Cryptocurrencies as a Free Market

Note: this is a copy of my article on Medium.

Cryptocurrencies are here to stay. Yet they’re not problem-free. I’ll look at how cryptocurrencies are vulnerable to the weaknesses of free markets.

Future of cryptocurrencies: the optimistic view

In a simplified economic theory, the free market is an optimization mechanism that, given enough time, eventually arrives at a competitive equilibrium. The equilibrium is Pareto-optimal in a sense that once it’s reached, no one can improve the outcome for one of the participants without making the overall situation significantly worse. That is, whatever correction is applied, it always cumulatively hurts some participants more than it cumulatively benefits the others.

When this idea is applied to the future of cryptocurrencies, the envisioned outcome is that:

- a few cryptocurrencies eventually win, and establish themselves as global reserve currencies;

- hundreds-to-millions of them find their applications in specific evolutionary niches;

- the rest simply die out. This includes the fraudulent and shady ones. It also includes cryptocurrencies that honestly attempt to deliver value, but fail at that — for example, because they have insufficiently solid engineering; or because they do not solve any real problems; or because there are better currencies solving the same problems; or because they’re against the spirit of whatever a good cryptocurrency should be, politically.

This is the “optimistic view”. It also presumes that the cryptocurrency market is democratic, in the sense that everyone can join this market; that everyone’s amount of control over the market is proportional to their merit; and that participants of the market have their best long-term interests at heart.

20/ Blockchains are a new invention that allows meritorious participants in an open network to govern without a ruler and without money.— Naval (@naval) June 21, 2017

Before talking about the problems, I want to stress that this democratic freedom to influence the future landscape of cryptocurrencies clearly exists — to some extent — and is a really good thing. The possibilities are best expressed by Andreas Antonopoulos:

In the new network centric world, currencies occupy evolutionary niches. They evolve, like species, based on the stimulus they have from their environment. Bitcoin is a dynamic system with software developers that can change it. The question is, which direction will bitcoin evolve?

— Andreas Antonopoulos, The Internet of Money

The evolution and design space of cryptocurrencies

Let’s take a step back and look at how cryptocurrencies evolve. In this process, there are three main groups of actors. The first group is the developers of the cryptocurrency: people who are in the control of the source code, and come up with new ideas to implement. The second group is the infrastructure providers, such as the miners in the bitcoin ecosystem or the operators of full nodes in the IOTA ecosystem. They are responsible for running the network on which the cryptocurrency operates, and may chose to accept or reject the updates proposed by developers. Finally, a currency also needs adopters: people using or holding that currency. The adopters, in some sense, “approve” or “reject” the changes by investing or divesting into the currency. As a result, the adopters are among the groups that determine which design choices gain more traction.

In a technical system, some of its design choices are technically determined: one of the options leads to a system that is clearly better. Unfortunately, this rarely happens in practice. Many of the choices are necessarily political. How to recognize the effects of such a political choice? One evidence for that is a corresponding split in the cryptocurrency design space. It might be something obvious, such as the fork between Bitcoin Core and Bitcoin Cash. As another example, consider the question “How much privacy is sufficient and desirable?”. Bitcoin and most other coins do not give any privacy guarantees to their users; they’re pseudonymous at best. On the other hand, fully anonymous cryptocurrencies are technically possible. Monero and some other “privacy coins” have gained significant market share. Here, Bitcoin and Monero are examples of two different answers to the privacy question.

The basic proposal here is that cryptocurrency adopters are going to “vote with their money” and in this way direct the evolution and politics of cryptocurrencies. Once again, this view is masterfully articulated by Andreas:

In the choices we make with these currencies, we are also choosing to align ourselves with a community. [..] When I choose to adopt bitcoin, I am a believer in a monetary policy of 21 million total coins as a stable source of value. If I choose to adopt Freicoin, I am a believer in inflationary-basis, demurrage coin that has a negative interest rate, that enforces consumption and discourages hoarding. [..] You want inflation? Use an inflationary currency. You’re a goldbug? Use a deflationary currency. You want a currency that creates a guaranteed minimum income for the poor? Use a currency that expresses these politics. You want a currency that puts aside tokens for carbon sequestration? Use a currency that expresses your green politics.

