To Proceed

The last ten pages of Chapter 3 of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake comprise an episode known as The Battery at the Gate―a retelling of HCE’s Crime in the Park, Original Sin, and Oedipal Encounter with the Cad. This short paragraph, which follows the description of HCE’s coffin, concludes the first of the three subsections into which the Battery may be divided: Diversified Outrages (RFW 049.30–054.15). As Bill Cadbury explains in How Joyce Wrote Finnegans Wake, Joyce drafted Diversified Outrages after the second subsection, Camelback Excesses, as an alternative to the latter, but in the end he decided to use both (Slote & Crispi 71–76).

First-Draft Version

The first draft of Diversified Outrages comprised one long continuous paragraph. The present paragraph began life as the last half-dozen lines or so:

The conscientious guard in the other case swore that Laddy Cumine, the butcher in the blouse, after having delivered some carcasses went & kicked at the door and when challenged on his oath by the imputed, said simply:

― I am on my oath, you did, as I stressed before.

― You are deeply mistaken, sir, let me tell you, denied McPartland. ―Hayman 73

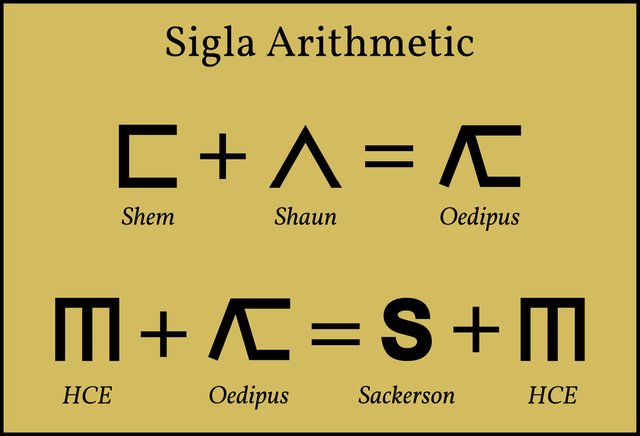

The final version, which runs to eighteen lines in The Restored Finnegans Wake―twenty in the first edition―is only vaguely reminiscent of this brief courtroom exchange. In the earlier draft a guard―ie an Irish policeman, or member of An Gárda Síochána―gives evidence against Laddy Cumine. But in the final version Long Lally Tobkids is a special (ie a special constable) who swears like a Norwegian tailor while giving evidence against a queer sort of a man. In Finnegans Wake, HCE’s curate and manservant Sackerson (S) is often depicted as a constable or policeman, and on his first appearance he is described as both Comestipple and a quhare soort of a mahan (RFW 013.04–06). The Norwegian Captain is HCE, but Kersse the Tailor is the Oedipal Figure.

Adaline Glasheen is also unsure who is involved―her uncertainty is flagged by the leading asterisk:

- Lally or Long Lally Tobkids (or Tomkins ... )―is associated with the Four, save on p. 67 [RFW 053–054] where he is a policeman (see Sacksoun) and is both male and female. Lally references in Scribbledehobble [Connolly 16, 56, 82] suggest a male and a priest, but 67.12–13 [RFW 054.02–03] suggests a dissenting preacher. The use of the ablaut [a change of vowel] ... suggests he-she is not distinct from Lily, who as Susanna is associated with the Four Elders. There is probably a simple solution to this “... contradicting all about Lally” [RFW 302.27]. ―Glasheen 158

Meanwhile, McPartland has become MackPartland (the meatmam’s family, and the oldest in the world except nick, name). Earlier, the Cad was described as Meathman or Meccan? (RFW 041.35). Does this mean that MackPartland is the Cad? But FWEET gives the following gloss:

- Irish: Mac Parthaláin, son of Bartholomew.

HCE is called Bartholomew Porter in III.4 (RFW 436.18). So, is MackPartland one of his sons? In Irish mythology Partholón was the first invader of Ireland after the Flood. His name was derived from the Latin Bartholomaeus, which was thought to mean son of he who stays the waters (Isidore of Seville, Etymologies 7:9).

