but I also understand the ease with which finding study participants within academia, thus making it appealing. But using professors as the experts and colleges students for novices when both are typically highly educated when compared to vast majority of population just seems myopic. Consequently, by running these studies to prove their hypotheses, and thus attempting to gain respectability in the field of creativity, those in the field must take it to the next step and run cross-sectional studies of general populations. Obviously, the current studies are not true cross-section studies, thus neither giving true representation of creative judgement, nor representation of the diverse creative potential of a larger population. We must open our studies to those outside of academia’s walls before we cause more harm to the creative field, adding to the ivory-tower syndrome of theory upon theory, until it’s barely practical anymore.

After all, the custodian, the secretary, or construction worker could all give valuable solutions to their employers.

As the creativity field continues to blossom, I hope to be on the forefront of research, and build my own comprehensive theory on the shoulders of the giants in the fields. Yet, I want to ensure that this fields stays as far away from building a wall, and thus becoming a field so esoteric in itself that it keeps those who could benefit away from the fruits of the research. After all, the custodian, the secretary, or construction worker could all give valuable solutions to their employers. But, if we “expertise” creativity too much, then these people will not have a voice or find validation of their innate and learned creativity. After all, many innovative and inventive people never even finished high school, and some not even formal school of any sort. Would they still have done so if academia tested their ideas first?

I love creativity and how it applies to business. I have forthcoming book on creativity and entrepreneurship.

References

Amabile, T. (1983). The social psychology of creativity (illustrated ed.) New York: Springer- Verlag.

Glăveanu, V. P. (2011). Creating creativity: Reflections from fieldwork. Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science, 45(1), 100-15. doi:10.1007/s12124-010-9147-2 Kaufman, J. C., & Baer, J. (2012). Beyond new and appropriate: Who decides what is creative?

Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 83–91. doi:10.1080/10400419.2012.649237 Kaufman, J. C., Baer, J., & Cole, J. C. (2009). Expertise, domains, and the consensual assessment technique. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 43(4), 223-233. doi:10.1002/j. 2162-6057.2009.tb01316.x

Kaufman, J. C., Baer, J., Cole, J. C., & Sexton, J. D. (2008). A comparison of expert and nonexpert raters using the consensual assessment technique. Creativity Research Journal, 20(2), 171–178. doi:10.1080/10400410802059929

Nemeth, C. (1974). Social psychology : Classic and contemporary integrations. Chicago: Rand McNally College.

Great. Thanks for sharing. I'm starting to follow you.