A Declaration of Independence for the Oppressed: The Mid-European Union at Independence Hall

A Remarkably-Timed Celebration

Although the Great War would not end for another three weeks, and much of the city was laid low with the deadly Spanish influenza epidemic, for some the mood in Center City Philadelphia was jubilant on October 26, 1918. Great fanfare accompanied a highly-publicized meeting of “representatives from eleven oppressed nationalities of Central Europe” to sign a Declaration of Common Aims at the city’s fabled bastion of democracy, Independence Hall. [1] Children tolled a replica Liberty Bell, local politicians glad-handed the crowd, and various national flags waved in the breeze.

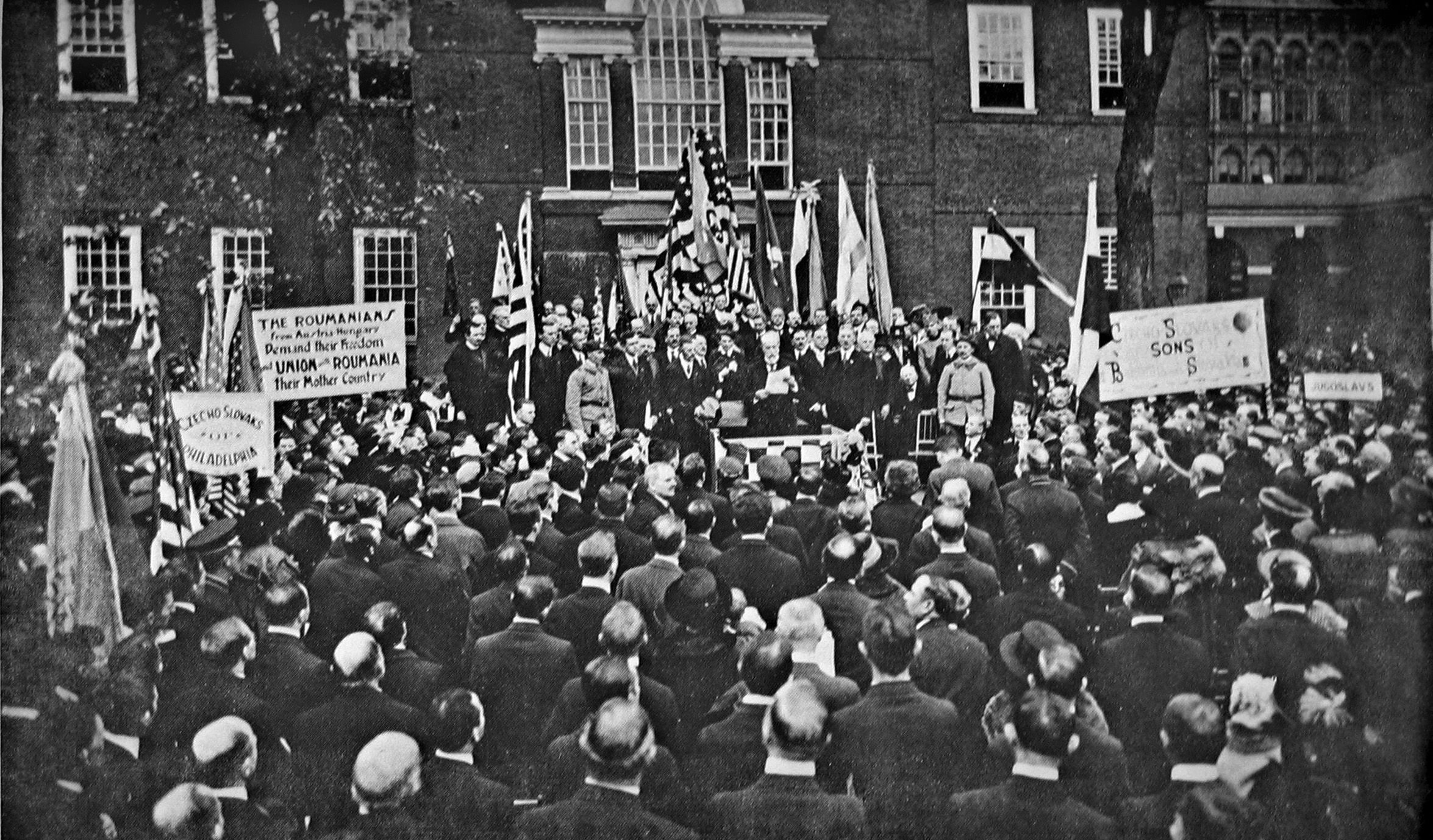

A crowd gathered in Independence Park listens as Tomáš Masaryk speaks, October 26, 1918. Source

