History of the United States PART 3 EUROPEAN COLONIZATION

European colonization

Main article: Colonial history of the United States

European territorial claims in North America, c. 1750

France

Great Britain

Spain

After a period of exploration sponsored by major European nations, the first successful English settlement was established in 1607. Europeans brought horses, cattle, and hogs to the Americas and, in turn, took back maize, turkeys, tomatoes, potatoes, tobacco, beans, and squash to Europe. Many explorers and early settlers died after being exposed to new diseases in the Americas. However, the effects of new Eurasian diseases carried by the colonists, especially smallpox and measles, were much worse for the Native Americans, as they had no immunity to them. They suffered epidemics and died in very large numbers, usually before large-scale European settlement began. Their societies were disrupted and hollowed out by the scale of deaths.[19][20]

First settlements

Main articles: Spanish colonization of the Americas, Dutch colonization of the Americas, New Sweden, and French colonization of the Americas

Spanish contact

Spanish explorers were the first Europeans to reach the present-day United States, after Christopher Columbus's expeditions (beginning in 1492) established possessions in the Caribbean, including the modern-day U.S. territories of Puerto Rico, and (partly) the U.S. Virgin Islands. Juan Ponce de León landed in Florida in 1513.[21] Spanish expeditions quickly reached the Appalachian Mountains, the Mississippi River, the Grand Canyon,[22] and the Great Plains.[23]

MENU0:00

The Letter of Christopher Columbus on the Discovery of America to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain

In 1539, Hernando de Soto extensively explored the Southeast,[23] and a year later Francisco Coronado explored from Arizona to central Kansas in search of gold.[23] Escaped horses from Coronado's party spread over the Great Plains, and the Plains Indians mastered horsemanship within a few generations.[7] Small Spanish settlements eventually grew to become important cities, such as San Antonio, Albuquerque, Tucson, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.[24]

Dutch Mid-Atlantic

The Dutch West India Company sent explorer Henry Hudson to search for a Northwest Passage to Asia in 1609. New Netherland was established in 1621 by the company to capitalize on the North American fur trade. Growth was slow at first due to mismanagement by the Dutch and Native American conflicts. After the Dutch purchased the island of Manhattan from the Native Americans for a reported price of US$24, the land was named New Amsterdam and became the capital of New Netherland. The town rapidly expanded and in the mid 1600s it became an important trading center and port. Despite being Calvinists and building the Reformed Church in America, the Dutch were tolerant of other religions and cultures and traded with the Iroquois to the north.[25]

The colony served as a barrier to British expansion from New England, and as a result a series of wars were fought. The colony was taken over by Britain in 1664 and its capital was renamed New York City. New Netherland left an enduring legacy on American cultural and political life of religious tolerance and sensible trade in urban areas and rural traditionalism in the countryside (typified by the story of Rip Van Winkle). Notable Americans of Dutch descent include Martin Van Buren, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt and the Frelinghuysens.[25]

Swedish settlement

In the early years of the Swedish Empire, Swedish, Dutch, and German stockholders formed the New Sweden Company to trade furs and tobacco in North America. The company's first expedition was led by Peter Minuit, who had been governor of New Netherland from 1626 to 1631 but left after a dispute with the Dutch government, and landed in Delaware Bay in March 1638. The settlers founded Fort Christina at the site of modern-day Wilmington, Delaware, and made treaties with the indigenous groups for land ownership on both sides of the Delaware River. Over the following seventeen years, 12 more expeditions brought settlers from the Swedish Empire (which also included contemporary Finland, Estonia, and portions of Latvia, Norway, Russia, Poland, and Germany) to New Sweden. The colony established 19 permanent settlements along with many farms, extending into modern-day Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. It was incorporated into New Netherland in 1655 after a Dutch invasion from the neighboring New Netherland colony during the Second Northern War.[26][27]

French and Spanish conflict

Giovanni da Verrazzano landed in North Carolina in 1524, and was the first European to sail into New York Harbor and Narragansett Bay. A decade later, Jacques Cartier sailed in search of the Northwest Passage, but instead discovered the Saint Lawrence River and laid the foundation for French colonization of the Americas in New France. After the collapse of the first Quebec colony in the 1540s, French Huguenots settled at Fort Caroline near present-day Jacksonville in Florida. In 1565, Spanish forces led by Pedro Menéndez destroyed the settlement and established the first European settlement in what would become the United States — St. Augustine.

