The Fall of Drexel Burnham Lambert

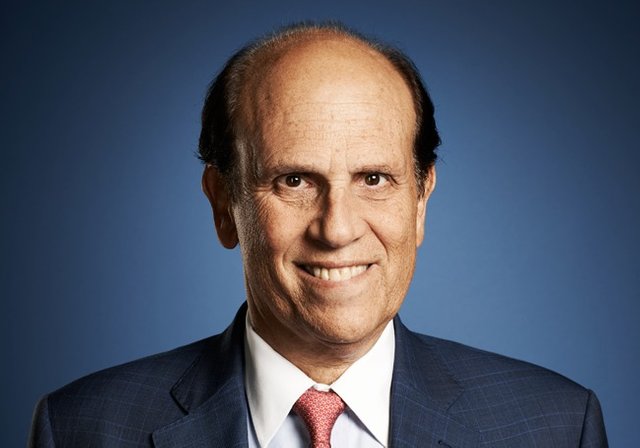

See this guy?

He was indicted on federal racketeering charges on March 30, 1989 and later pled guilty to 6 lesser felonies.

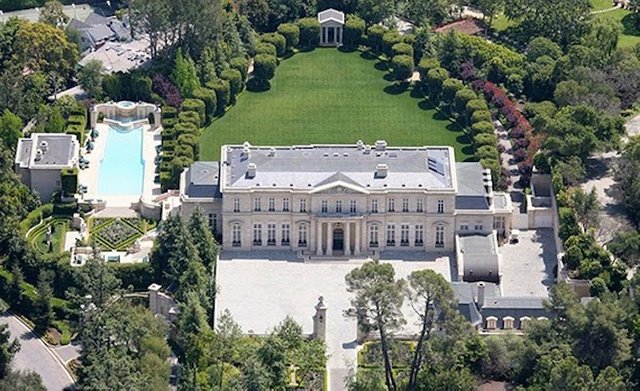

This is his house today.

Who is this man who went from riches to prison and back again?

His name is Michael Milken, and he was an executive in the now-defunct investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert.

What is an investment bank?

An investment bank is a large comporation that creates securities and sells them to private citizens and corporations.

Often these securities take the form of corporate or municipal bonds.

A bond a company or municipality's promise to pay back a loan with interest.

Investment banks normally market these bonds to investors at market prices and make sure they are compliant with SEC regulation.

What Drexel Was Doing

Drexel Burnham Lambert tried to differentiate itself as the bank that could raise the most loan capital regardless of its client's ability to repay the bonds.

Under the leadership of Michael Milken, Drexel marketed unpayable "junk bonds" to investors to raise huge amounts of capital for small companies that shouldn't have been borrowing so much money. To offset the risk of default, they also put a very high interest rate on the bonds, so that investors would reap heavy rewards if the company stayed solvent.

Later, other investment banks followed suit for fear of losing business, and the "high-yield department" of major banks became a centerpiece of bustling market activity. Investors believed that they could make more money buying high yield bonds because of the high interest rate.

The Crash

Soon enough, the debtor corporations began defaulting, triggering an economic crash.

Some insurance companies that had agreed to insure high-yield bonds went bankrupt.

As a result of the crisis, government investigators began looking at whether the risk of junk bonds had been properly reported.

They found that the investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert had pioneered the junk bond market without properly informing investors of the risk of these bonds.

Furthermore, they uncovered that Michael Milken had been colluding with high-profile investors such as Ivan Boesky to conceal activities such as insider trading and hostile takeovers.

One example of Milken's wrongdoing was "conspiring to conceal the true owner of a stock."

This violation sounds like a technicality, but it is actually more like terrorism.

Basically, Milken agreed to use his high position in Drexel to buy stock in certain companies anonymously for Ivan Boesky. Then, when his stake reached a majority voting share in the company, Boesky would threaten to shut the company down unless the board agreed to buy back his shares at a higher price.

By not reporting Boesky as the owner of the stock, Milken allowed Boesky to suddenly and without warning announce his takeover of the company, precluding the board of directors from taking countermeasures. The board was then helpless in the face of the threat, and had to pay Boesky.

Milken's schemes relating to manipulating the ownership of stocks and soliciting junk bonds amounted to 99 counts of racketeering, conspiracy, securities fraud, and insider trading charges, for which he plea bargained for 10 years in prison.

He was released in 3 years on parole.

Because many of Milken's fellow executives were complicit in the schemes, the government prepared racketeering charges against Drexel itself.

Because it would be bankrupted by billion dollar bail requirement, Drexel reached a plea agreement with prosecutors and after paying a fine of 650 million dollars was eventually sold to Morgan Stanley.