This confusing blend of characters is one of the most frustrating things about Finnegans Wake. S seems to be giving evidence against himself and against the sons of HCE. But the stuttering in the final version is a sign of HCE’s guilt, so HCE is also giving evidence against himself.

Cumine is a genuine surname of Breton origin―other sources trace it to Irish Gaelic or Scottish Gaelic. In Ireland it took the form Comyn. In the 12th century John Comyn succeeded Dublin’s Patron Saint Laurence O’Toole as Archbishop of Dublin. Is Laddy Cumine a conflation of Larry O’Toole and John Comyn? The interchange of the letters L and R is common throughout Finnegans Wake (O’Hehir 392–393). Later in Finnegans Wake Shem & Shaun will be represented by Laurence O’Toole and his contemporary Thomas à Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

In the final version we also have the names Phillyps Captain and Phelps, which Glasheen glosses thus:

- Phelps (or Phillips), Captain―his opponent is Tomkins. Thus may be included two Dublin actors, Phelps and Tom King; but the Philip and Tom are larger themes. See Lally. ―Glasheen 232

Thomas King and Samuel Phelps were English actors who appeared on the stage in Dublin. Joseph Campbell & Henry Morton Robinson interpret Phillyps as fill lips, implying that the accused had been completely drunk (Campbell & Robinson 75). This is supported by his hiccup (hickicked), as John Gordon notes 67.19.

Continuity with the previous paragraph―a description of HCE’s coffin―is provided by the allusions to the delivery of meat and carcasses by the butcher. Eastman’s Limited was a firm of victuallers (ie butchers) on South Great George’s Street. Note, however, the echo of the Mutt & Jute Episode, which is glossed by Campbell & Robinson:

After delivering some _mutt_on chops and meat jutes on behalf of Messrs. Otto Sands and Eastman, Limerick, Victualers ... ―Campbell & Robinson 75

In a footnote they add:

The Mutt and Jute episode was a greatly distorted dream variant of the archetypal Park encounter between HCE (Jute) and the Native Antagonist (Mutt). This antagonist is, variously, the Cad, the masked assailant, the policeman, and the ballad gentry. ―Campbell & Robinson 75 fn *

Remember that HCE’s fall is precipitated by the Oedipal Invader, who then becomes the new HCE, while the old HCE becomes his servant. Thus Mutt began as HCE but ended up as S, while Jute began as the Oedipal Figure but ended up as HCE. This is why they swop hats (RFW 013.11). To further complicate matters, the Oedipal Figure embodies both of HCE’s sons, who are referenced―as Cain & Abel―by the Biblical quote in the last line of this paragraph:

And Cain was very wroth, and his countenance fell. (Genesis 4:5)

And Glasheen’s detection of the Four Old Men in this passage seems to be confirmed by Messrs Otto Sands and Eastman, Limericked, which conceals the four cardinal points of North, South, East and West (Limerick is in the west of Ireland). The Four, who embody space, are associated with these directions. They are also the judges at HCE’s trial.

Chemistry in Finnegans Wake

One curious addition Joyce made to this paragraph when he revised it was the following piece of chemistry:

- We might leave that nitrience of oxagiants to take its free of the air and just analectralyse that very chymirical combination, the gasbag where the warder works. And try to pour somour heiteroscene up the almostfere. In the bottled heliose case ... [RFW 053.37–40]

Joyce was never particularly interested in science, but he wrote Finnegans Wake against the backdrop of one of the most remarkable revolutions in the history of physics. Einstein’s groundbreaking theories of relativity were still in their infancy, and thinkers like Schrödinger, Heisenberg and Dirac were only beginning to uncover the secrets of the quantum world. In 1932, when Joyce was working on Book II of Finnegans Wake, an Irishman, Ernest Walton―in collaboration with his English colleague John Cockcroft―became the first person to artificially split the atom, confirming Einstein’s E=mc2.