— Andreas Antonopoulos, The Internet of Money

The problem

A decision can be beneficial just for some of the decision-makers. A decision can also be beneficial for all of the decision-makers, but not for the wider society. Finally, a decision can be beneficial for all or most of society in the short term, but not in the long term.

The crucial question here is about the free market: is it capable of ensuring that the best long-term-universally-beneficial decisions win?

I think that with regard to cryptocurrencies, as they exist at the moment, the answer is “no”. Cryptocurrencies are highly vulnerable to market failures.

In the long term, these failures may lead to a number of bad outcomes: from some investors losing their money, to cryptocurrencies remaining a marginalized, possibly illegal field that fails to deliver much of a real value.

Eliezer Yudkowsky analyzes market failures in his book Inadequate Equilibria. He comes up with three ways how free markets lead to suboptimal results (using his terms, market equilibria that are not “adequate”):

- Cases where the decision lies in the hands of people who would gain little personally, or lose out personally, if they did what was necessary to help someone else;

- Cases where decision-makers can’t reliably learn the information they need to make decisions, even though someone else has that information; and

- Systems that are broken in multiple places so that no one actor can make them better, even though, in principle, some magically coordinated action could move to a new stable state. (Suboptimal equilibria)

The next three sections will go into detail about how these problems apply to cryptos.