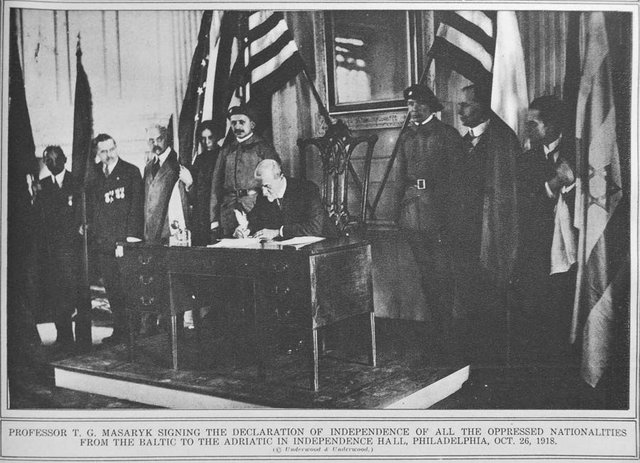

This symbolic and showy celebration was orchestrated by members of the newly-formed Mid-European Union, a political organization created to promote national self-determination of the Balkan states. The “historic document” to be signed was touted as a latter-day declaration of independence for Czechoslovaks, Yugoslavs, Poles, Romanians, Ukrainians, Albanians, Armenians, Italians, Zionists, Ruthenes, Lithuanians, and Greek nationalists; an “overthrow of the Hapsburg and Hohenzollern yoke by the long-oppressed peoples of Middle Europe.” [2] The tall figure of Czech politician Tomáš Masaryk, serving as chairman of the Union, projected “calmness, strength, and intellect. Whenever he spoke, the pencils of the reporters got busy.” [3]

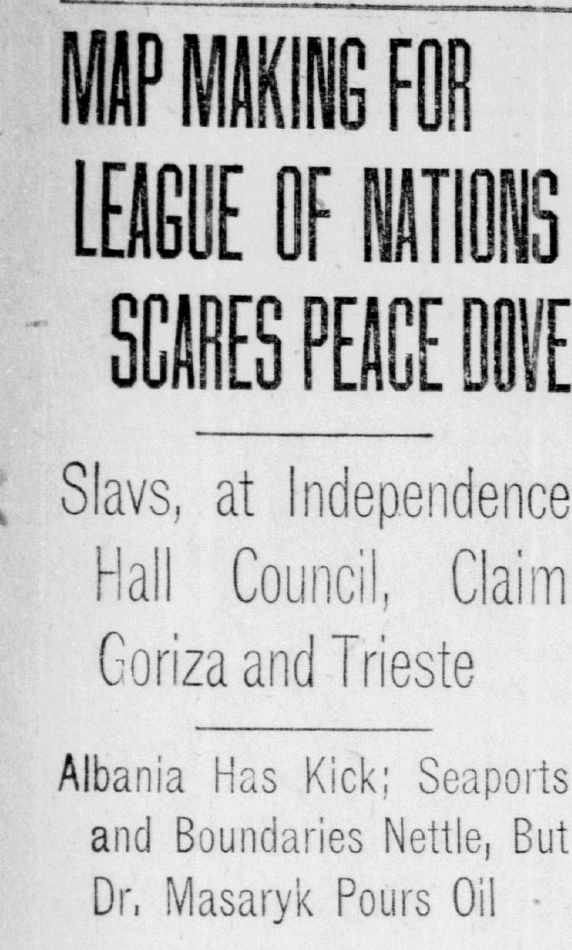

Philadelphia Inquirer, October 26, 1918

Scaring the Peace Dove

Philadelphia Inquirer, October 26, 1918

Behind this carefully-arranged façade of democratic cooperation lay considerable upheaval. The representatives and delegates present at the event claimed to represent 65,000,000 residents of the Balkan region, but in reality were of mixed influence; “Some of the delegates represented a recognized government with full power to bind it, others spoke for the principal revolutionary organizations of their people, but lacked authority to conclude anything binding on behalf of their organizations; while still other delegates represented only the principal national organizations of their people in the United States.” [3] Even so, they argued bitterly over territorial boundaries, missteps in translation, and bone-deep personal antagonisms. At one point, Yugoslav representative Hinko Hinković was reported to have torn up a map that awarded Dalmatian territory to the Italians, insisting “We will not tolerate any oppressor.” [4, p. 484]

