Ending the Mexican-American War on Drugs

What if there was no more drug-related violence? No more gang wars over clientele or territory? No more useless murders, destruction of land, property, illegal immigration, prostitution, or distribution of illegal goods? Is there a feasible answer to solving this problem of drug wars and their lack of success on ending drug trafficking and violence? Could ending the prohibition on drugs put an end to the drug wars and violence by eliminating their black market? The war on drugs is failing. By ending this war, drug-related violence would stop.

According to the Council on Foreign Relations’ Foreign Affairs, The majority of illicit drugs consumed in the United States come through or from Mexico, and virtually all the revenue of Mexican drug-trafficking organizations comes from sales in the United States. This includes cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines, and cannabis (Stewart 2012). This is a business, a big business. Not to mention the U.S. and Mexican government’s efforts to control and deter this activity from happening.

Both the United States and Mexico spend millions of dollars each year on border control, drug searches, drug arrests, drug-related violence, and more only to have the problems reoccur month after month. More than a thousand people die each month due to drug-dealing violence in Mexico alone, and in some parts of the country, even police forces find themselves outgunned by drug traffickers. These crimes, on going for decades, have affected the lives, liberty, economies, and policies of millions of people in both countries. How has this war affected so many people, and can a peace be found?

Many agree that illicit drugs and controlled substances are better off that way (Stossel 2012). After all, many of these controlled substances are very hazardous to one’s health, habit-forming, and would potentially cause great problems if freely sold and distributed in the community. As convincing as these points may be, the problems with controlling and prohibition of substances are often overlooked. Within the drug trade there is on-going violence, death of innocents, financial corruption, and corruption with authorities, incarceration rates, and financial costs to society that could potentially be stopped with the lifting of prohibition in both countries. Examining these problems in both cultures, I hope to illustrate the disheartening waste and moral costs in the name of morality.

In addition to these, I would like to illustrate the disasters of the wars within the drug market, as well as the wars against the drug market. Both of these are useless and cost lives and millions of dollars. Finally, I would like to examine answer the question: “Could ending the prohibition on drugs in the U.S. and Mexico put an end to the drug wars and violence by eliminating their black market?” as the Mexican drug war has been going on for decades.

By consulting both American and Mexican government statistics, news reports, peer-reviewed articles, I hope to establish grounds that demonstrate the war with the black market to perpetuate itself, and the war outside the black market that seeks to stop it are both tragic and useless, and that ending prohibition in one or both countries would be greatly beneficial to the peoples of both.

In the spring and summer of 1973, the United States House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate heard months of testimony on Richard Nixon’s Reorganization Plan Number 2, which proposed the creation of a single federal agency to consolidate and coordinate the government’s drug control activities (DEA 2011). The Drug Enforcement Administration was created by President Richard Nixon through an Executive Order in July 1973 in order to establish a single unified command to combat "an all-out global war on the drug menace." At its outset, the DEA had 1,470 Special Agents and a budget of $75 million (DEA 2011).

Today, the DEA has nearly 5,000 Special Agents and a budget of $2 billion (DEA 2011). The DEA’s mission is to enforce controlled substance laws and regulations of the United States or any other competent jurisdiction, those organizations and principal members of organizations, involved in the growing, manufacture, or distribution of controlled substances appearing in or destined for illicit traffic in the United States; and to recommend and support non-enforcement programs aimed at reducing the availability of illicit controlled substances on the domestic and international markets. In other words, the DEA strives to blockade and eliminate illicit substances or the product and distribution in order to shut down the drug market. The United States government has put pressure on Mexico due to drug trafficking and has therefore has influenced Mexican domestic and foreign politics, arguably to the benefit of the U.S. as it was thought that drugs and illicit substances had little damage done to Mexican society. This movement proved to be efficient during the 1970s by Operation Condor, implemented by the Nixon administration in 1969 (Chabat 2002). An obvious flaw in this movement is that it does not eliminate the demand for illicit substances and products.

Since the demand for illicit substances still exists, the market of illicit substances still exists and therefore provides an opportunity for high-profit business. Jorge Chabat discusses the affect that illegal drugs and drug trafficking have on Mexico in his article “Mexico’s War on Drugs: No Margin for Maneuver”. He states that Mexico is a natural supplier to the biggest illegal drug market in the world, the United States (Chabat 2002). This black market of potential high-profit is where drug cartels come in.

