Philosophy Talk: George Perec's 'A Man Asleep' (1967) read through an Existentialist lens

Un Homme qui dort (1967) is the journey of a young twenty five year old man into apathy (Andrews; 1996 : 779): the protagonist (never named), does not attend his exam at university, avoids any communication with friends, abandons projects and preferences (Andrews 1996 : 779). He is an isolated individual who is cut off from substantive relations to others (Evans; 2009 : 74).

This research not only analyses Perec's character from a philosophical perspective, but will also consider Existentialism, a philosophy of the subject, rather than of the object, that does not offer any utopian solutions to the pathos of existence (Macquarrie 1972: 14, 265).

As in Existentialist philosophy, in Un Homme qui Dort (1968), man as an 'unhappy consciousness' is taken as the object of enquiry. In general, it is important to reconsider man as a fragmentary and fragmented creature who exists in a cosmos that is at once overpowering, threatening, and demanding (Natanson 1952: 366).

The reading of the novel has led me to compare it to various aspects of Sartre and his Existentialist philosophy.

Both Existentialism and Perec seem to analyse man’s being in the world. The main themes that will be taken into consideration throughout this paper are those of choice, responsibility and freedom.

Throughout these lines, two Existential themes can be observed: choice and freedom. According to Sartre, there are no eternal or a priori certitudes, no divine laws or salvation: man must create himself throughout his actions by choosing his ideals, meanings, and destiny (Natanson 1952). In essence, ‘l’homme est condamne’ à chaque instant a inventer l’homme’ (man is condemned to reinvent himself each instant) (Sartre 1946 : 38): that is to say man is constantly faced with the problem of having to choose himself and new values (therefore, make choices and actions) that will confer a certain meaning to his life and will make of him ‘ l’homme qu’il veut être, [..] l’image de l’homme tel [qu’il] estime qu’il doit être’ (he creates in his own image the man that he wants to be, i.e. his 'ideal' version of man' [...] (Sartre 1946 : 25, 38).

‘L’homme n’est rien d’autre que ce qu’il se fait’ (man is nothing but what he makes of himself) (1946, : 22); in this respect, the self constitutes itself through choice (Natanson; 1952 : 370): one is responsible of his own actions for they determine the self and all human beings (Sartre; 1946 : 24). In the same way, Perec’s character is perfectly conscious of what he is choosing; and further in the novel, he understands that the choices he has made will cause certain consequences in his life: ‘You won’t finish your degree, you won’t begin a postgraduate thesis. You will study no more. […] You are only twenty-five, but your path is already mapped out for you. The roles are prepared, and the labels’ (Perec; 1967 : 139, 155).

Man is obliged to live with this condition because as Perec states (1967 : 163) ‘you are alone’, there are no signs and there is no God that can guide man in taking the ‘right’ choices: he is fully responsible of his actions and also non-actions.

To be free means to be aware of this state of freedom, and that one is free in any case (Natanson 1952). In L’Existentialisme est un Humanisme (1946), Sartre writes it is impossible not to choose: 'si je ne choisis pas, je choisis encore' (even if I avoid choosing, I am nonetheless choosing) (Sartre 1946 : 73).

When the hero of Perec’s novel decides to stay in bed rather than to sit his exam, he states ’it’s not an action at all, but an absence of action, an action you do not perform, actions that you avoid performing’ (Perec 1967 : 138). He is perfectly right in underlining the fact that not performing an action is nevertheless making a choice; and in the character’s case it is a choice of indifference.

Responding to freedom with indifference is - according to Sartre - the unwillingness to recognise and accept the condition of freedom and responsibility. For this reason, man flees in mauvaise foi whenever he hides behind excuses (Bell 1993 : 92).

Furthermore, the research proposes a comparison between the protagonist of Un Homme qui dort and Kierkegaard’s aesthete, who pursues whatever activity that momentarily excites his curiosity and attention, avoiding commitment, responsibility and the development of a stable and consistent identity (Turnbull 2013: 53). In this perspective, the focus will be on the ‘disengaged modern self’ that stands out of tradition (Turnbull, 2013 : 53; citing Rudd, 2001 : 131, 138).

A comparison can be drawn between Perec’s hero and Kierkegaard’s aesthete: the latter is not in control of himself or his situation and does not seek to impose a coherent pattern in his life. Thus, the lack of continuity, focus or stability, incite him to commit to anything that is not permanent and definite (Gardiner 1988 : 44-45).

In the same way, Perec’s character simply wants to ‘wander and sleep, to be carried along by the crowds and the streets, to waste [his] time, to have no projects, feel no impatience, to be without desire, or resentment, or revolt’ (Perec 1967 : 161). The hero of the novel defines himself ‘a man of leisure, a sleepwalker, a mollusc’ that does not feel cut out for living or for doing, he only wants to go on and wait (Perec 1967 : 142).