An avant-garde work like Finnegans Wake could hardly ignore these developments. Joyce’s ambivalent attitude to science could be no bar. And that his attitude was ambivalent is clear from the following, which his brother Stanislaus wrote in his diary on 13 August 1904:

It will be obvious that whatever method there is in Jim’s life is highly unscientific, yet in theory he approves only of the scientific method. About science he knows ‛damn all’, and if he has the same blood in him as I have he should dislike it. I call it a lack of vigilant reticence in him that he is ever-ready to admit the legitimacy of the scientist’s raids outside his frontiers. The word ‛scientific’ is always a word of praise in his mouth ... Jim boasts―for he often boasts now―of being modern. ―Healey 53–34

In 1996 the linguist Harry Burrell wrote the definitive article on the subject of Chemistry and Physics in Finnegans Wake. Noting the decided lack of scientific texts in Joyce’s libraries, he surmised that the principal sources for the scientific elements in Finnegans Wake were The Encyclopædia Britannica and Joyce’s own memories of things he had learnt at school or in college. According to FWEET, however, the present passage draws on Henry Roscoe’s 1872 textbook Chemistry, which Joyce used about fifty times in the course of Finnegans Wake. This is supported by a number of notes he made in two of the Finnegans Wake notebooks, VI.B.45 and VI.B.15 (James Joyce Digital Archive).

Burrell’s glosses on the passage quoted above are as follows:

067.07–8 “that nitrience of oxagiants to take its free of the air and just analectralyse” In the nitrogen fixation process of fertilizer manufacturing, air is passed through an electric arc causing the chemical combination of nitrogen and oxygen. Nitrous oxide and nitric oxide are the gases produced which could be kept in a “gasbag.”

067.08–9 “analectrolyse that very chymerical combination” This includes: analyse the chemical combination. Some analytical procedures involve electrolysis.

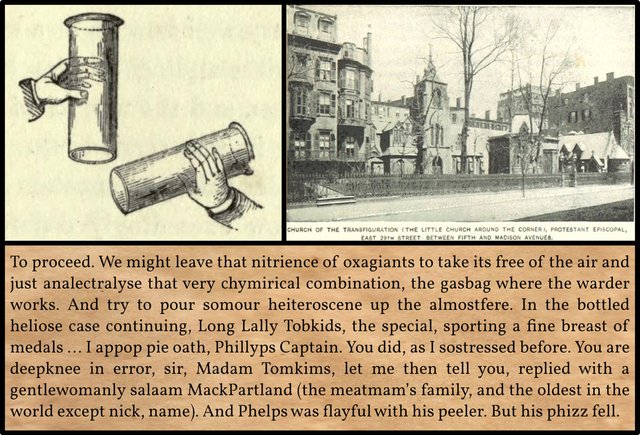

067.09–10 “pour somour heiterscene up thealmostfere” This sounds like: pour some more hydrogen up the atmosphere. Hydrogen, being lighter than air, has to be poured upward from one container to another, the receiving container being held up side down. Also hydrogen is lost from the earth’s atmosphere because the earth’s gravity can not retain it.

067.10 “bottled heliose” Helium is sold in steel bottles. ―Burrell 198–199

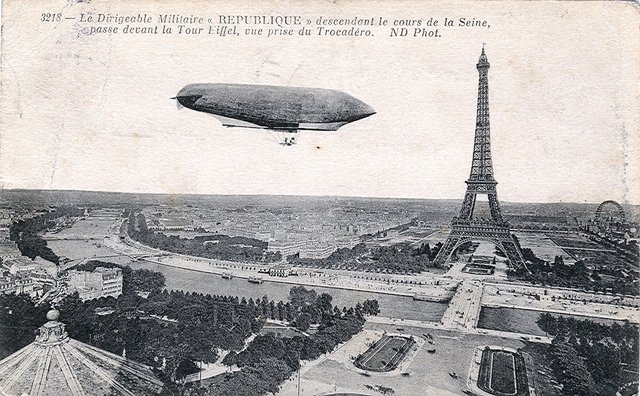

I assume Joyce added these elements because the case against HCE is just a lot of hot air. As John Gordon notes, the gasbag may also be a blimp.