After this, the French mostly remained in Quebec and Acadia, but far-reaching trade relationships with Native Americans throughout the Great Lakes and Midwest spread their influence. French colonists in small villages along the Mississippi and Illinois rivers lived in farming communities that served as a grain source for Gulf Coast settlements. The French established plantations in Louisiana along with settling New Orleans, Mobile and Biloxi.

British colonies

Further information: British colonization of the Americas

MENU0:00

Excerpt of a Description of New England by English explorer John Smith, published in 1616.

The Mayflower, which transported Pilgrims to the New World. During the first winter at Plymouth, about half of the Pilgrims died.[28]

The English, drawn in by Francis Drake's raids on Spanish treasure ships leaving the New World, settled the strip of land along the east coast in the 1600s. The first British colony in North America was established at Roanoke by Walter Raleigh in 1585, but failed. It would be twenty years before another attempt.[7]

The early British colonies were established by private groups seeking profit, and were marked by starvation, disease, and Native American attacks. Many immigrants were people seeking religious freedom or escaping political oppression, peasants displaced by the Industrial Revolution, or those simply seeking adventure and opportunity.

In some areas, Native Americans taught colonists how to plant and harvest the native crops. In others, they attacked the settlers. Virgin forests provided an ample supply of building material and firewood. Natural inlets and harbors lined the coast, providing easy ports for essential trade with Europe. Settlements remained close to the coast due to this as well as Native American resistance and the Appalachian Mountains that were found in the interior.[7]

First settlement in Jamestown

Squanto known for having been an early liaison between the native populations in Southern New England and the Mayflower settlers, who made their settlement at the site of Squanto's former summer village.

The first successful English colony, Jamestown, was established by the Virginia Company in 1607 on the James River in Virginia. The colonists were preoccupied with the search for gold and were ill-equipped for life in the New World. Captain John Smith held the fledgling Jamestown together in the first year, and the colony descended into anarchy and nearly failed when he returned to England two years later. John Rolfe began experimenting with tobacco from the West Indies in 1612, and by 1614 the first shipment arrived in London. It became Virginia's chief source of revenue within a decade.

In 1624, after years of disease and Indian attacks, including the Powhatan attack of 1622, King James I revoked the Virginia Company's charter and made Virginia a royal colony.

New England

Jennie Augusta Brownscombe, The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth, 1914, Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Massachusetts

New England was initially settled primarily by Puritans fleeing religious persecution. The Pilgrims sailed for Virginia on the Mayflower in 1620, but were knocked off course by a storm and landed at Plymouth, where they agreed to a social contract of rules in the Mayflower Compact. Like Jamestown, Plymouth suffered from disease and starvation, but local Wampanoag Indians taught the colonists how to farm maize.

Plymouth was followed by the Puritans and Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. They maintained a charter for self-government separate from England, and elected founder John Winthrop as the governor for most of its early years. Roger Williams opposed Winthrop's treatment of Native Americans and religious intolerance, and established the colony of Providence Plantations, later Rhode Island, on the basis of freedom of religion. Other colonists established settlements in the Connecticut River Valley, and on the coasts of present-day New Hampshire and Maine. Native American attacks continued, with the most significant occurring in the 1637 Pequot War and the 1675 King Philip's War.

New England became a center of commerce and industry due to the poor, mountainous soil making agriculture difficult. Rivers were harnessed to power grain mills and sawmills, and the numerous harbors facilitated trade. Tight-knit villages developed around these industrial centers, and Boston became one of America's most important ports.

Middle Colonies

Indians trade 90-lb packs of furs at a Hudson's Bay Company trading post in the 19th century.

In the 1660s, the Middle Colonies of New York, New Jersey, and Delaware were established in the former Dutch New Netherland, and were characterized by a large degree of ethnic and religious diversity. At the same time, the Iroquois of New York, strengthened by years of fur trading with Europeans, formed the powerful Iroquois Confederacy.

The last colony in this region was Pennsylvania, established in 1681 by William Penn as a home for religious dissenters, including Quakers, Methodists, and the Amish.[29] The capital of colony, Philadelphia, became a dominant commercial center in a few short years, with busy docks and brick houses. While Quakers populated the city, German immigrants began to flood into the Pennsylvanian hills and forests, while the Scots-Irish pushed into the far western frontier.

