electronic skin display shows your vital signs

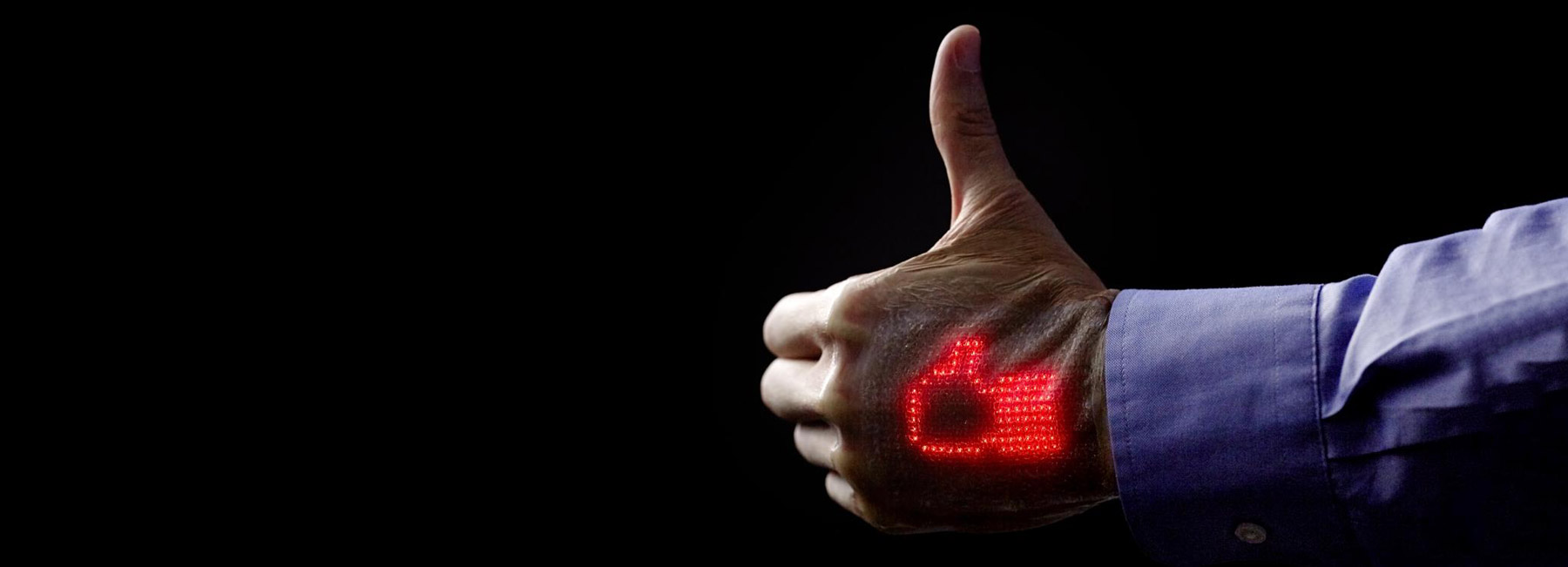

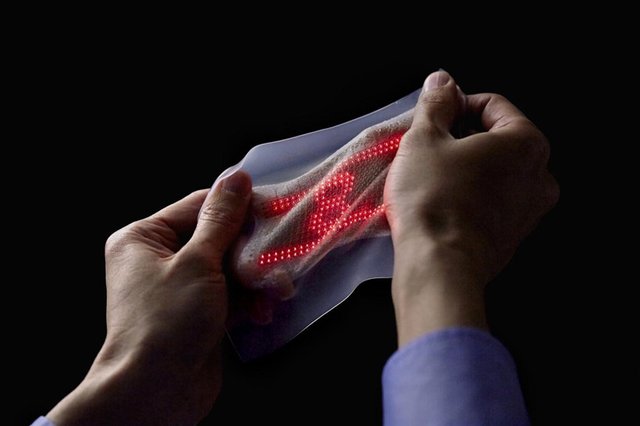

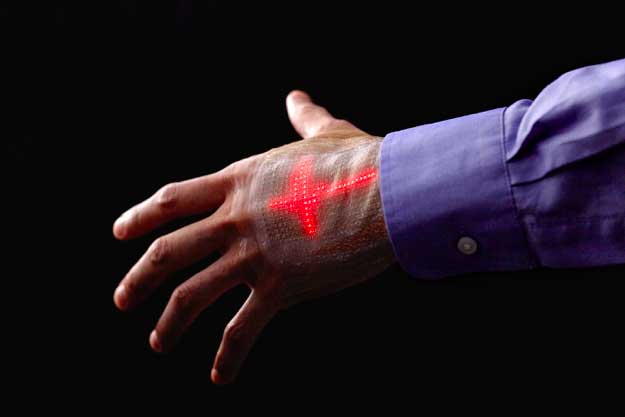

tokyo researchers have developed an e-skin that can measure and display vital signs like your heartbeat in real time. the stretchable skin is made up of a 16×24 LED display and is intended for use in healthcare.

engineering researchers at the university of tokyo have developed the ultrathin display which sticks to the skin. researchers say the rubber sheet will last for a week without causing inflammation.

the display is wirelessly connected to an electrocardiogram which can monitor the user’s heartbeat in realtime. those vital signs can then be transmitted to a healthcare cloud or device potentially for a doctor.

the device aims at easing the strain on home healthcare systems in ageing societies through continuous, non-invasive health monitoring and self-care at home. ‘the current aging society requires user-friendly wearable sensors for monitoring patient vitals in order to reduce the burden on patients and family members providing nursing care,’ the project’s lead, professor takao someya, said in a statement.

it is hoped the integrated skin display will be brought to market within the next three years but first need to improve the reliability of the stretchable devices by optimising its structure. dai nippon printing, a japanese printing company and collaborative partner, first need to understand if the technology can be scaled up in production and in size, e.g. for large-are coverage.

Please use the sharing tools found via the email icon at the top of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email [email protected] to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found at https://www.ft.com/tour.

https://www.ft.com/content/24bc6eee-14c3-11e8-9376-4a6390addb44

Electronic “smart skin” devices are being developed to monitor the biochemistry of sweating sports players, the health of stroke patients and the heartbeat of sick babies, researchers told the American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in Austin.

John Rogers, professor of materials science and engineering at Northwestern University, Chicago, described a suite of ultra-thin new stretchable and flexible sensors that stick directly to the skin and move with it.

“Stretchable electronics allow us to see what is going on inside people’s bodies at a level traditional wearables simply cannot achieve,” said Prof Rogers.