A drug cartel is an organized crime group mainly dedicated to the production, trafficking, and distribution of drugs. Drug cartels often are also involved in illegal possession and distribution of firearms and other weapons to protect and perpetuate their markets. Cartels are often involved with extortion, money laundering, and violence with innocent people as well as people within cartel organizations who may be a threat or hindrance to their market. Since the market base of cartels is illegal, the operations of production, trafficking and distribution are done underground or illegally. This drives crime in terms of corruption, violence towards fellow cartel members, and underground operations of importing and exporting via smuggling.

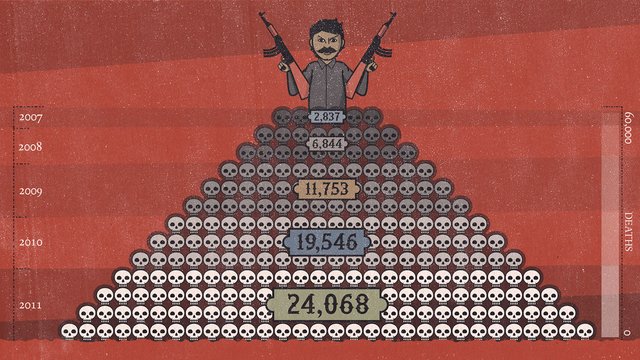

Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman is the leader of the Sinaloa Cartel. This northwestern cartel has operated by smuggling cocaine in baggage on commercial flights, transporting larger amounts on small private aircrafts, and eventually exported multiple tons of cocaine on the cartel’s own 747s, sometimes transporting up to thirteen tons of cocaine (Keefe 2012). “They used container ships and fishing vessels and speed boats and submarines, crude semi-submersibles at first, then fully submersible subs, conceived by engineers and constructed under the canopy of the Amazon, then floated downriver in pieces and assembled at the coastline. These vessels can cost more than a million dollars, but to the smugglers, they are effectively disposable. In the event of an interception by the Coast Guard, someone onboard pulls a lever that floods the interior so that the evidence sinks; only the crew is left bobbing in the water, waiting to be picked up by the authorities.” (Keefe 2012). Engineering and shipping operations such as this put a dent in the sound economy by pulling hundreds to thousands of workers from what would be conventional labor to illegal and un-taxed business. Not only do these operations pull from the economic work force, but they artificially create importing and exporting routes as well as distribution hubs both at large and on street levels. Cartels then face navigating and battling law enforcement as well as other cartels for various turfs. Since 2006, intelligence accounted 50,000 deaths of both civilians and cartel members in Mexico alone, thought to be attributed largely to turf wars (Keefe 2012).

Mexican drug cartel turf wars are even fought thousands of miles away from their homeland on American soil. On August 22nd, 2012 in Chicago gun violence broke out in eight different shootings, two of which were deadly. In 2012, a total of 351 shooting deaths in Chicago were tallied in August, reports attributing most of them to drug-gang violence (Keteyian 2012). The Drug Enforcement Administration Special Agent Officer of Chicago Jack Riley states, “We know that the majority of the narcotics here in Chicago, the cartels are responsible for. We know that the majority of the murders are gang-related so it is very clear to see the connection and the role.”

Riley has set up a 25-agency Strike Force consisting of State and Federal prosecutors, FBI, ATF, and Local Police. Their strategy is similar to that which Riley employed in El Paso Texas whose focus was to shut down choke points: where gang leadership meets with cartel lieutenants. “Daily turf battles over drugs and distribution are turning parts of this Midwest city into a Mexican border town.” states Riley. According to Keteyian, at least three major Mexican cartels are battling over control of billions of dollars of marijuana, cocaine and increasingly heroin in this city. That includes the ultra-violent Zetas and the powerful Sinaloa cartel, run by its leader Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman. Furthermore, this problem in Chicago is growing into a Midwest problem. These major cartel operations are spreading throughout the Midwest to Milwaukee, St. Louis, and Detroit (Keteyian 2012).