Decision-makers that benefit from suboptimal decisions

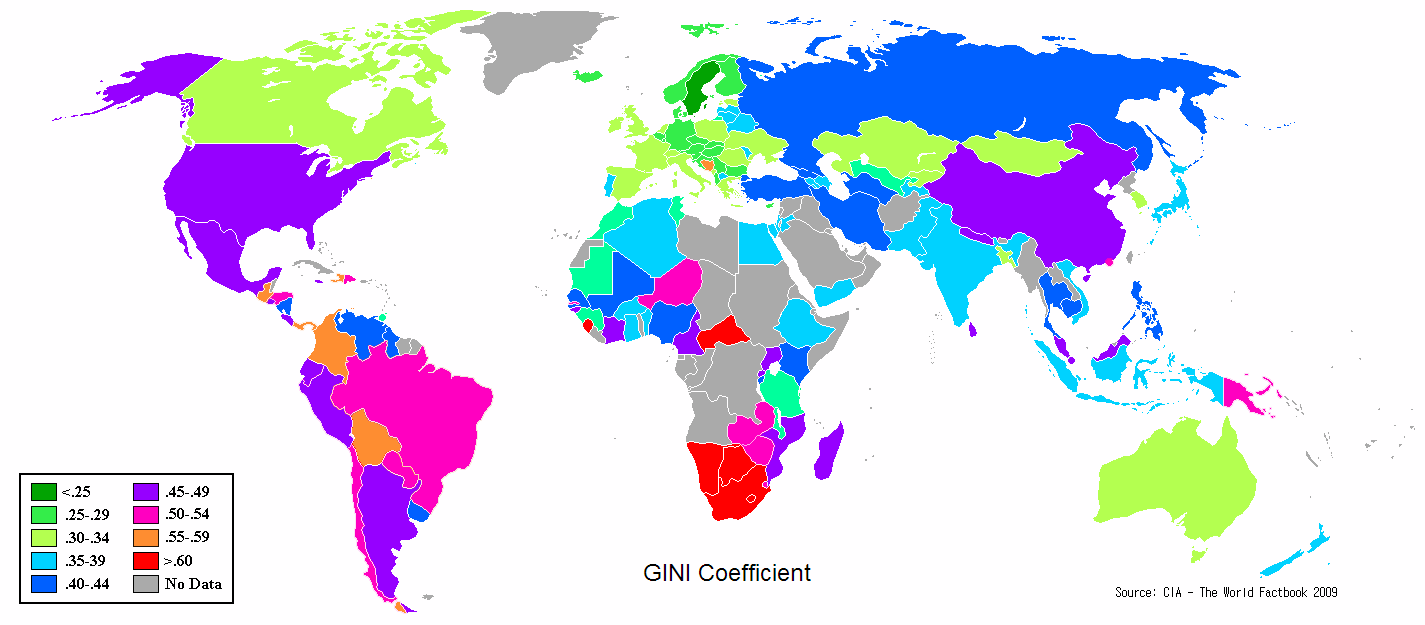

The early adopters of bitcoin receive far higher rewards than the late ones. Many altcoins are even worse, due to a large amount of pre-mined coins owned by the developers or ICO investors. This may sound fine — if you’re not concerned with financial inequality. However, in the crypto world, you should be. The Gini coefficient of bitcoin is estimated to be from 0.65 (https://taylorpearson.me/crypto2017/) to 0.88 (http://www.businessinsider.com/bitcoin-inequality-2014-1). For comparison, it’s estimated to be 0.41 for the USA in general and 0.51 for Brazil, which is on the high side.

Unlike inflationary fiat currencies, bitcoin does not incentivize investing. Rather, due to the deflationary nature of bitcoin, hoarding your wealth in coins is an objectively better decision than putting it back “in the economy”. This is by design. The bitcoin wiki covers why the resulting “deflationary spiral” would not endanger bitcoin as a means of exchange; however, the wiki article fails to respond to the concerns of inequality. At the moment, very few cryptocurrency enthusiasts are seriously concerned about the runaway deflation. Clearly, it sounds like a good thing for the early investors (and for those that believe in the Austrian economics) — but in a more traditional interpretation, in case a deflationary cryptocurrency is universally adopted, it will cause a huge slow-down of economics.

Finally, everyone knows cryptocurrencies are too volatile to be attractive for everyday use. “But that’s only for now, only while they’re small?” Doubtfully. This inconvenience is not something that will disappear on its own. To understand why, look at how fiat currencies are kept stable by the central banks. The banks achieve this by issuing extra money “out of thin air” and by removing money from the market. These two mechanisms are seen as controversial by bitcoin enthusiasts; non-regulated, fixed-amount cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin are impossible to control in this way, by design. However, empirical data clearly show that even small fiat currencies are on the average much less volatile than bitcoin. Same goes for gold; one can argue that it’s because gold has a universally accepted intrinsic value, unlike bitcoin. (To be clear, bitcoin also has such a value in my opinion; it can never drop to zero; the issue is that its not likely to become a universally accepted opinion anytime soon.) Perhaps currencies with more obvious intrinsic value are preferable, as they should reduce the volatility of price. The candidates include both platform and utility currencies (think of Ethereum and FileCoin, respectively). Lastly, large centrally-controlled “reserve” pool of coins is another option, as demonstrated in practice by Ripple — although this comes with its own obvious problems due to centralization.

Properly implemented, democratic governance could reduce the downsides of current cryptocurrencies without giving excessive control back to undemocratic central entities. Consider the example of net neutrality. The Internet can only be truly neutral if there’s a legislation for that, and a government ready to protect this legislation.

Decision-makers who fail to gather information necessary for good decisions

Cryptocurrencies are becoming more global and more mainstream, but the vast majority or cryptocurrency enthusiasts are still young males. Perhaps more to the point, they are also far more likely to be libertarian (37% according to this infographic, data from 2013–2015) than the general population. A priori, letting a field to be controlled by such a narrow subgroup is not a good recipe for anything. There is a high risk that some crucial pieces of information — for example, some valid points from the public opinion —will fail to reach the decision-makers.

Then there’s the speculative nature of many investments. I’m sure that everyone following cryptocurrencies can come up with their own examples of investor irrationality, often in the form of *“coin X shouldn’t be anywhere near that valuable.” I won’t spend much time on this, just point out a single exampl e that Dogecoin is nice — as far as meme coins go — but in a more conservative market it would hardly have a market cap north of 1 billion dollars! This exuberant optimism seems at least partially unsubstantiated. It shows a failure to invest wisely; therefore it’s difficult to claim that the cryptocurrency evolution is directed by the inventors in the “best possible” directions.

e that Dogecoin is nice — as far as meme coins go — but in a more conservative market it would hardly have a market cap north of 1 billion dollars! This exuberant optimism seems at least partially unsubstantiated. It shows a failure to invest wisely; therefore it’s difficult to claim that the cryptocurrency evolution is directed by the inventors in the “best possible” directions.

