A "Self-Sufficient" Institution: Peonage at Pennhurst in 1918

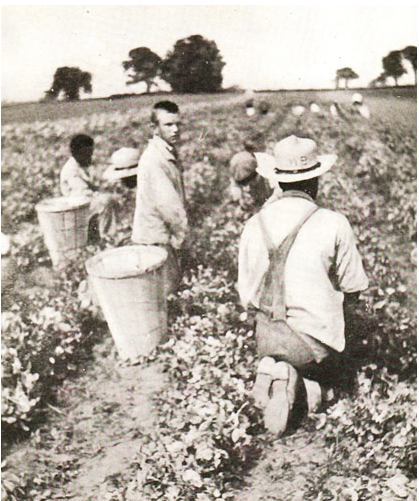

- "Picking Peas, 1918 Trustees Report," Photo used with permission from the Pennhurst Memorial & Preservation Alliance. http://www.preservepennhurst.org/default.aspx?pg=21&ssgrp=64&ssitem=24.

In 1903, the Pennsylvania State Legislature authorized the founding of the Eastern State Institution for the Feeble-Minded and Epileptic, then the second state-run institution for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. The Eastern State Institution later became known as the Pennhurst State School and Hospital. Pennhurst accepted its first resident on September 23, 1908. A decade later, 1918 proved an eventful year at the institution. For the purposes of this post, however, we will focus on how Pennhurst profited from its resident’s labor, also known as peonage.

Peonage is as a system whereby an employer compels another person to pay off a debt through labor. It is also known as debt slavery or debt servitude. After the end of the Civil War in 1865, peonage was outlawed by Congress in 1867, but after Reconstruction, African Americans in the South often found themselves swept into peonage by various means, and the system itself was not ended fully until the 1940s. For the residents of Pennhurst, peonage was not a matter of indebtedness, but rather a means for the institution to be self-sufficient. The bulk of the food served at Pennhurst in 1918 was grown on the grounds which added up to several hundred acres of land. Insufficient funding at state-run institutions was notorious, and by producing food for their residents, the Pennhurst leadership managed to save a significant sum of money. Something else that was beneficial in saving money? Not paying the residents who worked in their fields.

- "Collecting Hay, 1918," Photo used with permission from the Pennhurst Memorial & Preservation Alliance. http://www.preservepennhurst.org/default.aspx?pg=21&ssgrp=64&ssitem=22.

None of Pennhurst’s residents who contributed this manual labor earned any wages. Their labor was considered “training.” But training for what? Not only were jobs like picking peas vanishing for laborers, but per the American eugenics movement these residents were meant to stay segregated from the rest of society indefinitely. In fact, between 1904 and 1921, the rate of institutionalization for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities nearly tripled in the United States.

As increasing numbers of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities were sent away to institutions like Pennhurst around 1918, institutions like Pennhurst continued to profit off of their manual labor until the practice was permanently outlawed in institutions in 1973, when in the Souder v. Brennan case the Supreme Court asserted that the “minimum wage and overtime compensation provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act apply to persons residing in state-operated facilities for persons with mental retardation and mental illness who provide work that would otherwise be done by paid employees.” Curiously enough, the following year, 1974, saw the filing of the Halderman v. Pennhurst Case which would move through the courts for another decade before a final settlement would be reached in 1984 calling for the institution’s final and permanent closure.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more click here.

Sources:

Pennhurst Memorial & Preservation Alliance, “Pennhurst Timeline,” Pennhurst Memorial & Preservation Alliance, 2015. http://www.preservepennhurst.org/default.aspx?pg=93. (Accessed 1/19/18).

Nancy O’Brian Wagner, “Slavery v. Peonage,” Slavery By Another Name, 2012. http://www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/themes/peonage/. (Accessed 1/19/18).

Pennhurst Memorial & Preservation Alliance, “Collecting Hay, 1918,” in the Pennhurst Memorial & Preservation Alliance Archives. http://www.preservepennhurst.org/default.aspx?pg=21&ssgrp=64&ssitem=22. (Accessed 1/19/18).

Pennhurst Memorial & Preservation Alliance, “Picking Peas, 1918 Trustees Report,” in the Pennhurst Memorial & Preservation Alliance Archives. http://www.preservepennhurst.org/default.aspx?pg=21&ssgrp=64&ssitem=24. (Accessed 1/19/18).

Andrea DenHoed, “The Forgotten Lessons of the American Eugenics Movement,” The New Yorker, April 27, 2016. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-forgotten-lessons-of-the-american-eugenics-movement. (Accessed 1/19/18).

Pennhurst Memorial & Preservation Alliance, “Pennhurst Timeline,” Pennhurst Memorial & Preservation Alliance, 2015. http://www.preservepennhurst.org/default.aspx?pg=93. (Accessed 1/19/18).

Yikes, how terrible- and not unlike the "invisible labor" employed today in prisons across the country. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

I agree completely. I think what upset me most as I read about it was how those running the institution seemed to feel as though this was a legitimate option for cutting costs. It's just one more example of the dehumanization people face when they're hidden away; whether that be in a prison or an institution for people with disabilities.

My thoughts exactly.

Really insightful post, Derek! It sounds like a prolonged struggle to grapple with the broader meaning of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Thanks John! As I was reading about peonage's broader history outside of institutions like Pennhurst I found myself thinking the same thing, especially having recently rewatched "13th."

Thanks for the deeper view into the Pennhurst story. I wonder where else peonage was common. And you mention it ended in the 1940s. Was there a drama (i.e. a good story) around it's demise?

Interesting to see the use of the word "training" as a way of extracting labor - it seems like one-hundred years later things haven't changed too much.