Gandhi's flawed fast - 99 hours in Rajkot

Mohandas K. Gandhi, who described fasting as a weapon that “cannot be lightly wielded,” used it over the last three decades of his life for personal, social, and political change. His nonviolent blade was strengthened by the thought and deliberation that went into its use, but on one occasion, he apologized after such a fast. Gandhi discovered that his fast in Rajkot had been influenced by the element of coercion. What was it that led him down the path to a flawed fast in 1939?

At the beginning of the decade, Gandhi's Salt March and the corresponding civil disobedience campaign had attracted world attention to this British colony fighting for liberty. In response, the British passed the 1935 Government of India Act, a legislative framework that ostensibly set the stage for a transition to independence. It wooed the princely states with oversized power, but most rulers looked for ways to preserve their own fiefdoms instead.

Calls for democratic reform in these princely states spread across India, thanks in part to Gandhi's inclusion of women in his civil disobedience campaigns. In December 1938, these efforts produced an agreement in Rajkot. The Thakore Saheb agreed to appoint a reforms commission to draft a state constitution, then reneged. A civil disobedience movement sprang up, with Vallabhbhai Patel and his daughter Manibehn as prominent figures. The pair were dedicated followers of Gandhi, and Patel would later serve as India's first Deputy Prime Minister.

As news of the struggle in Rajkot spread, Gandhi decided to visit and see the situation firsthand. Manibehn and many others had been in jail for weeks. Hunger strikes were breaking out as prisoners complained of endemic abuse. Gandhi visited prisoners in several jails, and “was very much moved by the statements made.” When no progress was made after several meetings with the ruler's advisor, Gandhi sent a letter to the Thakore Saheb (and Bcc'd the British Viceroy). In his letter, Gandhi reminded the Thakore Saheb of their common roots, which prompted his duty to begin a fast, with the hope of spurring his conscience into embracing reform.

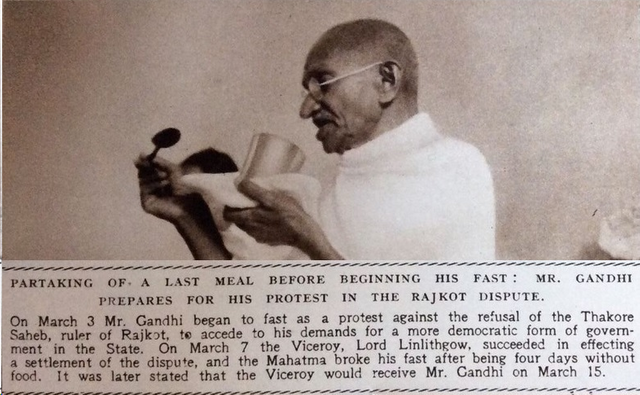

The conditions Gandhi laid out were basic. He demanded appointments to establish a reforms committee, that resources for the committee be made available, and that all satyagraha prisoners be released. Word of the fast leaked, and reporters gathered around him on the morning of March 3, 1939. When no response came from the Thakore Saheb by noon, Gandhi began his fast to the death, proclaiming, “I have no recollection of a single experiment of mine in fasting having been a fruitless effort.”

Gandhi was 69 years old, and this was his first extended fast in almost five years. Friends and associates were concerned for his health, and surprised by what appeared to be a hasty decision. Gandhi, on the other hand, was satisfied that he was doing the right thing, and “slept peacefully” for the first time “since his arrival in Rajkot.” He was confident the Thakore Saheb would accept this as a face-saving solution.

The fast stretched into a third day. Gandhi stayed in bed to conserve energy, and found spiritual nourishment by listening to a daily recital of the 18 chapters of the Bhagavad Gita. While waiting for the Thakore Saheb to meet his demands, he reached out to Lord Linlithgow, the British Viceroy, and asked for help in convincing the prince to uphold the December agreement.

