O, By the By

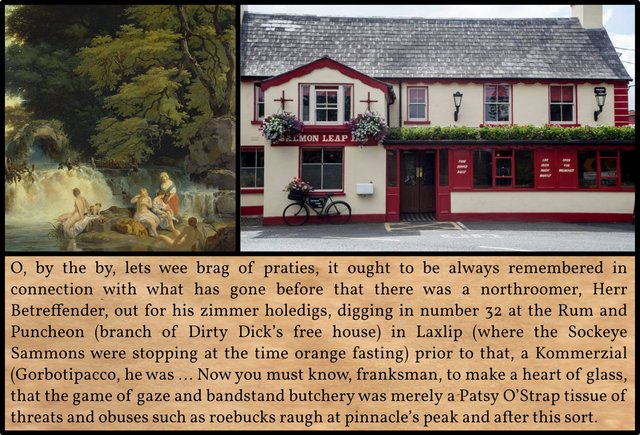

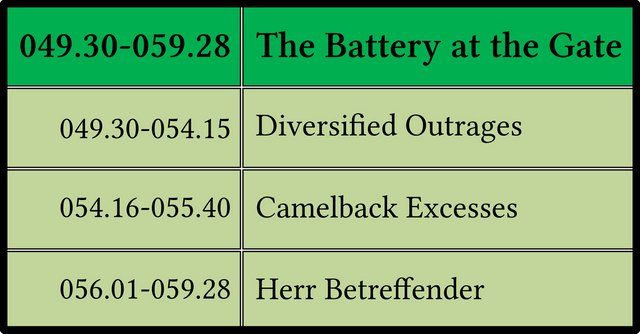

The last ten pages of Chapter 3 of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake comprise an episode known as The Battery at the Gate. This paragraph opens the third and final section of the Battery, Herr Betreffender (RFW 055.01–059.28), in which HCE suffers an assault at the hands of an Austrian salesman on his summer holidays. As usual, this is just another retelling of the same old story of HCE’s roadside encounter with the King, which was also retold as an encounter in the Phoenix Park with the Cad with a Pipe.

First-Draft Version

This paragraph began life as a pair of sentences in the middle of a long paragraph, which Joyce later expanded to fill more than four pages of The Restored Finnegans Wake (RFW 055.19–059.28). Herr Betreffender was originally an unnamed travelling salesman, who was staying as a guest at HCE’s tavern. He attacks the gate―the Battery at the Gate―believing that HCE has robbed him of some cash and rifled the pockets of his overcoat:

It ought to be always remembered that there was a commercial stopping in the hotel and he missed six pounds fifteen and he found his overcoat disturbed. The gate business was all threats & abuse. ―Hayman 74

These details were inspired, once again, by a story Joyce read in one of his favourite newspapers, the Connacht Tribune:

FOND OF FINERIES

Young Girl Returned for TrialAt Ballinasloe District Court on Saturday last, before Mr. J. H. Gallagher, D. J., was charged in custody with the alleged larceny of a purse containing 17s. 2d., and a pair of woolen gloves, the property of Miss Julia Burke, a teacher at the Convent of Mercy schools, Ballinasloe ... Some time ago there was a gentlemen living in the house where accused was a servant, and he missed £75 ... Miss Julia Burke’s deposition was to the effect that she was a teacher at the convent schools, and was in the classroom on November 14. Accused came there accompanied by a little girl. She said she had come for an overcoat belonging to a little girl of Mrs. Hills, Society St. She stated that the overcoat was left there by the child. Accused went into the classroom to get it and afterwards when she (Miss Burke) went in she found her coat, which was hanging on the wall, disturbed; the pocket lining was hanging out, and the purse and gloves were missing ... Mrs. Hill deposed that when her little son arrived from school he said he had left his coat behind, and she was about to send him back again when accused came into the shop and on hearing her sending the child back for his coat, she volunteered to go with him. ―Connacht Tribune 24 November 1923, Page 6, Column 3

Why did Joyce alter £75 to six pounds fifteen (£6 15/- = 135 shillings = 1620 pence)? The same amount recurs in the following chapter, disguised as six victolios fifteen (RFW 065.34). Numbers are usually important in Finnegans Wake―note the familiar 1132 in this paragraph―but if these particular figures hold any significance, I am not aware of it.