Meanwhile, cryptocurrency developers have irrationalities of their own. It seems they often get carried away by the features and functionality of their products, at the expense of caring about robustness, thoroughness, and the user experience. One of the most notorious examples of this problem is the failure of the Ethereum’s DAO in 2016. It was caused by a known bug in the Solidity language; due to an incredible optimism the developers of the DAO’s smart contract, they thought that this bug does not apply to their case. For another controversial example, consider the vulnerability in IOTA’s custom hash function. It’s hard to see how the plan to use custom, relatively less-tested cryptographic functions is anything else than an example of unsubstantiated optimism. It seems that the developers in such cases are not so much missing any specific pieces of information, but rather fail to “get into” the appropriate mode of thinking.

The final example in this section is that of “utility coins”: coins associated with selling storage space, DNS names, distributed computing power and so on. Almost none of these coins provide any real-world utility at the moment, and few of them have realistic plans to deliver that in the short-term future. Hopefully, increased regulation of initial coin offerings will improve the situation in 2018. The issue is not only to weed out clear scams, but also to create more incentives for the overwhelming majority of honest developers to be better at doing market research before doing the ICO. The goal for the developers should be to find out what would really deliver the highest potential value to the prospective users of these utilities, rather than go for whatever generates the most of excitement and looks the best on the paper.

Suboptimal equilibria

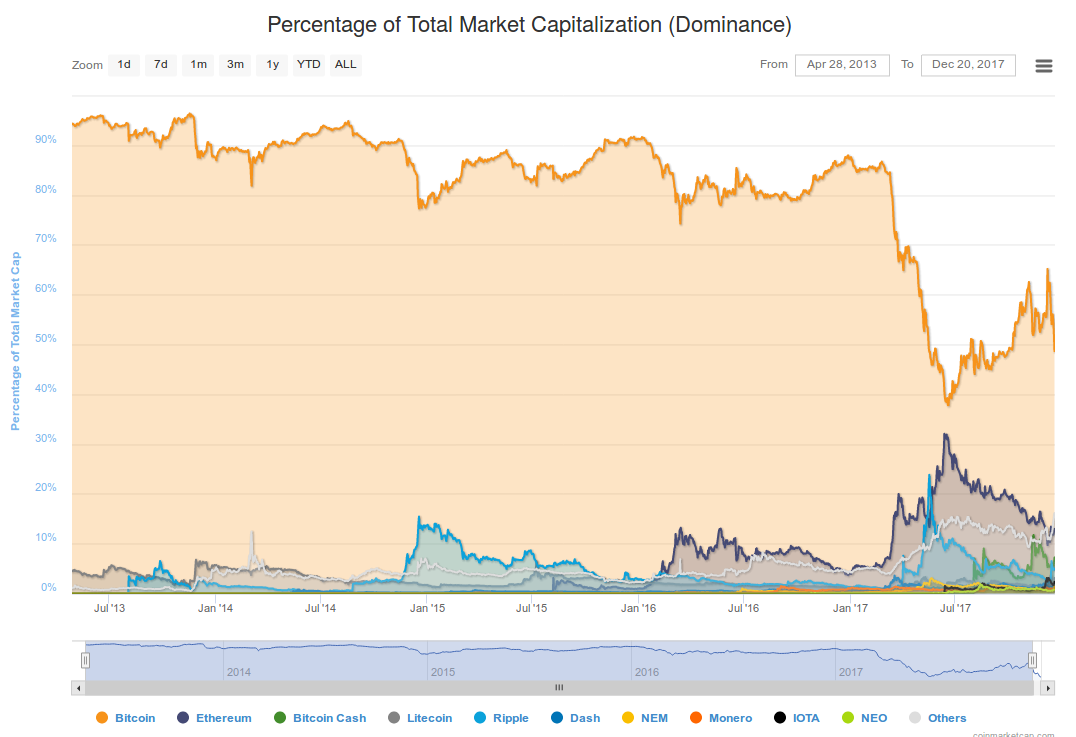

In the late 2017 Bitcoin was by far the most popular cryptocurrency, having around 40–50% market share. (It’s down to 38% at the moment, but it’s highly likely that it will bounce back.) Bitcoin had the first mover advantage; it successfully used this advantage. The network effect has been working on the behalf of bitcoin since 2009.