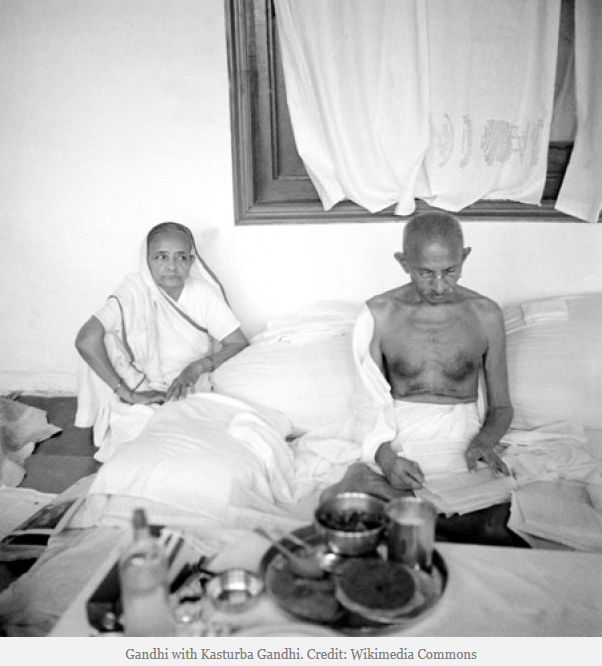

On the morning of March 7, the fifth day of the fast, Gandhi received a favorable response. The British, well aware of the influence Gandhi's life had on the tranquility of the nation, suggested arbitration by the Chief Justice of India. The Viceroy also promised his personal influence to make sure the Thakore Saheb followed through. This was acceptable, and 99 hours since his last meal, Gandhi broke his fast in the presence of his wife Kasturba. After the brief ceremony, arrangements were made to immediately release the satyagaha prisoners, and Gandhi held a press conference from his bed, crediting the Viceroy for brokering a settlement.

However, the dispute was still unresolved a month later. The Chief Justice had awarded a judgment in favor of Patel, but the Thakore Saheb still refused to make the required committee appointments. A frustrated Gandhi again reached out to the British, complaining of frivolous delays and reminding them that the fast was “only suspended.” Nonetheless, the reforms committee remained ethereal, lacking the necessary political will to coalesce.

Finally, Gandhi admitted defeat, and on May 17, he apologized for his fast and renounced the award of the Chief Justice.

On further reflection, Gandhi realized what he had done wrong. “To be pure,” his fast should have focused only on melting the heart of the Thakore Saheb. Instead, Gandhi had used the Viceroy's influence to pressure the prince into submission. His fast had been flawed, tinted with “the way of himsa, or coercion.” He apologized to the Thakore Saheb, the Viceroy, the Chief Justice, the Muslims, the Bhayats, and others involved in the dispute, but not Vallabhbhai Patel or the satyagraha prisoners who had been released.

Why had Gandhi launched into a coercive fast to the death? What did he accomplish with his 99 hour flawed fast? The answer may be found in another question: Who had he seen while meeting the Thakore Saheb's political prisoners?

One of the "state guests" was Kasturba.

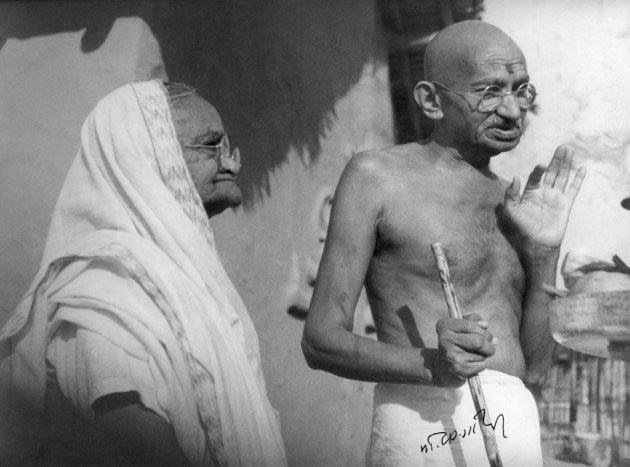

Kasturba Gandhi was just a few months shy of her seventieth birthday, but when she'd heard of Manibehn Patel's arrest, she sprang into action. She said goodbye to a reluctant husband, and set off for Rajkot with Mridula Sarabhai as a traveling companion. Kasturba had grown up in Rajkot and started her family there, and was determined to help rally the women of that city. Unfortunately, the pair was arrested after arriving February 3rd.