In revising this section, Joyce made the protagonist an Austrian journalist, with the result that the final version is heavy with German words and grammatical constructions. But why Austrian? Perhaps Joyce simply wanted an excuse to use the German word Betreffender (person concerned), from the verb betreffen, which means both to encounter and to concern. This word also connects HCE’s attacker with the mysterious fender that figured earlier in this chapter in another version of the assault on HCE, and identifies Herr Betreffender as both offender and defender. HCE is both the attacker and the attacked: he is his own worst enemy.

German Elements

The prominence of an Austrian salesman and journalist has resulted in lending this paragraph a distinctly German flavour:

- Betreffender German: Betreffender, person concerned

- German: betreffend, concerning, regarding : in question, relevant

- German: herbetreffend, aforementioned

zimmer holedigs summer holidays.

- German: Zimmer, room.

- Heinrich Zimmer: 19th century Celticist, author of Keltische Beiträge, a summary of which Joyce read : also his son, Indologist and linguist, author of Maya: Der Indische Mythos, which he sent to Joyce in 1938 with a dedication, and from which Joyce took some notes.

- hole, dig. Bill Cadbury discerned a nice entombment echo here.

- hole: small dingy lodgings

- digs: lodgings

Kommerzial German: Kommerzialrat, Councillor of Commerce―a title awarded on an honorary basis to members of the business community who have served the Republic of Austria in a professional capacity.

- commercial: commercial traveller, travelling salesman : tramp, vagrant

Gorbotipacco Italian: Corpo di Bacco, By Jove! As FWEET notes, the confusion between voiced and unvoiced consonants is typical of German mispronunciation of Italian.

wreaking German: rauchen, to smoke

Zentral Oylrubber German: Zentraleuropa, Central Europe

Osterich German: Österreich, Austria. The name means Eastern Kingdom. John Gordon suggests that ostrich may be included, evoking Australia (Southern Land). In Finnegans Wake Australia is an infernal underworld associated with Shem.

mark German: Mark, mark, a unit of currency

- German: Ostmark, Eastern March, the forerunner of Austria in the Middle Ages

Gosh these wholly romads This phrase possibly conceals a reference to the Goths and other German tribes, who roamed as nomads across eastern Europe and invaded the Roman Empire. The Holy Roman Empire of the Middle Ages is also meant.

Yuly German: Juli July : Jul, Yule, Christmastide

wheil German: weil, because

swishing German: zwischen, between

swopping Swiss German: Schwob, a German, a Swabian

myth German: mit, with

brockendootsch German: Der Brocken, The Brocken, the tallest peak in Germany’s Harz Mountains, and the scene of the Witches’ Sabbath (Walpurgisnacht) in Goethe’s Faust. It is also the site of the famous optical illusion known as the Brocken Spectre. The Scottish novelist James Hogg evokes the brocken spectre on Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh in his novel The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, which is alluded to on a number of occasions in Finnegans Wake.

- German: Brocken, morsel, crumb, fragment

- Heinrich von Kleist, Der zerbrochene Krug (The Broken Jug), an allegorical play about the Fall of Adam

- German: gebrochenes Deutsch, broken German

German: Der Fall Adams, The Case of Adam, The Adam Affair : The Fall of Adam

Frankofurto Siding German: Frankfurter Zeitung, Frankfurt Times, a German newspaper (see below)

Fastland German: Festland, Continent, Mainland (Europe). Fastland is the Danish form.

er German: er, he

constated German: konstatieren, to state : to establish, verify : to detect

that one had ... disturbed In German the past participle in such grammatical constructions is placed at the end of the clause, as here.

lammswolle German: Lammwolle lamb’s wool

and wider German: und weiter, and, further, moreover

- and wider ... other German: entweder ... oder, either ... or

- German: wieder, again

he might the same zurichschicken In German the infinitive in such constructions is placed at the end of the clause.

zurichschicken German: zurückschicken, to send back

- Zurich, where Joyce lived for several years.

he would ... become Another example of German grammar, in which the infinitive is thrown to the end of the clause.

tosend and obertosend German: tausend und abertausend, thousands and thousands

- German: tosen, to roar, to rage

tonnowatters, German: Donnerwetter!, Gosh! : thunderstorm

monkey’s damages German: Affenschande, crying shame (literally: monkey-shame)

- Artificial German: Affenschaden, monkey-damage

become German: bekommen, to get

and after this sort Literal translation of German: und nach dieser Art, and of this kind.