Despite the efforts and numbered successes the DEA has had on border control, other major members of the DEA can vouch for different experiences. Michael Braun, former chief of operations for the DEA mentioned a high-cost fenced territory on the Arizona border stating, “They erect this fence,” he said, “only to go out there a few days later and discover that these guys have a catapult, and they’re flinging hundred-pound bales of marijuana over to the other side.” He added, “We’ve got the best fence money can buy, and they counter us with a 2,500-year-old technology.”

Los Zetas also known as The Zetas Cartel is currently the largest drug Cartel in Mexico, located on the eastern coast around the Gulf of Mexico and operating in over half of Mexico’s states. The Zetas cartel is reportedly known for multiple violent crimes against both rival cartel members as well as its own. Miguel Angel Trevino Morales is thought to be the current leader of the Zetas. Trevino is known for holding “meetings” in which people do not return from. Trevino is also infamous for putting people in oil drums and setting them on fire, referred to as “human cookouts” (Richardson 2012). The Sinaloa cartel is the Zetas greatest rival and competition for turf, product, and profit though the Beltran and Tijuana cartels are allies to the Zetas.

In August of 2011, two dozen gunmen associated with the Zetas burst into the Casino Royale in Monterrey Mexico doused it with gasoline and set it on fire killing 45 people and injuring twelve more. Survivors reported that the gunmen shouted for customers and employees to get out of the building appearing to be an attempt at robbing the casino, but many people dashed further into the building hiding from the attackers. For this reason, many died from the fire and smoke throughout the building. The state Attorney General Leon Garza stated that “Cartels often extort casinos and other business, threatening to attack them or burn them to the ground if they refuse to pay.” (Corcoran 2012). Large-scale robberies driven by drug rings such as this put hundreds of innocent people in danger and lead to tragic unnecessary deaths and injuries, sadly this was not the first.

Only a month prior to the Casino Royale attack in Monterrey, gunmen killed 20 people at a local bar with assault rifles. Local authorities later found bags of drugs at the bar. In just the months of July and August 65 civilian deaths were accounted for in Monterrey. The city has been a turf battleground between the Zetas and Gulf cartels with deaths doubling from the prior year and tripling the year before that (Corcoran 2012).

The second major cartel in Mexico is known as the Sinaloa Cartel which operates in northwestern Mexico, south of the states of California and Arizona. Reportedly, the Sinaloa operates in over a dozen countries transporting illicit drugs from South and Central America to Mexico and the United States. Joaquin Guzman is the leader of this cartel and is Mexico’s most-wanted drug lord. Guzman escaped from prison in a laundry truck back in 2001. Today his cartel is responsible for some of the most violent and corrupt courses of action displayed in Mexico.

In May 2012, gruesome massacres took place in Nuevo Laredo Mexico, a city on the northeastern border of Mexico and Texas. The bodies of 23 people were found decapitated or hanging from the international bridge. Later discovery of 14 human heads placed in coolers near city hall were found. Authorities believe the Sinaloa cartel to be responsible for the massacre because a message was also hanging from the overpass directed towards the Gulf cartel from the eastern coast stating: “This is how I will finish all the fools you send.” This was thought to be in response to a car bomb perceived to have been set off by the Gulf cartel the week before (Guardian 2012). What would drive a movement to be so severe and brutal? How is it that these drug lords seem to lose sight of things to the point of massacring their fellow countrymen?

Chabat offers that another problem of the Mexican-American drug war is that the top three illicit substances come from or through Mexico; with 70% of marijuana, 25% of heroin, and 60% of cocaine being imported by the United States from Mexico. (Chabat 2002). These numbers show the high supply and demand ratio between the two countries and allude to the incentive for those involved in the black market. The severity of corruption within the law and the costs of lives it brings about.

From 1997 to 2000 there were 3,060 law enforcement officers suspended for corruption, meaning anything from buying, selling, holding, or simply overlooking narcotic traffickers. Moreover the issues of inefficiency, disappearing narcotics, escaped convicts and drug lords, money laundering etc.

Chabat offers four solutions or options to overcoming the war on drugs in Mexico and for the United States. One is to keep the war as it is, another is to come down even harder as a “total war” on drugs, forcing traffickers to other territories, a third is to lighten the war, though U.S. pressures tend to make this option difficult, and his fourth is to decriminalize or even legalize the narcotics.

