1918: A Transformative Year for Philadelphia

In 1918, the world was at war. While American doughboys fought in the trenches of Europe, the homefront experienced radical transformations. The booming war industry and a dearth of White workers attracted hundreds of thousands of southern Black migrants to Philadelphia where they enjoyed steady employment. Nearly 60,000 Philadelphians answered the call to fight during the war, but the city still lived up to its nickname “workshop of the world.” Cramps Shipyard, Hog Island, Baldwin Locomotives, and other industrial sites employed thousands of African Americans who recently migrated from the Jim Crow South.

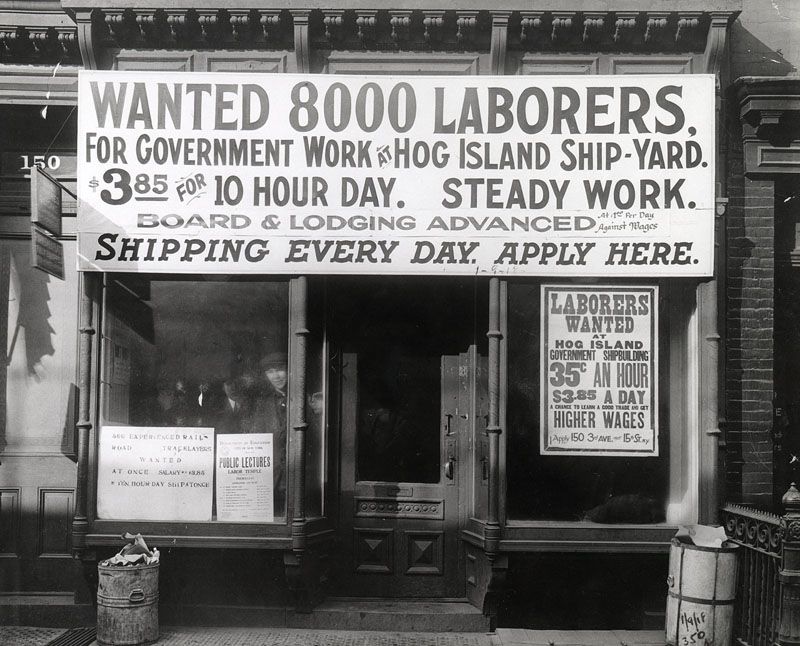

"Hog Island Help Wanted Sign," circa 1918.

These southern migrants, however, were not welcomed with open arms. Competition over housing and jobs caused resentment among the conservative White population who discriminated against the newcomers. Although many saw Philadelphia and other northern cities as a land of opportunity, they did not necessarily leave the bigotry and hatred behind in the South.

In November 1918 after the armistice ended the war, White Philadelphians returned home to a transformed city and competed with the new migrants for employment in the postwar recession. In an interview conducted by Charles Hardy, Milo Many, an “old Philadelphian” who witnessed the arrival of southern newcomers, discussed race relations following the war. He recalled an event that occurred outside his work at 31st and Chestnut streets.

“Where we were located, we could look over Walnut Street Bridge and Chestnut Street Bridge from West Philadelphia...we’d see Whites chasing Negroes, back over into West Philadelphia, and Negroes streaming on back down into South Philadelphia. An incident happened right in front of our building in which there was a pitched battle out there between Blacks and Whites.”– Milo Manly, September 11, 1984

[ ! [“Where we were located, we could look over Walnut Street Bridge and Chestnut Street Bridge from West Philadelphia...we’d see Whites chasing Negroes, back over into West Philadelphia, and Negroes streaming on back down into South Philadelphia. An incident happened right in front of our building in which there was a pitched battle out there between Blacks and Whites.”] (

Despite the racial intolerance that African Americans suffered, the Black population of Philadelphia continued to soar. In 1910, Philadelphia had one of the largest and oldest African-American communities, but the population substantially increased from approximately 85,000 to 220,000 in 1930. Southerners realized the potential of Philadelphia’s economy, and they cemented themselves in the fabric of the city.

Although many consider 1918 an end date thanks to the conclusion of World War One, it was also a transformative year. The consistent race riots made Black Philadelphians realize the need to mobilize and assert their strength in numbers. Organizations like the N.A.A.C.P., Armstrong Association, local churches, and the Philadelphia Tribune remained active throughout the following decades and vocalized the struggle of Philadelphia’s African Americans. Following the war, Philadelphia not only established an even larger African-American community, but it also developed perhaps the most mobilized Black populations.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more click here.

Resources:

Goin' North: Tales from the First Great Migration to Philadelphia.

Jacob Downs, "World War I," The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, 2014

Prof. Hardy's work from the '80s was groundbreaking. I remember it well. It is interesting (and unfortunate) that there still seems to be no major, active repository of oral history in the Philadelphia area.

The photo of the storefront is a great one, BTW. I see it is linked to its source, but Is it a disservice to not put that credit with the image?

I've been exploring Hardy's stuff all month, mining for good oral history clips for lesson plans. I've definitely procrastinated for hours inside that website...