Michael Joyce

Was Herr Betreffender, contributor to the Frankfurter Zeitung, based on a real person? Adaline Glasheen believes that this is possibly the case:

*Betreffender, Herr (German “beforementioned”)―probably refers to Michael Joyce, English writer whose story Vielleicht ein Traum [Perchance a Dream] appeared in the Frankfurter Zeitung, 19 July 1931, and was attributed to James Joyce, who was pretty mad about it. See Letters, III, 224–32. ―Glasheen 30

In Letters III, we read Richard Ellmann’s footnote and translation of Joyce’s first letter about this story. The latter was in French and addressed to the poet Yvan Goll, whom Joyce had first met in Zurich:

The Frankfurter Zeitung published on 19 July 1931 a translation by Irene Kafka of a story, ‛Perchance a Dream,’ by Michael Joyce, originally published in the London Mercury. The newspaper attributed it to James instead of Michael Joyce, and to James Joyce the ‛error’ appeared disingenuous ...

‛Dear Mr Goll: We have kept the postal receipt for the disc sent by registered mail. It has probably been stopped by the censorship and it is useless to send another. Now in Frankfurt, too, the Frankfurter Zeitung of 19 July has published a whole page of text by J. J., author of Ulysses, translated from the English manuscript by Irene Kafka. Who can she be ? Where has she found this manuscript which the newspaper attributes to me? I know nothing of it. I do not know her at all. I never wrote that silly story which is called Vielleicht ein Traum. I have never communicated with the Frankfurter Zeitung. Perchance a Dream but definitely an outrage. >Cordially yours

James Joyce’ ―Letters III 30 July 1931 (Ellmann III:224)

Although Joyce had already made HCE’s attacker an Austrian commercial by June 1927, when a version of this chapter appeared in transition, the name Herr Betreffender and the references to the Frankfurter Zeitung date from the early 1930s, so Glasheen is probably correct in her analysis (JJDA).

I will conclude by quoting a lengthy paragraph from an article on this affair by David Spurr, Professor Emeritus of Modern English Literature at the University of Geneva:

An example of the latter tendency [to querulous paranoia] in Joyce’s life as a writer emerges from his response to the publication in 1931 of a short story entitled “Vielleicht ein Traum” under the name of James Joyce in the prestigious Frankfurter Zeitung. In a curious coincidence of names, the publication was in fact the translation by one Irene Kafka “from the English manuscript” of a story entitled “Perchance to Dream” by a writer named Michael Joyce. From what can be gathered of the facts of this affair, it appears that Kafka, subject to her own lapse, mistakenly wrote “James” for “Michael” and the editors of the Frankfurter Zeitung thought they were publishing the translation of a minor work by the famous Irish writer. In any case, alerted to this publication by his German publisher, Joyce’s reaction was nothing less than hysterical. He embarked on a campaign to identify Irene Kafka and Michael Joyce, to denounce the Frankfurter Zeitung and to seek (unsuccessfully) damages of $5,000 (equivalent to the purchasing power of at least $70,400 in 2010 ...). With the help of Sylvia Beach, Joyce’s Paris publisher, this essentially banal affair took on the proportions of an international literary scandal―this despite apologies from the newspaper, the author of the original story and the translator. Ursula Zeller has shown a list of letters written during the three-month period from July to September 1931, in which more than 20 figures in the literary world took an active role. These include such names as T.S. Eliot, Sean O’Casey, Harold Nicolson, Harriet Shaw Weaver, Adrienne Monnier, Philippe Soupault, Padraic Colum and Ernst Robert Curtius. During this period, Joyce was entirely distracted from his work on the manuscript of Work in Progress (later Finnegans Wake). The Frankfurter Zeitung affair nonetheless made its way into the Wake, with a reference to the “Francofurto Siding” (70.04) a play on the Italian franco furto, meaning “outright theft.” What we can make of this bizarre coincidence of another Joyce with another Kafka is that James Joyce exhibits a kind of paranoia of the signature―a fear of the other’s appropriation of his proper name―that far surpasses any material or moral harm that could have come to him had he let the matter drop in the beginning. He was indeed compelled to do so in the end, but only after drawing the attention of most of the European literary world to the imagined damage to his reputation, and to the existence of an otherwise totally obscure writer named Joyce. To paraphrase what Stephen says of Shakespeare ([Ulysses] 9.999), the notes of persecution, banishment and betrayal sound continually in the language of Joyce. Similarly, the idea of the artist as assigned to the sewer of an otherwise clean-smelling world of letters ranges throughout Joyce’s work, from the early satirical verses all the way through Finnegans Wake, where, for example, Shem the Penman, a Joycean alter ego on trial for indecent exposure, is addressed in court as “you and your gift of your gaft of your garbage” (93.19–20). In a later episode Shem’s house is described in indignant tones as the house of O’Shame, “known as the haunted inkbottle” (182.30–31), a dwelling that exceeds everything “even in our western playboyish world for pure mousefarm filth” (183.04) ―Spurr 182–183

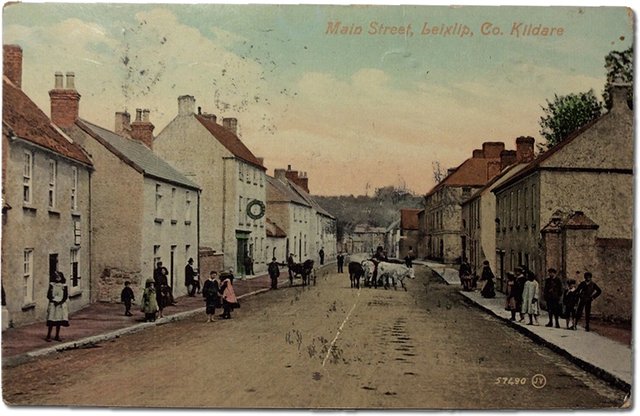

Leixlip

Although Finnegans Wake is unambiguously set in the Mullingar House in Chapelizod, Joyce often conflates this village with two nearby villages further upstream: Lucan and Leixlip. I have elsewhere suggested that Lucan (on the right bank of the Liffey) and Chapelizod (on the left bank) might represent HCE’s rival sons Shaun & Shem, with Lucalizod representing the Oedipal Figure who embodies both brothers. But what about Leixlip? Does this village, which is higher upstream than the other two, represent HCE himself?

The name is of Old Norse origin, meaning salmon leap, which refers to a weir on the Liffey which salmon must leap over on their journey upstream to spawn. HCE’s daughter Issy was born on 29 February, making her the Wake’s leap-year girl. Does this draw her into the Leixlip mix?

HCE is often identified with the Salmon of Knowledge of Irish mythology, and with Finn MacCool, who tasted the salmon and received all its wisdom. Phonetic resemblances tie this Salmon to the Biblical wise man Solomon. These and other fishy connections were explored by Marion Cumpiano in an essay that appeared in the James Joyce Quarterly in 1977:

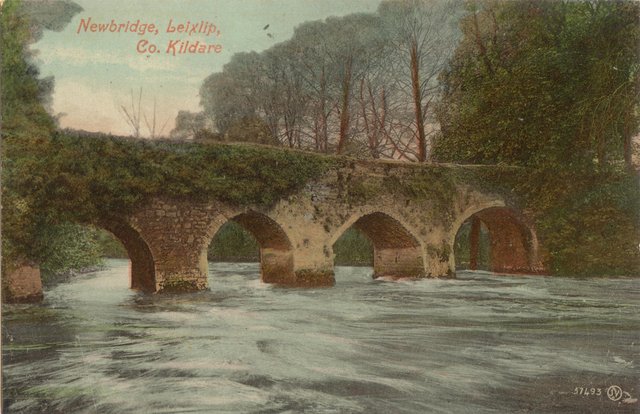

The New Bridge, which crosses the Liffey a few kilometres upstream from Leixlip, was mentioned earlier in this chapter (RFW 050.40). Originally comprising four arches, it was recently rebuilt with three to facilitate the development of the adjacent water reservoir and the Leixlip hydro-electric dam 2 km downstream, which was constructed in 1945. The development of the hydro-electric plant destroyed the historic salmon leap.

I like the idea that Leixlip, being closer to the source of the Liffey than either Lucan or Chapelizod, stands for HCE, the progenitor of Shaun & Shem.

Loose Ends

And finally, let’s wrap up some loose ends:

lets wee brag of praties The Wee Bag of Praties, an Irish folk tune in Charles Stanford’s Complete Collection of Irish Music as Noted by George Petrie. The title means small bag of potatoes.

northroomer Presumably this simply means that Herr Betreffender occupied a room on the north side of HCE’s hotel. North-facing rooms in the Mullingar House overlook the Phoenix Park, where HCE encountered the Cad. John Gordon comments:

69.32-6: “northrooomer ... 32 ... Kommerzial:” Shem-type and Shaun-type, as usual accompanied by numbers 3 and 2. (Will be followed by an 11 at 70.1.) ―John Gordon

the Sockeye Sammon were stopping at the time Irish salmon (grilse) return to Irish rivers to spawn throughout the summer, and spawn from autumn through spring. The sockeye salmon, however, is found in the North Pacific Ocean. The Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) is native to Ireland. O, by the by, there was a James Sammon, family grocer and wine merchant of 167 King Street, Dublin (Glasheen 254).

orange fasting ? Smoked salmon is orange, but cooked salmon is pink. Are the Sockeye Sammons eating nothing but oranges? In the late 18th and early 19th centuries Leixlip was the site of a popular health spa. Or are they Orangemen (Ulster Protestants)? Note the reference below to Holy Romans (Catholics).

to make a heart of glass to take heart to grass, a 17th-century corruption of to take heart of grace, meaning to take courage, to be courageous, to recover one’s courage, to take heart. Note the L/R Interchange, which is reversed below when laugh becomes raugh.

the game of gaze and bandstand butchery was merely a Patsy O’Strap Gazebos often double as public bandstands. There is one such structure in the Phoenix Park, and another in St Stephen’s Green. The Butchers’ March and Paddy O’Snap are two more tunes in Stanford’s Complete Collection of Irish Music. Butcher’s Wood in the Phoenix Park was the scene of the attack on Doctor Sturk in Sheridan Le Fanu’s novel The House by the Churchyard, a key text for Finnegans Wake. It was also the scene of the encounter between Joyce’s father and a tramp―the original seed from which HCE’s Encounter in the Park grew.

roebucks raugh at pinnacle’s peak The deer in the Phoenix Park are fallow deer, not roe deer. Joyce chooses Roebuck because there is a townland in Dublin of that name, and the word echoes Rubek, the hero of Henrik Ibsen’s last play, When We Dead Awaken, who dies on a mountain. In the next chapter, the attack on HCE will be rehearsed once more, but this time on a mountain. Of course, Lots of fun at Finnegan’s Wake is also in there.

Joycean Errata

Most of the 9000-odd emendations made to the text of Finnegans Wake by the editors of The Restored Finnegans Wake, are relatively minor. The majority consist of changes in orthography and punctuation which many readers would not even notice. But here and there Danis Rose & John O’Hanlon have corrected more significant mistakes that crept into the text over the course of the sixteen or seventeen it took Joyce to write the novel. The most egregious of these involve the omission of complete lines―usually due to eyeskip by a typesetter when the book was being prepared for final printing.

One such errant line has been restored to the present paragraph:

a Kommerzial (Gorbotipacco, he was wreaking like Zentral Oylrubber) from Osterich, the U.S.E., paying (Gaul save the mark!) 11/- in the week (Gosh, these wholly romads!) and he missed a soft felt and, take this in, six quid fifteen of conscience money in the first deal of Yuly ...