Perec’s character says ‘it is on a day like this one, a little later, a little earlier, that you discover, without surprise, that something is wrong’ (Perec 1967 : 140). Clearly, the hero understands that he ‘no longer feel[s]’ and that his feeling of existence, of importance and of belonging to the world, is slowly slipping away (Perec 1976 : 140): his choice of indifference is leading his to ‘a life without motion, without crisis and without disorder, […] a life with no rough edges and no imbalance’ (Perec 1967 : 161). However he is starting his ‘vegetal existence’, his ‘cancelled life’ (Perec 1967 : 161). According to Kierkegaard, the sense of despair - that is a consequence of the aesthete’s choice of lifestyle - will lead the aesthete to desire a ‘higher’ form of existence, therefore to take the crucial step towards the ethical mode of existence (that will eventually take a subsequent step towards the religious mode of existence) (Gardiner 1988: 45).

The ‘metamorphosis’ of Perec’s character from aesthetic to ethical existence would presuppose his acceptance of his own state of being: a man alone in the world that is ready to suffer the everlasting categories of existence: anguish, dread, death, fear and aloneness (Natanson 1952).

Furthermore, in Un Homme qui dort (1967) Perec employs the second person pronoun ‘tu’, and as Roger Kleman (1967) suggested in a review on Perec’s novel ‘the second person of A Man Asleep is the grammatical form of absolute loneliness, of utter deprivation’ (Bellos 1989 : 10, 11). According to Graumann and Kallmeyer, the hero - having abandoned social relationships and social practices - ‘can no longer present himself as an individual, social human being, a je/moi’.

The author appears be employing the ‘tu'; form not only to dismiss all social contexts but also because he is unable to relate to himself (Graumann and Kallmeyer 2002 : 167). In essence, by using the ‘tu’ form, the narrator assumes the position of the observed and of the observer, the analyst and the analysed (Rybalka 1967 : 187).

However - according to Rybalka - by using this narration style, Perec avoids making his character live in an everlasting ‘mauvaise fois’: allowing him to attain lucidity in the last chapter of the novel: the feeling of tragic has faded away and his difficulty to be, has transformed in ‘necessite’ d’être’ (Rybalka 1968 : 587). ‘You are no longer the inaccessible, the limpid, the transparent one. You are afraid, you are waiting […] on Place de Clichy, for the rain to stop falling’ (Perec 1967 : 221).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andrews, C. (1996). Puzzles and Lists: Georges Perec's 'Un Homme qui dort'. MLN. 111(4), 775-796.

Bredel, U. (2002). ‘You can say you to yourself’: Establishing perspectives with personal pronouns. In: Graumman, C.F. and Kallmeyer, W. (2002). Perspective and Perspectivation in Discourse. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Bell, L. (1993) Boredom and the Yawn. In: Hoeller, K. (1993). Sartre and Psychology. New Jersey:

Humanities Press.

Editions POL (2012). Georges Perec - Jacques Chancel - 'radioscopie' - France Inter - 22 Septembre 1978. Soundcloud. Available from: https://soundcloud.com/editions-pol/georges-perec-jacques-chancel

Evans, S. C. (2009). Kierkegaard: an Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gardiner, P. (1988). Kierkegaard. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Macquarrie, J. (1972). Existentialism. England: Penguin Books Ltd.

Natanson, M. (1952). Jean-Paul Sartre’s philosophy of Freedom. Social research. 19 (3), 364 -380.

Perec, G. ( 1967). Things: a story of the sixties, with A Man Asleep. London: Vintage Books.

Rybalka, M. (1968). Un Homme qui dort by Georges Perec (Book review). The French Review. 41 (4), 586 -

Sartre, J.P. (1943). Being and Nothingness. [online] Available from: https://www.dhspriory.org/kenny/PhilTexts?Sartre?BeingAndNothingness.pdf

Sartre, J.P. (1946). L’Existentialisme est un humanisme. Paris: Editions Nagel.

Turnbull, J. (2013). Kierkegaard, Philosophy and Aestheticism. Filozofia 68. (1). P. 50.

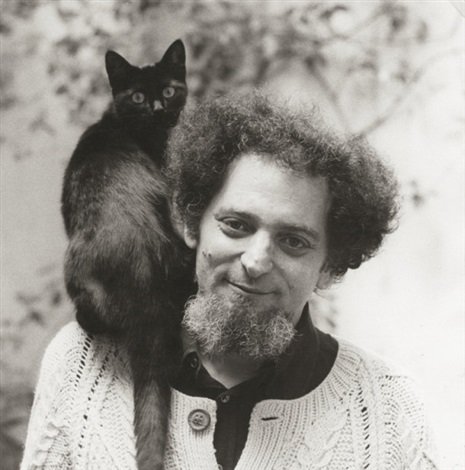

Image: Available from: http://www.artnet.com/artists/anne-de-brunhoff/georges-perec-h05vLW0kDzR22-IWy_oAIA2

You got a 2.39% upvote from @postpromoter courtesy of @francescap1995!

Want to promote your posts too? Check out the Steem Bot Tracker website for more info. If you would like to support the development of @postpromoter and the bot tracker please vote for @yabapmatt for witness!

Great Job Keep it up.

Thanks so much, glad you appreciate it :)