However, at the moment bitcoin is also one of the least practical cryptocurrencies, at least for everyday use. The median transaction fee peaked to more than 30$ and remains above 10$. These numbers suddenly make Western Union fees attractive. There are 135563 unconfirmed transactions on the blockchain (on January 2, 2018). These scalability problems are caused by bitcoin’s impractically small block sizes. One of the reasons why block sizes are kept so small is to ensure that bitcoin mining remains decentralized. However, this goal has not been reached; in contrast, the top three most powerful bitcoin mining pools now control more than half of the network’s hashrate. Finally, the proof-of-work mechanism used in bitcoin mining is so wasteful that it famously consumes more energy than 150 of world’s countries.

Practically any mid-ranked cryptocurrency improves upon bitcoin in some aspects. However, these mid-ranked currencies do not have the bitcoin’s critical mass. Only truly game-changing improvements such as the addition of smart contracts almost makes other currencies competitive. Here the problem is that even if all the players in the market see currency X as better than bitcoin, they know that, as self-interested rational actors, they should adopt currency X instead of bitcoin only if they’re sufficiently certain that the other players will make the same move in soon-enough future. (And that they will not, for example, pick currency Y instead). Reaching such a level of certainty is very difficult in a truly decentralized system, so we’re likely to be stuck with this suboptimal situation for a while. Or, if bitcoin does get either replaced or significantly improved, with other similar suboptimal equilibra in the future.

There are plenty of other examples for this kind of failure. For example, everyone trades on centralized exchanges despite the obvious drawbacks (such as high risks of hacking or fraud) because that’s where everyone else trades. We can only hope that tech developments will create sufficient pressure for everyone to migrate to better solutions in the future; for example, to decentralized exchanges.

A counterexample

When writing this article, I come to realize that there already is a currency that withstands most of these criticisms! It is Cardano (ADA).

- The team includes cryptocurrency veterans, and has “done its homework” by surveying the state and the problems with previous generation cryptocurrencies.

- The people in its engineering team (https://iohk.io/team/#cardano) have academic backgrounds; presumably, they are well aware of the state-of-the-art techniques in computer science and software engineering — as is confirmed by the subsequent points.

- The development is relatively slow, but thorough, following a detailed roadmap.

- The Cardano team plans to use a functional, Haskell-like language for its smart contracts. Such a language is presumably much better amenable to formal analysis that the existing smart contract languages.

- The team uses formal methods, and has already produced a peer-reviewed formal correctness proof of Cardano’s proof-of-stake mechanism.

- The Cardano team is ready to work with regulators, going in the direction suggested in the previous section: it aims to “balance the needs of users with those of regulators” in order to achieve “greater financial inclusion”.

The main drawbacks of Cardano in my opinion are:

- The relatively slow development means that most of its envisioned technology does not exist at the moment. There can be no guarantees that it will be implemented as planned and on time. Software projects fail — a lot.

- Even assuming the technology is successfully implemented and on time, faster-moving currencies such as Ethereum might effectively lock-in the market before Cardano is ready.

- Formal correctness proof of a specification does not mean that the implementation is bug-free.

How did we get here and what’s next

As a technology, blockchain is one of the most important recent inventions in computer science. Cryptocurrencies are the first applications of blockchain, and they have world-changing potential.

The problem is that most people do not realize this yet; in the current public consciousness, they’re seen as speculative investment assets at best. I have gone through this path myself: from dismissing them as irrelevant in 2011, to investing a little in 2013, to excitement in 2017.

This is not surprising: cryptocurrencies are technically complex and feel politically alien. At the same time, the ideas behind cryptocurrencies are inherently democratic. I’m optimistic that more people will get involved into cryptocurrencies in the future, and that they will make the market more rational and democratic at the same time. We, as technologists, should help them by creating easier-to-use tools and ecosystems. We also should help by educating the people so they better appreciate the “big picture” view of cryptocurrencies and make better-informed decisions.