Most Significant Figures in History #6: George Washington

Main Facts

February 22, 1732 (February 11, 1731 – December 14, 1799) was an American politician and soldier who served as the first President of the United States from 1789 to 1797 and was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He served as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and later presided over the 1787 convention that drafted the United States Constitution. He is popularly considered the driving force behind the nation's establishment and came to be known as the "father of the country," both during his lifetime and to this day.

.jpg)

Early Life

George Washington was the first child of Augustine Washington (1694–1743) and his second wife Mary Ball Washington (1708–1789), born on their Pope's Creek Estate near present-day Colonial Beach in Westmoreland County, Virginia. He was born on February 11, 1731, according to the Julian calendar and Annunciation Style of enumerating years then in use in the British Empire. The Gregorian calendar was adopted within the British Empire in 1752, and it renders a birth date of February 22, 1732.

Washington was of primarily English gentry descent, especially from Sulgrave, England. His great-grandfather John Washington emigrated to Virginia in 1656 and began accumulating land and slaves, as did his son Lawrence and his grandson, George's father Augustine. Augustine was a tobacco planter who also tried his hand in iron-manufacturing ventures. In George's youth, the Washingtons were moderately prosperous members of the Virginia gentry, of "middling rank" rather than one of the leading planter families

by Howard Chandler Christy, 1940

Constitutional Convention

Washington's retirement to personal business at Mount Vernon was short-lived. He made an exploratory trip to the western frontier in 1784 and inspected his land holdings in Western Pennsylvania that had been earned decades earlier for his service in the French and Indian War. There he confronted squatters, including David Reed and the Covenanters; they vacated, but only after losing a court decision heard in Washington, Pennsylvania in 1786. He also facilitated the creation of the Potomac Company, a public–private partnership that sought to link the Potomac River with the Ohio River, but technical and financial challenges rendered the company unprofitable.

After much reluctance, he was persuaded to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787 as a delegate from Virginia, where he was unanimously elected as president of the Convention. He held considerable criticism of the Articles of Confederation of the thirteen colonies, for the weak central government which it established, referring to the Articles as no more than "a rope of sand" to support the new nation. Washington's view for the need of a strong federal government grew out of the recent war, as well as the inability of the Continental Congress to rally the states to provide for the needs of the military, as was clearly demonstrated for him during the winter at Valley Forge. The general populace, however, did not share Washington's views of a strong federal government binding the states together, comparing such a prevailing entity to the British Parliament that previously ruled and taxed the colonies.

Washington's participation in the debates was minor, although he cast his vote when called upon; his prestige facilitated the collegiality and productivity of the delegates. After a couple of months into the task, Washington told Alexander Hamilton, "I almost despair of seeing a favorable issue to the proceedings of our convention and do therefore repent having had any agency in the business." Following the Convention, his support convinced many, but not all of his colleagues, to vote for ratification. He unsuccessfully lobbied anti-federalist Patrick Henry, saying that "the adoption of it under the present circumstances of the Union is in my opinion desirable;" he declared that the only alternative would be anarchy. Nevertheless, he did not consider it appropriate to cast his vote in favor of adoption for Virginia, since he was expected to be nominated president under it. The new Constitution was subsequently ratified by all thirteen states. The delegates to the convention designed the presidency with Washington in mind, allowing him to define the office by establishing precedent once elected. Washington thought that the achievements were monumental once they were finally completed.

Presidency

The Electoral College unanimously elected Washington as the first president in 1789 and again in 1792. He remains the only president to receive the totality of electoral votes. John Adams received the next highest vote total and was elected vice president. Washington was inaugurated on April 30, 1789, taking the first presidential oath of office on the balcony of Federal Hall in New York City. The oath, as follows, was administered by Chancellor Robert R. Livingston: "I do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States and will, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States." Historian John R. Alden indicates that Washington added the words "so help me God."

The 1st United States Congress voted to pay Washington a salary of $25,000 a year—a large sum in 1789, valued at about $340,000 in 2015 dollars. Washington faced financial troubles then, yet he initially declined the salary. At the urging of Congress, he ultimately accepted the payment to avoid setting a precedent whereby the presidency would be perceived as limited only to independently wealthy individuals who could serve without any salary. The president was aware that everything which he did set a precedent, and he attended carefully to the pomp and ceremony of office, making sure that the titles and trappings were suitably republican and never emulated European royal courts. To that end, he preferred the title "Mr. President" to the more majestic names proposed by the Senate.