Southern Colonies

The extremely rural Southern Colonies contrasted greatly with the north. Outside of Virginia, the first British colony south of New England was Maryland, established as a Catholic haven in 1632. The economy of these two colonies was built entirely on yeoman farmers and planters. The planters established themselves in the Tidewater region of Virginia, establishing massive plantations with slave labor, while the small-scale farmers made their way into political office.

In 1670, the Province of Carolina was established, and Charleston became the region's great trading port. While Virginia's economy was based on tobacco, Carolina was much more diversified, exporting rice, indigo, and lumber as well. In 1712 the colony was split in half, creating North and South Carolina. The Georgia Colony – the last of the Thirteen Colonies – was established by James Oglethorpe in 1732 as a border to Spanish Florida and a reform colony for former prisoners and the poor.[29]

The Indian massacre of Jamestown settlers in 1622. Soon the colonists in the South feared all natives as enemies.

John Gadsby Chapman, Baptism of Pocahontas (1840), on display in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol.

Religion

Religiosity expanded greatly after the First Great Awakening, a religious revival in the 1740s which was led by preachers such as Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield. American Evangelicals affected by the Awakening added a new emphasis on divine outpourings of the Holy Spirit and conversions that implanted new believers with an intense love for God. Revivals encapsulated those hallmarks and carried the newly created evangelicalism into the early republic, setting the stage for the Second Great Awakening in the late 1790s.[30] In the early stages, evangelicals in the South, such as Methodists and Baptists, preached for religious freedom and abolition of slavery; they converted many slaves and recognized some as preachers.

Government

Main article: Colonial government in the Thirteen Colonies

Each of the 13 American colonies had a slightly different governmental structure. Typically, a colony was ruled by a governor appointed from London who controlled the executive administration and relied upon a locally elected legislature to vote on taxes and make laws. By the 18th century, the American colonies were growing very rapidly as a result of low death rates along with ample supplies of land and food. The colonies were richer than most parts of Britain, and attracted a steady flow of immigrants, especially teenagers who arrived as indentured servants.[31]

Servitude and slavery

Over half of all European immigrants to Colonial America arrived as indentured servants.[32] Few could afford the cost of the journey to America, and so this form of unfree labor provided a means to immigrate. Typically, people would sign a contract agreeing to a set term of labor, usually four to seven years, and in return would receive transport to America and a piece of land at the end of their servitude. In some cases, ships' captains received rewards for the delivery of poor migrants, and so extravagant promises and kidnapping were common. The Virginia Company and the Massachusetts Bay Company also used indentured servant labor.[7]

The first African slaves were brought to Virginia[33] in 1619,[34] just twelve years after the founding of Jamestown. Initially regarded as indentured servants who could buy their freedom, the institution of slavery began to harden and the involuntary servitude became lifelong[34] as the demand for labor on tobacco and rice plantations grew in the 1660s.[citation needed] Slavery became identified with brown skin color, at the time seen as a "black race", and the children of slave women were born slaves (partus sequitur ventrem).[34] By the 1770s African slaves comprised a fifth of the American population.

The question of independence from Britain did not arise as long as the colonies needed British military support against the French and Spanish powers. Those threats were gone by 1765. However, London continued to regard the American colonies as existing for the benefit of the mother country in a policy known as mercantilism.[31]

Colonial America was defined by a severe labor shortage that used forms of unfree labor, such as slavery and indentured servitude. The British colonies were also marked by a policy of avoiding strict enforcement of parliamentary laws, known as salutary neglect. This permitted the development of an American spirit distinct from that of its European founders.[35]

Road to independence

Map of the British and French settlements in North America in 1750, before the French and Indian War

An upper-class emerged in South Carolina and Virginia, with wealth based on large plantations operated by slave labor. A unique class system operated in upstate New York, where Dutch tenant farmers rented land from very wealthy Dutch proprietors, such as the Van Rensselaer family. The other colonies were more egalitarian, with Pennsylvania being representative. By the mid-18th century Pennsylvania was basically a middle-class colony with limited respect for its small upper-class. A writer in the Pennsylvania Journal in 1756 summed it up:

The People of this Province are generally of the middling Sort, and at present pretty much upon a Level. They are chiefly industrious Farmers, Artificers or Men in Trade; they enjoy in are fond of Freedom, and the meanest among them thinks he has a right to Civility from the greatest.[36]

Political integration and autonomy

Join, or Die: This 1756 political cartoon by Benjamin Franklin urged the colonies to join together during the French and Indian War.