One device, which the Seattle Mariners baseball team will use during their spring training sessions, measures sweat emerging from the skin to determine how the body responds to exercise. It is also being tested on active duty pilots by the US Air Force.

Sweat percolates through the device’s microscopic channels and into different compartments, where chemical reactions result in visible colour changes, as concentrations of electrolytes and proteins in the sweat vary with exercise.

“Most people want to know if they are losing a lot of chloride, a little bit, or almost none,” Prof Rogers said. “They can just eyeball the device and determine if their electrolyte levels are high, medium, or low.”

Another stretchable device from the Northwestern lab is worn on the throat by stroke patients undergoing rehabilitation at home, to measure swallowing ability and speech patterns. These devices detect vibrations of the vocal cords, Prof Rogers said.

“They only work when worn directly on the throat, which is a very sensitive area of the skin. We developed novel materials for this sensor that bend and stretch with the body, minimising discomfort to the patients.”

Data from the throat sensors are transmitted wirelessly to an electronic dashboard, which alerts patients when they are underperforming on a particular metric.

The AAAS meeting also heard from a team led by Takao Someya, engineering professor at the University of Tokyo. The Japanese electronic skin can display the moving waveform of someone’s heartbeat. “Our skin display exhibits simple graphics with motion,” said Prof Someya. “Because it is made from thin and soft materials, it can be deformed freely.” It is stretchable by up to 45 per cent of its original length.

One application of the device might be to monitor sick babies. “Visualise a mother gently touching her baby’s forehead,” said Prof Someya. “A monitor can already look at body temperature accurately and the result can be read on a smartphone.”

He envisages, instead, reading the data by tapping a wearable electronic device on the baby’s skin, which will then display body temperature and other vital information. “What do you think the baby would prefer?” Prof Someya asked. “A mother’s touch means more to a baby. It conveys a mother’s caring.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.ft.com/content/24bc6eee-14c3-11e8-9376-4a6390addb44