Her political prestige kept her out of Sardhard prison. Instead, she was sequestered at summer cottage in the village of Tramba, a place with a scandalous reputation among the city's women. Kasturba's grandson Arun describes the reason so many Rajkot women were engaging in civil disobedience; “It was the prince's habit,” he writes, “to kidnap beautiful young girls [and] take them to his royal 'fun house.'”

In mid-February, Gandhi learned that Kasturba was being held in solitary confinement. He reassured her in his frequent letters, but could do nothing else across the miles. It was Manibehn Patel, also detained at Tramba, who rescued her by starting a hunger strike. Kasturba was returned to her friends, and Arun Gandhi writes that his grandmother “never wavered, never complained.”

Jail-going had been a family occupation for 30 years, and a regular routine developed - letters always flowed from Gandhi, including long, gossipy letters to her in Yerwada Jail for the first half of 1934. But when Gandhi saw the imprisoned Kasturba on the evening of February 28, it may have been the first time he ever physically visited her.

They ate a dinner of simple prison food and talked. The details of the marital conversation are long lost, but it's reasonable to speculate that they reminisced about their shared history in Rajkot. It was where they'd first lived as husband and wife, young Mohandas Gandhi himself just 12 years old. Their room in the family house was adequate, but too small when the teenage couple fought. Kasturba had given birth twice before Gandhi had left for law school in London at the age of 18. There had been countless miles traveled as their their four sons grew up between India and South Africa, and there had been many jail cells where she had visited Gandhi. After all these years of following him, Mohandas had come to Kasturba.

As they ate dinner, Gandhi must have appraised his wife's health. Her decades were showing; the month before she'd fainted in the bathroom, and might have died if their youngest son hadn't acted quickly. Despite the risks, she'd been determined to strike out for Rajkot, and he acquiesced. It helped that her traveling companion, Mridula Sarabhai, was the daughter of an old family friend. Kasturba had followed him across the continents, across the decades, but in this struggle, in Rajkot, she was blazing a path for him to follow.

How could he help her now?

Fasting was Gandhi's most powerful weapon, and he asserted he was “an artist in this subject.” Biographer Erik Erikson describes the reaction of his countrymen to these periodic events; “All of India would hold its breath while the Mahatma fasted, and whole cities would leave their lamps unlit in the evening in order to be near him in the dark.”

Under the eyes of the press, Gandhi started his fast to the death on March 3, 1939. Ninety-nine hours later, his wife - Gandhi later described her to the Viceroy as his "better half" - was free and by his side as he sipped a glass of juice. Those around him celebrated the settlement and release of prisoners by his nonviolent weapon, but Gandhi wasn't satisfied. He discovered that his fast was imperfect and apologized for it.

It was for this type of honesty and humility that millions called him Mahatma, or 'great soul'.

TL;DR - If the motive for Gandhi's fast wasn't up to his personal high standards, maybe we should still see if for the success that it was: Man rescues the woman he loves from unjust authority, and he does it nonviolently. (This is also my pitch for Taken 5: The Fasting Furious.)

You're invited to join the next fast for peace, a 24-hour, water only fast on the 15th of every month. Fastforpeace.org promotes Gandhi's lessons of truth and nonviolence, tolerance and voluntary temperance, simplicity and self-control with a monthly fast for peace. Peace starts with us being the change we want to see in our communities, our country, and the world. #fastforpeace

Sources:

Photos from Wikimedia Commons.

Gandhi's Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence (Erikson, 1969)

Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World (Guha, 2018)

Gandhi before India (Guha, 2013)

Gandhi: The Man, The Empire, and his People (Rajmohan Gandhi, 2006)

Kasturba: A Life (Arun Gandhi, 2000)

The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi

The Rajkot Fast (Pyarelal, 1939)

If your health permits, you're also invited to commemorate Gandhi's fast for love on March 3-7 each year. No food for 99 hours, water only for extra difficulty. #99hourlovefast