In the end, many of the disagreements went unremediated. Representatives nevertheless posed for dramatic photographs and retired to a posh luncheon at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel at 200 South Broad St., where they were praised by John Wanamaker and serenaded with Czechoslovak folk songs. [3][4, p. 473] Contemporary observers meditated on the day’s potential importance: “The future only will show whether the declaration of October 26, 1918, will take its place in history as a document of equal, if not even greater importance, than the declaration of July 4.” [3]

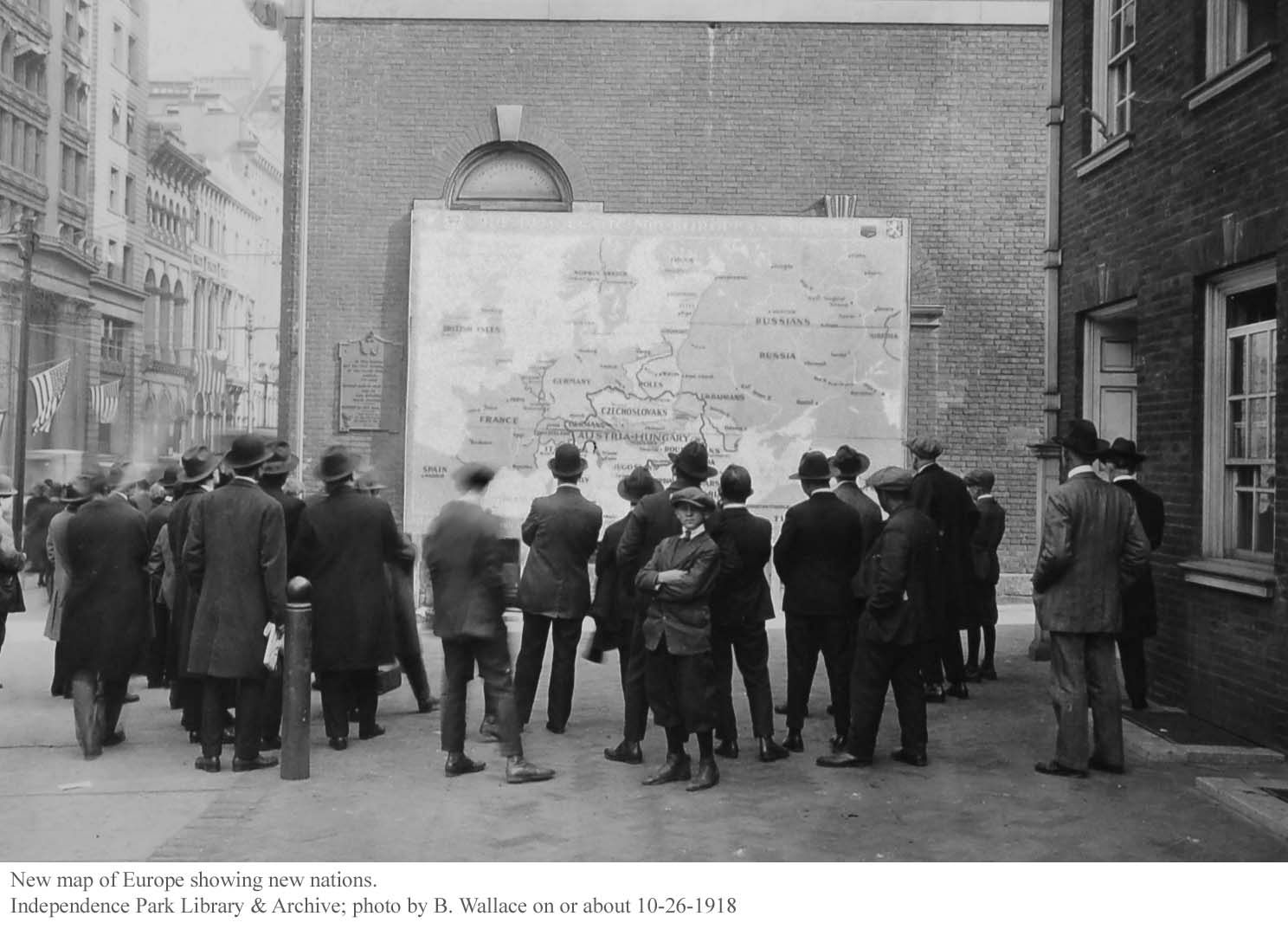

Source

So what happened to the Mid-European Union?

