Film review: the peculiar place of Chinese art film | The Assassin (2015)

This is a film review I wrote for my college newspaper. It is about The Assassin (2015), which won several international awards and a great many rave reviews from critics. I'd like to share this review with you all as a kickstarter to my film review series on Steemit. Enjoy :)

I remember when the Chinese film Black Coal, Thin Ice (2014) won the Golden Berlin Bear, mainland Chinese critics gave it universal acclaim. In the eyes of the Chinese mass audience, however, it was labeled as a yishu pian (艺术片), a slightly pejorative term close to the meaning “art film,” characterized by slow editing, terse dialogues, restrained acting, ambiguous story and unexciting long shots. Basically, a yishu pian, as an average Chinese audience sees it, is not Avengers or Furious 7. Still dominated by Hollywood pop films, mainland China’s film scene is still hostile to “art films,” unless, of course, that film won an important award, granting the film marketability.

Still of Black Coal, Thin Ice with Fan Liao and Lun-Mei Kwei

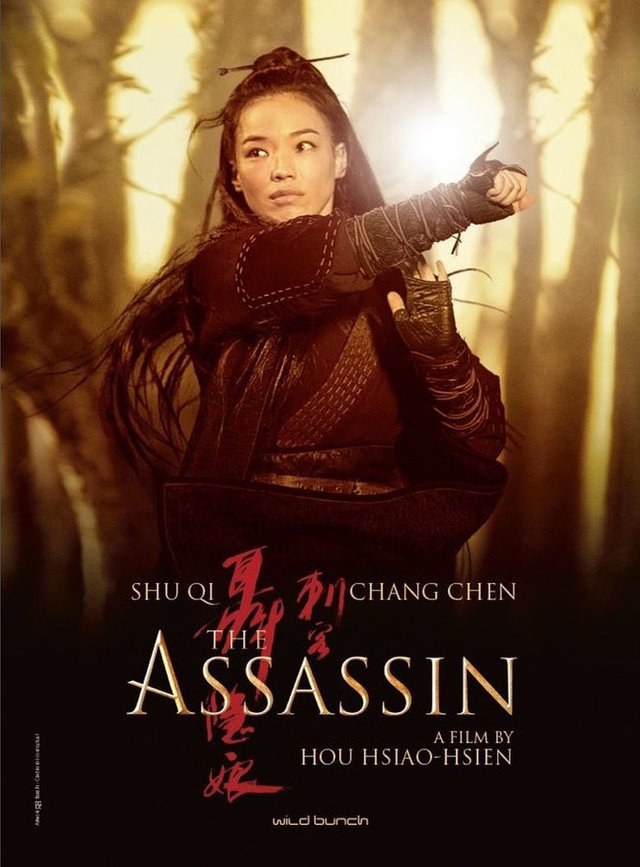

Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Wuxia entry The Assassin (2015), which won a Best Director at Cannes, is a yishu pian with marketability. The film was among the 2015 New York Film Festival selection, and had released in theaters in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan to critical acclaim. Hou’s signature slow-panning camera, long shot and authentic mise-en-scene accompanied the protagonist Nie Yinniang–played by Shu Qi–throughout her journey during the late Tang dynasty, circa 750 AD.

The Assassin film poster

Albeit a master of ruthless killing, Nie Yinniang voluntarily gave up on an assassination of a corrupt official, because, as she explained to her master Jia Xin, she couldn’t bear killing a father before his innocent child. Claiming to cleanse Nie Yinniang’s unprofessional compassion, Jia Xin sent her to assassinate her cousin and first love Tian Ji’an (played by Chang Chen), who was now the governor of her hometown Weibo. Her arrival, however, instigated a complicated plot of conspiracy among the big families in town, unfolding in the historical background of an evolving relationship between the military stronghold Weibo and the weakening Imperial Court of Tang dynasty. Nie Yinniang’s mission, at least in her own mind, was never so simple as killing her cousin. She would have to decide among family, love and her master’s teachings as she progresses through the perilous terrain of her hometown.

If anything stands out in the film, it is the incredibly slow pace. The slowness could be a gesture to authenticity, since the pre-modern Chinese life could hardly compare with the fast, discontinuous, compartmentalized postmodern life. To be alive in our time involves a constant seeking of sensorial stimulation, including browsing Facebook, listening to music while exercising, absorbing endless information and the cinema itself. Aided by special effects, quick editing and the constantly moving camera, the dominant cinema of our time appeals to our senses by assaulting them with sex, gore, split-second action and melodrama.

Hou’s “Assassin” offers an alternative. Nie Yinniang kills with elegant violence but without gore. Tian Ji’an’s subdued monologue expresses things deplete of melodrama. Sexual display in the film is minimal, if not nonexistent.

By resisting the dominant cinema, Hou assaults the very idea of assaulting the sensorial. His portrayal of the late Tang lifestyle is one that deliberately disappoints those who expect an action-driven, melodramatic Wuxia entry, and one that provides puzzles and thinking rather than distraction and entertainment.

And, consequently, Assassin becomes the black sheep in the Wuxia cannon. Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) combines exotically beautiful cinematography and quick, clever, and sometimes incredibly gravity-defying sword fight. Zhang Yimou’s Hero (2002) and House of Flying Daggers (2004) continues to mythicize a kind of independent martial-art warrior who flies on rooftops and usually combats in pristine and gorgeous landscapes. Wong Kai-war also made his mark with his Grandmaster (2013), which ventures further to turn the martial artist Ip Man into a superhuman “Neo” fighting hundreds of black suit “Agent Smith” in a bleak, heavily rainy night.

Tony Leung becomes the Neo in this fight scene in Grandmaster

Assassin does none of that. Hou deemphasizes fight scenes, which sometimes could only be seen from a distant shot. Make no mistake, Nie Yinniang does fly on rooftops and kills with elegance, but these features were not the eyeball-attractions like they were in previous renowned Wuxia films. As if Nie Yinniang themselves, these fight scenes come out of nowhere and, after the job is swiftly done, disappear. They do not linger, nor do they elaborate. The camera’s focus, or rather Hou’s vision, is on something more complicated, something Ang Lee and Zhang did not explore, for good reasons.

And one of them is the need to westernize. In an average Chinese audience’s mind, Crouching Tiger and House of Flying Daggers are not yishu pian. In another word, they are closer to Avengers and Furious 7 than Assassin. They might be quintessentially Chinese, but they are no less a spectacle, a Chinese version of the Cinema of Attractions.

The yishu pian aesthetic is very apparent in the film's pace, cinematography, and direction

Assassin loves richness of history and embraces familial ties so complicated that many Chinese audiences couldn’t decipher. It loves succinct fight scenes. It loves making the audience go through tediously long shot to see the minute changes of countenance that informs so much psychology beyond words. It loves placing symbolism that requires proficient understanding of pre-modern Chinese traditions. Above all, it loves resisting the dominant cinema and resisting the westernization of the Chinese cinema. Much like Nie Yinniang, Hou is a cinematic lone wolf. He sees, like Nie Yinniang sees, what is really happening behind the cinematic back doors and decides, like Nie Yinniang decides, to be true to his origin, rather than the “master’s teachings.”