67.9: “gasbag:” blimp or dirigible, taking its “free of the air” (67.8). Given that they were lifted by hydrogen or helium, and that the latter shows up at 67.10 as “heliose,” I agree with C. George Sandeluscu in hearing “heiterscene,” on the next line, as echoing “hydrogen.” ―Gordon 67.9

And that’s as good a place as any to beach the bark of our tale.

References

- Harry Burrell, Chemistry and Physics in Finnegans Wake, Thomas F Staley (editor), Joyce Studies Annual, Volume 7, Pages 192–218, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1996)

- Joseph Campbell, Henry Morton Robinson, A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York (1944)

- Thomas Edmund Connolly (editor), James Joyce’s Scribbledehobble: The Ur-Workbook for Finnegans Wake, Edited with Notes and an Introduction, Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Illinois (1961)

- Michael Faraday, A Course of Six Lectures on the Various Forces of Matter, and Their Relations to Each Other, Richard Griffin and Company, London (1860)

- Adaline Glasheen, Third Census of Finnegans Wake, University of California Press, Berkeley, California (1977)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1963)

- George H Healey, The Complete Dublin Diary of Stanislaus Joyce, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York (1971)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- James Joyce, James Joyce: The Complete Works, Pynch (editor), Online (2013)

- Brendan O’Hehir, A Gaelic Lexicon for Finnegans Wake, and Glossary for Joyce’s Other Works, University of California Press, Berkeley, California (1967)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

- Henry Roscoe, Chemistry, Macmillan and Co, London (1872)

- John Warburton, James Whitelaw, Robert Walsh, A History of the City of Dublin, Volume 1, Volume 2, T Cadell & W Davies, London (1818)

Image Credits

- Pouring Hydrogen Up: Michael Faraday, Six Lectures, Figure 28, Public Domain

- The Little Church Around the Corner: Moses King, King’s Handbook of New York City, Page 357, Boston, Massachusetts (1893), Public Domain

- Adaline Glasheen: Alexander Brook (artist), © The Estate of Alexander Brook, Fair Use

- Cyril Connolly: Howard Coster (photographer), © National Portrait Gallery, London, Fair Use

- Tom King: William Daniell (artist), National Portrait Gallery, London, Public Domain

- Samuel Phelps: Nicholas Joseph Crowley (artist), The Box, Plymouth, Public Domain

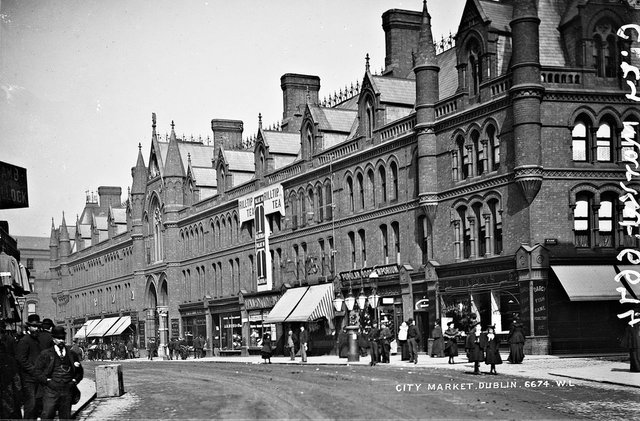

- South Great George’s Street: Robert French (photographer), Lawrence Photograph Collection, National Library of Ireland, Public Domain

- Stanislaus Joyce: Anonymous Photograph, Public Domain

- Henry Roscoe: Walery [Stanisław Julian Ostroróg] (photographer), Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

- The Military Airship La République over Paris (1908–09): Neurdein (photographers), French Postcard from 1913, Wolfgang Sauber (collector), Public Domain

Useful Resources

- FWEET

- Jorn Barger: Robotwisdom

- Joyce Tools

- The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

- FinnegansWiki

- James Joyce Digital Archive

- John Gordon’s Finnegans Wake Blog