Despite the pomp and circumstance, the Declaration of Common Aims did not bear any real diplomatic fruit. The armistice that ended the Great War was signed on November 11, 1918, and just three days later, the Union chairman Tomáš Masaryk was elected President of the Czechoslovak Republic. Henceforth Masaryk was preoccupied and unable to soothe the tensions between representatives as he once had. Polish and Yugoslav delegates resigned from the Union, and the group’s priorities shifted. As soon as November 26, “the objectives of the Union were now described as designed to aid oppressed nationalities in central Europe and Asia Minor in winning their freedom; to dis-seminate information on the just demands of these nationalities, to exert pressure at the peace conference to realize these ends, and ensure mutual cooperation in the tasks of reconstruction.” [4, p. 488] But even these vague activities had petered out by the time the Paris Peace Conference negotiations commenced in summer of 1919.

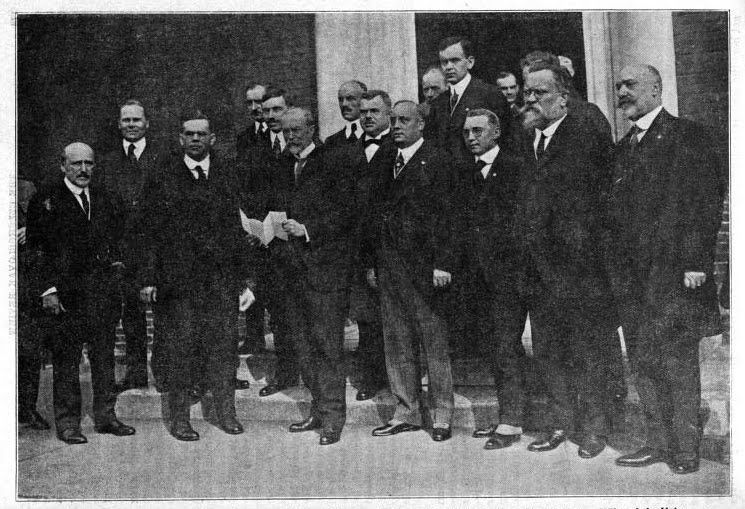

Mid-European Union representatives pose with Philadelphia Mayor Thomas B. Smith. Source

Although the Mid-European Union was a bust, the Philadelphia meeting on October 26 made an impact on local interest in the issues of Central Europeans. The event attempted to couch immigrant support of ancestral nations in the terms and trappings of the most American of events, and it was wildly successful in this effort. President Woodrow Wilson sent his approval, and politicians, businessmen, and local celebrities turned up to show their support of the dramatic gesture, even against the threat of the influenza epidemic which kept many Philadelphians inside their homes. In this moment of fervent Americanism, frequently wielded against the city’s foreign-born populations, it was not only acceptable but laudable to support one’s homeland and celebrate its folk traditions. In this sense, the day is notable, even if the Declaration of Common Aims signed that day is not remembered “as a document of equal, if not even greater importance, than the declaration of July 4.” [3]

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.

1. North, Simon Newton Dexter, Francis Graham Wickware, and Albert Bushnell Hart, eds. The American Year Book (1918).

2. “Map Making for League of Nations Scares Peace Dove.” Philadelphia Inquirer (Oct. 26, 1918)

3. “The Philadelphia Convention.” The Czechoslovak Review 2:10 (Nov., 1918), 176-178.

4. May, Arthur J. “H.A. Miller and the Mid-European Union of 1918.” The American Slavic and East European Review 16:4 (Dec., 1957), 473-488. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3000774

This is super neat! Do you know if the Union had similar gatherings in other American cities?

They did! They had a rally in New York and brought the fake Liberty Bell with them to Chicago. Somehow, even after the Union fell apart, it ended up in Prague.

Wow, informative and interesting. I knew that Korean Independence activists met in Philadelphia in 1919 but I had no idea about the Mid-European Union. Cool how Philadelphia has an international significance for such movements.

Thanks, and agreed! A book waiting to be written, perhaps...

Yo cool! I literally know nothing about this a'tall. Do you know if there are any projects/visualizations/articles that detail all of the different organizations who have led rallies at Independence Hall? I think it'd be a really interesting data web or story map or something trendy like that.

I don't know of any. I think it would be fascinating, though! Like, how many fake Liberty Bells are floating around this planet?!