Where Do Thoughts Come From?

Thoughts come from learning. They originate from outside the self quite paradoxically. A baby has no thoughts, just feelings and sensations, like an animal. Only later in the child's development is he able to formulate any thoughts in his mind which are directly formed from his environment, mother and father, and so on.

So thoughts are from the past, from habits and routines and rituals we perform in our lifetimes. All thoughts are not bad or selfish in their own right; they are all inherently empty and without meaning. Thoughts originate from culture, media, and from other people you talk to.

Education or Intelligence?

Thoughts come from one's education and intelligence, or lack thereof. Of course the variety and quality of thought varies from person to person, but in general, many patterns of thought are predictable in sociological tests along demographic lines. So, in conclusion thoughts are collections of one's native words and simply come from one's learned knowledge of things.

So hence, the sharpest person has more highly evolved, specialized and complex thoughts as compared to the rather dull individual who has the most predictable, dismissive and mundane thoughts. So it is not as important where your thoughts come from as where your thoughts are going!

How Does Epistemology Help?

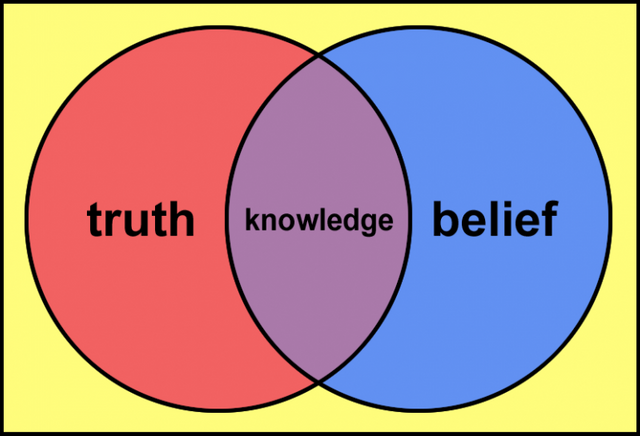

Epistemology, the branch of philosophy that studies the nature of knowledge and truth, explores questions like where do thoughts come from. Also, other questions, such as: What is knowledge? What does it mean for someone to "know" something? How much can we possibly know?

What's the difference between belief and knowledge, between knowledge and opinion, between knowledge and faith? How do we know that 2 + 2 = 4 or that the square root of 49 is 7? Says who, or what?

Is there an ultimate ground of knowledge, a world of absolutes? Do we know something from reason or from direct observation, or from a little of both? But no one can "observe" 2 + 2 =4, so how do we know that the statement (or formula) is true? What is truth? Is truth absolute or relative? What is the relationship between the observer and the observed, the knower and the known?

Is there an external world which we can make meaningful statements about and know? Is an object of knowledge a construction of mind? Is the world my idea of it, as philosopher Schopenhauer would say, or does it exist independently of all observers?

These are just some of the problems that epistemologists address.

Why is Epistemology Important?

Epistemology is important because it is fundamental to how we think. Without some means of understanding how we acquire knowledge, how we rely upon our senses, and how we develop concepts in our minds, we have no coherent path for our thinking.

A sound epistemology is necessary for the existence of sound thinking and reasoning — this is why so much philosophical literature can involve seemingly arcane discussions about the nature of knowledge.

Unfortunately, atheists who frequently debate questions that derive from differences in how people approach knowledge, aren't always familiar with this subject.

Socrates was one of the greatest educators who taught by asking questions and thus drawing out answers from his pupils ('ex duco', means to 'lead out', which is the root of 'education'). Sadly, he martyred himself by drinking hemlock rather than compromise his principles.

Bold, but not a good survival strategy; but then he lived very frugally and was known for his eccentricity. One of his pupils was Plato, who wrote much what we know of him.

Here are the six types of questions that Socrates asked his pupils; probably often to their initial annoyance but more often to their ultimate delight. He was a man of remarkable integrity and his story makes for marvelous reading.

The overall purpose of Socratic questioning, is to challenge accuracy and completeness of thinking in a way that acts to move people towards their ultimate goal.

Conceptual Clarification Questions:

Get them to think more about what exactly they are asking or thinking about. Prove the concepts behind their argument. Use basic 'tell me more' questions that get them to go deeper.

- Why are you saying that?

- What exactly does this mean?

- How does this relate to what we have been talking about?

- What is the nature of ...?

- What do we already know about this?

- Can you give me an example?

- Are you saying ... or ... ?

- Can you rephrase that, please?