When this passage was first published in transition in 1927, it read:

a Kommerzial (Gorbotipacco, he was wreaking like Zentral Oylrubber) from Osterich, the U.S.E., paying (Gaul save the mark!) 11/- in the week (Gosh, these wholly romads!) of conscience money in the first deal of Yuly ...

The line and he missed a soft felt and, take this in, six quid fifteen was overlooked by one of the typesetters for transition. Apparently, the line disappeared at draft Level 6, the first set of galleys for transition, in 1927:

At FW 70.02, the first transition galley proof, Level 6, lacks a full typed line from the typescript which was its model, Level 5, “and he missed a soft felt and, take this in, six quid fifteen”, and the loss is never repaired. Because it is such a common type of error, to skip from the end of one line to the beginning of the next line but one, I believe this is a transmissional departure rather than intentional change at what there is much evidence to believe was a now missing Level 5+* which was the typesetter's actual model. ―Cadbury, Lost and Found

Rose & O’Hanlon have also restored the paragraph break after and after this sort. In the published version this paragraph ran on continuously all the way to Adyoe! (RFW 059.39).

And that’s as good a place as any to beach the bark of our tale.

References

- Bill Cadbury et al, Genetic Joyce Studies, Centre for Manuscript Genetics, University of Antwerp, Antwerp (1999 ff)

- Joseph Campbell, Henry Morton Robinson, A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York (1944)

- Marion W Cumpiano, The Salmon and Its Leaps in “Finnegans Wake”, James Joyce Quarterly, Volume 14, Number 3, Pages 255–273, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (1977)

- Adaline Glasheen, Third Census of Finnegans Wake, University of California Press, Berkeley, California (1977)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1963)

- James Hogg, The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green, London (1824)

- Eugene Jolas & Elliot Paul (editors), transition, Number 3, Shakespeare & Co, Paris (1927)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- James Joyce, James Joyce: The Complete Works, Pynch (editor), Online (2013)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

- David Spurr, Paranoid Modernism in Joyce and Kafka, Journal of Modern Literature, Volume 34, Number 2, Pages 178–191, Indian Universiny Press, Bloomington, Indiana (2011)

- Charles Stanford, Complete Collection of Irish Music as Noted by George Petrie, Parts I,–III, Irish Literary Society of London, Boosey & Co, London (1902–1905)

Image Credits

- The Salmon Leap, Leixlip: Francis Wheatley (artist), Yale Center for British Art, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, Public Domain

- The Salmon Leap Inn: © Salmon leap Inn, Fair Use

- Convent of Mercy Schools (Society Street, Ballinasloe): Robert French (photographer), The Lawrence Photograph Collection, National Library of Ireland, Public Domain

- The Brocken: Pascha Johann Friedrich Weitsch (artist), Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, Public Domain

- [Universitätsstrasse 38, Zurich: Joyce’s Home in 1918](Universitätsstrasse 38, Zurich: Joyce’s Home in 1918): Baugeschichtliches Archiv der Stadt Zürich, Creative Commons License

- Frankfurter Zeitung: Front Page of the Anniversary Edition, 26 August 1906, Public Domain

- David Spurr: Copyright Unxnown, Fair Use

- Leixlip (1910): Postcard, Valentine & Sons, Dundee, Public Domain

- Remains of the Leixlip Spa: © Ciaran Reilly (photographer), Fair Use

- Newbridge, Leixlip: Postcard, Valentine & Sons, South Dublin Libraries, Local Studies Collection, County Library, Town Centre, Tallaght, Public Domain

- Fallow Deer in the Phoenix Park: © I Love Mother Earth (photographer), Creative Commons License

Useful Resources

- FWEET

- Jorn Barger: Robotwisdom

- Joyce Tools

- The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

- FinnegansWiki

- James Joyce Digital Archive

- From Swerve of Shore to Bend of Bay

- John Gordon’s Finnegans Wake Blog

- James Joyce: Online Notes