Why Can't Science Explain Consciousness? | Live Science

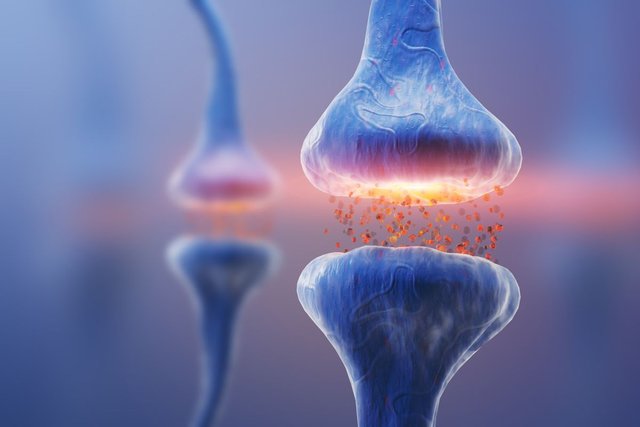

Explaining how something as complex as consciousness can emerge from a grey, jelly-like lump of tissue in the head is arguably the greatest scientific challenge of our time. The brain is an extraordinarily complex organ, consisting of almost 100 billion cells — known as neurons — each connected to 10,000 others, yielding some 10 trillion nerve connections.

We have made a great deal of progress in understanding brain activity, and how it contributes to human behavior. But what no one has so far managed to explain is how all of this results in feelings, emotions and experiences. How does the passing around of electrical and chemical signals between neurons result in a feeling of pain or an experience of red?

There is growing suspicion that conventional scientific methods will never be able to answer these questions. Luckily, there is an alternative approach that may ultimately be able to crack the mystery.

For much of the 20th century, there was a great taboo against querying the mysterious inner world of consciousness — it was not taken to be a fitting topic for "serious science." Things have changed a lot, and there is now broad agreement that the problem of consciousness is a serious scientific issue. But many consciousness researchers underestimate the depth of the challenge, believing that we just need to continue examining the physical structures of the brain to work out how they produce consciousness.

The problem of consciousness, however, is radically unlike any other scientific problem. One reason is that consciousness is unobservable. You can't look inside someone's head and see their feelings and experiences. If we were just going off what we can observe from a third-person perspective, we would have no grounds for postulating consciousness at all.

Of course, scientists are used to dealing with unobservables. Electrons, for example, are too small to be seen. But scientists postulate unobservable entities in order to explain what we observe, such as lightning or vapor trails in cloud chambers. But in the unique case of consciousness, the thing to be explained cannot be observed. We know that consciousness exists not through experiments but through our immediate awareness of our feelings and experiences.

So how can science ever explain it? When we are dealing with the data of observation, we can do experiments to test whether what we observe matches what the theory predicts. But when we are dealing with the unobservable data of consciousness, this methodology breaks down. The best scientists are able to do is to correlate unobservable experiences with observable processes, by scanning people's brains and relying on their reports regarding their private conscious experiences.

By this method, we can establish, for example, that the invisible feeling of hunger is correlated with visible activity in the brain's hypothalamus. But the accumulation of such correlations does not amount to a theory of consciousness. What we ultimately want is to explain why conscious experiences are correlated with brain activity. Why is it that such activity in the hypothalamus comes along with a feeling of hunger?

In fact, we should not be surprised that our standard scientific method struggles to deal with consciousness. As I explore in my new book, Galileo's Error: Foundations for a New Science of Consciousness, modern science was explicitly designed to exclude consciousness.

Before the "father of modern science" Galileo Galilei, scientists believed that the physical world was filled with qualities, such as colors and smells. But Galileo wanted a purely quantitative science of the physical world, and he therefore proposed that these qualities were not really in the physical world but in consciousness, which he stipulated was outside of the domain of science.

This worldview forms the backdrop of science to this day. And so long as we work within it, the best we can do is to establish correlations between the quantitative brain processes we can see and the qualitative experiences that we can't, with no way of explaining why they go together.

Shared On DLIKE

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2019-11-science-consciousness.html