The French and Indian War (1754–63), part of the larger Seven Years' War, was a watershed event in the political development of the colonies. The influence of the French and Native Americans, the main rivals of the British Crown in the colonies and Canada, was significantly reduced and the territory of the Thirteen Colonies expanded into New France, both in Canada and Louisiana. The war effort also resulted in greater political integration of the colonies, as reflected in the Albany Congress and symbolized by Benjamin Franklin's call for the colonies to "Join, or Die". Franklin was a man of many inventions – one of which was the concept of a United States of America, which emerged after 1765 and would be realized a decade later.[37]

Taxation without representation

Following Britain's acquisition of French territory in North America, King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, with the goal of organizing the new North American empire and protecting the Native Americans from colonial expansion into western lands beyond the Appalachian Mountains. In the following years, strains developed in the relations between the colonists and the Crown. The British Parliament passed the Stamp Act of 1765, imposing a tax on the colonies, without going through the colonial legislatures. The issue was drawn: did Parliament have the right to tax Americans who were not represented in it? Crying "No taxation without representation", the colonists refused to pay the taxes as tensions escalated in the late 1760s and early 1770s.[38]

An 1846 painting of the 1773 Boston Tea Party.

The population density in the American Colonies in 1775.

The Boston Tea Party in 1773 was a direct action by activists in the town of Boston to protest against the new tax on tea. Parliament quickly responded the next year with the Intolerable Acts, stripping Massachusetts of its historic right of self-government and putting it under military rule, which sparked outrage and resistance in all thirteen colonies. Patriot leaders from every colony convened the First Continental Congress to coordinate their resistance to the Intolerable Acts. The Congress called for a boycott of British trade, published a list of rights and grievances, and petitioned the king to rectify those grievances.[39] This appeal to the Crown had no effect, though, and so the Second Continental Congress was convened in 1775 to organize the defense of the colonies against the British Army.

Common people became insurgents against the British even though they were unfamiliar with the ideological rationales being offered. They held very strongly a sense of "rights" that they felt the British were deliberately violating – rights that stressed local autonomy, fair dealing, and government by consent. They were highly sensitive to the issue of tyranny, which they saw manifested by the arrival in Boston of the British Army to punish the Bostonians. This heightened their sense of violated rights, leading to rage and demands for revenge, and they had faith that God was on their side.[40]

American Revolution

Main articles: American Revolution and History of the United States (1776–1789)

See also: Commemoration of the American Revolution

The American Revolutionary War began at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts in April 1775 when the British tried to seize ammunition supplies and arrest the Patriot leaders. In terms of political values, the Americans were largely united on a concept called Republicanism, which rejected aristocracy and emphasized civic duty and a fear of corruption. For the Founding Fathers, according to one team of historians, "republicanism represented more than a particular form of government. It was a way of life, a core ideology, an uncompromising commitment to liberty, and a total rejection of aristocracy."[41]

MENU0:00

Reading of The Declaration of Independence originally written by Thomas Jefferson, presented on July 4, 1776.

Washington's surprise crossing of the Delaware River in December 1776 was a major comeback after the loss of New York City; his army defeated the British in two battles and recaptured New Jersey.

The Thirteen Colonies began a rebellion against British rule in 1775 and proclaimed their independence in 1776 as the United States of America. In the American Revolutionary War (1775–83) the Americans captured the British invasion army at Saratoga in 1777, secured the Northeast and encouraged the French to make a military alliance with the United States. France brought in Spain and the Netherlands, thus balancing the military and naval forces on each side as Britain had no allies.[42]

George Washington

General George Washington (1732–99) proved an excellent organizer and administrator who worked successfully with Congress and the state governors, selecting and mentoring his senior officers, supporting and training his troops, and maintaining an idealistic Republican Army. His biggest challenge was logistics, since neither Congress nor the states had the funding to provide adequately for the equipment, munitions, clothing, paychecks, or even the food supply of the soldiers.