Chabat’s main assumption is that the Mexican-American drug war isn’t working very well, and that both governments should collaborate together in order to come to a better approach to this market. He feels that the drug war and corruption have reduced Mexico’s guarantee of national and international security and therefore is subject to more pressure from the U.S. to fight organized crime. It is a vicious cycle, and radical modification of decriminalizing or even legalizing illicit substances in both countries would eliminate a great number of drug-war problems. Chabat admits that the war is not successful and will continue to have the same results if nothing is changed.

In Angela Gilliam’s “Toward a New Direction in the Media ‘War’ Against Drugs”, Gilliam discusses the “down river” market of drugs in the United States and who is selling and who is purchasing them, as well as, how the media portrays this. Gilliam suggests that “the rise in the drug trade is a direct result of a crisis in capitalism”. Wall Street estimated that “narco-dollars” revenue and annual $200 billion dollars, while a Texas State Department document estimated a $300 billion annual revenue. Regardless of which figure is more accurate, the drug market is clearly a big one (Gilliam 1992).

Much of the United States cocaine distribution and use is done by white Americans contrary to what the media may have you think. It is an estimated 80 percent of all American cocaine distribution and consumption according to Gilliam. The author goes on to discuss that minorities generally are “middle-men” living in poor communities and housing selling and distributing to people living in suburbs and nicer areas. The argument is that buyers and consumers of illicit substances are less likely to be arrested or charged than the distributors. Aside from what goes on in the communities, the United States is still the world’s largest market for illicit substances.

With the violent crimes committed amidst gangs and cartels via robberies and money laundering, law enforcement corruption and loss of men and women protecting the community, and the financial toll of agencies employment of patrol operations and equipment, decriminalizing or legalizing illicit substances of demand would eliminate the costs and tragedies of the current drug war.

Kleiman, Mark

2011 Surgical Strikes in the Drug Wars; Smarter Policies for Both Sides of the Border.

Foreign Affairs: Council on Foreign Relations

Rawlins, Aimee

2011 Mexico’s Drug War. www.cfr.org/mexico/mexicos-drug-war Council on Foreign Relations

Patrick, Stewart M.

2012 The War on Drugs: Time for an Honest Conversation. The Internationalist: Council on

Foreign Relations

Jelsma, Martin, Nadelmann, Ethan, Trace, Mike, and Wodak, Dr. Alex

2011 War On Drugs. Report of the Global Commission on Drug Policy. United Nations.

Campbell, Howard

2009 Drug War Zone: Frontline Dispatches from the Streets of El Paso and Juarez.

The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology. University of Texas Press

Gilliam, Angela

1992 Transforming Anthropology. Toward a New Direction in the Media “War” Against Drugs.

American Anthropological Association

Wilkinson, Tracy

2012 Mexico Under Siege. Mexico Government Sought to Withhold Drug Statistics. Los

Angeles Times

Araujo, Roberto

2001 The Drug Trade, the Black Economy, and Society in Western Amazonia. International

Social Science Journal 53.3 (Sep 2001): 451-457

Kleiman, Mark

1992 Neither Prohibition nor Legalization: Grudging Toleration in Drug Control Policy.

Daedalus 121.3 (Jul 1992): 53-83

http://www.justice.gov/dea/about/history/1970-1975.pdf

Stossel, John

2012 No They Can’t: Why Government Fails – But Individuals Succeed.

Threshold Editions (April 2012): 213-232

Richardson, Clare

2012 Mexcio’s Drug Cartels: Which Groups Are Running The Show? (August 2012)

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/08/28/mexico-drug-cartels_n_1831821.html

Drug War is a disaster! @durdyg check out my post and personal experience on the border:

https://steemit.com/commentary/@mikeinfla/getting-robbed-pressure-gradients-and-donald-trumps-wall

Indeed it is. Will do! Do you @mikeinfla have any idea as to why the article icon does not appear when I paste the link? It currently only displays the Steemit logo...

I have image link problems too. Haven't figured it out yet

Well, there is a good reason why certain illicit drugs are illegal. Crimes are committed too by drug users in order to fuel their drug addictions, also certain drugs can make you quite aggressive and potentially kill someone out of rage.

Congratulations @durdyg! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Congratulations @durdyg! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!