Washington proved an able administrator and established many precedents in the functions of the presidency, including messages to Congress and the cabinet form of government. He set the standard for tolerance of opposition voices, despite fears that a democratic system would lead to political violence, and conducted a smooth transition of power to his successor. He was an excellent delegator and judge of talent and character; he talked regularly with department heads and listened to their advice before making a final decision. In handling routine tasks, he was "systematic, orderly, energetic, solicitous of the opinion of others ... but decisive, intent upon general goals and the consistency of particular actions with them." After reluctantly serving a second term, Washington refused to run for a third, establishing the tradition of a maximum of two terms for a president, which was solidified by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

.jpg)

Retirement

Washington retired from the presidency in March 1797 and returned to Mount Vernon with a profound sense of relief. He devoted much time to his plantations and other business interests, including his distillery, which produced its first batch of spirits in February 1797. Chernow 2010 explains that his plantation operations were only minimally profitable. The lands out west yielded little income because they were under attack by Indians, and the squatters living there refused to pay him rent. Washington attempted to sell off these holdings but failed to obtain the price that he desired. Meanwhile, he was losing money at Mount Vernon due to a glut of unproductive slaves, which he declined to sell due to a desire to keep families intact, and due to questions as to whether the slaves rightfully belonged to him or to Martha.

Most Americans assumed that he was rich because of the well-known "glorified façade of wealth and grandeur" at Mount Vernon, nearly all his wealth was tied up in land or slaves. Historians estimate that his estate was worth about $1 million in 1799 dollars, equivalent to about $19.9 million in 2014 purchasing power.

By 1798, relations with France had deteriorated to the point that war seemed imminent. President Adams offered Washington a commission as lieutenant general on July 4, 1798, and as Commander-in-chief of the armies raised or to be raised for service in a prospective war. He accepted and served as the senior officer of the United States Army from July 13, 1798, until his death seventeen months later. He participated in the planning for a Provisional Army to meet any emergency that might arise but avoided involvement in details as much as possible. He delegated most of the work, including active leadership of the army, to Hamilton, who was then serving as a major general in the U.S. Army. No French army invaded the United States during this period, and Washington did not assume a field command.

Death

On Thursday, December 12, 1799, Washington spent several hours inspecting his plantation on horseback, in snow, hail, and freezing rain; that evening, he ate his supper without changing from his wet clothes. He awoke the next morning with a severe sore throat and became increasingly hoarse as the day progressed, yet still rode out in the heavy snow, marking trees that he wanted cut on the estate. Some time around 3 a.m. that Saturday, he suddenly awoke with severe difficulty breathing and almost completely unable to speak or swallow. He was a firm believer in bloodletting, which was a standard medical practice of that era which he had used to treat various ailments of slaves on his plantation. He ordered estate overseer Albin Rawlins to remove half a pint of his blood.

Three physicians were summoned, including Washington's personal physician Dr. James Craik, along with Dr. Gustavus Brown and Dr. Elisha Dick. Craik and Brown thought that Washington had "quinsey" or "quincy", while Dick thought that the condition was more serious or a "violent inflammation of the throat". By the time that the three physicians finished their treatments and bloodletting of the president, there had been a massive volume of blood loss—half or more of his total blood content was removed over the course of just a few hours. Dr. Dick recognized that the bloodletting and other treatments were failing, and he proposed performing an emergency tracheotomy, a procedure that few American physicians were familiar with at the time, as a last-ditch effort to save Washington's life, but the other two doctors disapproved.

Washington died at home around 10 p.m. on Saturday, December 14, 1799, aged 67. In his journal, Tobias Lear recorded Washington's last words as "'Tis well."

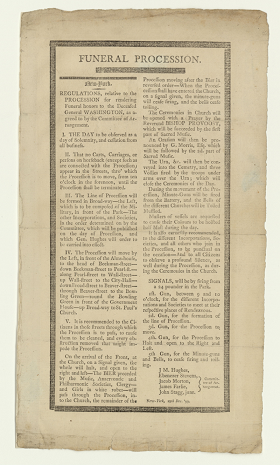

A funeral was held at Mount Vernon on December 18, 1799 where Washington's body was interred. Congress passed a joint resolution to construct a marble monument for his body in the planned crypt below the rotunda of the center section of the Capitol (then still under construction), a plan acquiesced to by Martha. In December 1800, the House passed an appropriations bill for $200,000 to build the mausoleum, which was to be a pyramid with a 100-foot (30 m) square base. Southern representatives and senators opposed the plan and defeated the measure because they felt that it was best to have Washington's body remain at Mount Vernon.

Throughout the world, people admired Washington and were saddened by his death. In the United States, memorial processions were held in major cities and thousands wore mourning clothes for months. Martha Washington wore a black mourning cape for one year. In France, First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte ordered ten days of mourning throughout the country. Ships of the British Royal Navy's Channel Fleet lowered their flags to half mast to honor his passing.

To protect their privacy, Martha Washington burned the correspondence which they had exchanged; only five letters between the couple are known to have survived, two letters from Martha to George and three from him to her.

I hope you liked another article of the "Most Significant Figures in History". Note, that the number in the title does NOT mean that the one figure had more influence than the other.

Thank you for reading, I hope you liked it. If you did, consider upvoting and following me. :)

Nice history

This post has received a 15.06 % upvote from @booster thanks to: @elephantas1.