As a battlefield tactician, Washington was often outmaneuvered by his British counterparts. As a strategist, however, he had a better idea of how to win the war than they did. The British sent four invasion armies. Washington's strategy forced the first army out of Boston in 1776, and was responsible for the surrender of the second and third armies at Saratoga (1777) and Yorktown (1781). He limited the British control to New York City and a few places while keeping Patriot control of the great majority of the population.[43]

Loyalists and Britain

John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence (1819)

The Loyalists, whom the British counted upon heavily, comprised about 20% of the population but suffered weak organization. As the war ended, the final British army sailed out of New York City in November 1783, taking the Loyalist leadership with them. Washington unexpectedly then, instead of seizing power for himself, retired to his farm in Virginia.[43] Political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset observes, "The United States was the first major colony successfully to revolt against colonial rule. In this sense, it was the first 'new nation'."[44]

Declaration of Independence

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, declared the independence of the colonies by adopting the resolution from Richard Henry Lee, that stated:

That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved; that measures should be immediately taken for procuring the assistance of foreign powers, and a Confederation be formed to bind the colonies more closely together.

On July 4, 1776 they adopted the Declaration of Independence and this date is celebrated as the nation's birthday. On September 9 of that year, Congress officially changed the nation's name to the United States of America. Until this point, the nation was known as the "United Colonies of America".[45]

The new nation was founded on Enlightenment ideals of liberalism and what Thomas Jefferson called the unalienable rights to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness". It was dedicated strongly to republican principles, which emphasized that people are sovereign (not hereditary kings), demanded civic duty, feared corruption, and rejected any aristocracy.[46]

Early years of the republic

Main article: History of the United States (1789–1849)

See also: First Party System and Second Party System

Confederation and Constitution

MENU0:00

Reading of the United States Constitution of 1787

Further information: Articles of Confederation and History of the United States Constitution

Economic growth in America per capita income. Index with 1700 set as 100.

In the 1780s the national government was able to settle the issue of the western regions of the young United States, which were ceded by the states to Congress and became territories. With the migration of settlers to the Northwest, soon they became states. Nationalists worried that the new nation was too fragile to withstand an international war, or even internal revolts such as the Shays' Rebellion of 1786 in Massachusetts.[47]

Nationalists – most of them war veterans – organized in every state and convinced Congress to call the Philadelphia Convention in 1787. The delegates from every state wrote a new Constitution that created a much more powerful and efficient central government, one with a strong president, and powers of taxation. The new government reflected the prevailing republican ideals of guarantees of individual liberty and of constraining the power of government through a system of separation of powers.[47]

The Congress was given authority to ban the international slave trade after 20 years (which it did in 1807). A compromise gave the South Congressional apportionment out of proportion to its free population by allowing it to include three-fifths of the number of slaves in each state's total population. This provision increased the political power of southern representatives in Congress, especially as slavery was extended into the Deep South through removal of Native Americans and transportation of slaves by an extensive domestic trade.

To assuage the Anti-Federalists who feared a too-powerful national government, the nation adopted the United States Bill of Rights in 1791. Comprising the first ten amendments of the Constitution, it guaranteed individual liberties such as freedom of speech and religious practice, jury trials, and stated that citizens and states had reserved rights (which were not specified).[48]

President George Washington

George Washington legacy remains among the two or three greatest in American history, as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, hero of the Revolution, and the first President of the United States.

MENU0:00

Reading of the Farewell address of President George Washington, 1796

George Washington – a renowned hero of the American Revolutionary War, commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, and president of the Constitutional Convention – became the first President of the United States under the new Constitution in 1789. The national capital moved from New York to Philadelphia in 1790 and finally settled in Washington DC in 1800.

The major accomplishments of the Washington Administration were creating a strong national government that was recognized without question by all Americans.[49] His government, following the vigorous leadership of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, assumed the debts of the states (the debt holders received federal bonds), created the Bank of the United States to stabilize the financial system, and set up a uniform system of tariffs (taxes on imports) and other taxes to pay off the debt and provide a financial infrastructure. To support his programs Hamilton created a new political party – the first in the world based on voters – the Federalist Party.

Two-party system

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison formed an opposition Republican Party (usually called the Democratic-Republican Party by political scientists). Hamilton and Washington presented the country in 1794 with the Jay Treaty that reestablished good relations with Britain. The Jeffersonians vehemently protested, and the voters aligned behind one party or the other, thus setting up the First Party System.

Depiction of election-day activities in Philadelphia by John Lewis Krimmel, 1815

Federalists promoted business, financial and commercial interests and wanted more trade with Britain. Republicans accused the Federalists of plans to establish a monarchy, turn the rich into a ruling class, and making the United States a pawn of the British.[50] The treaty passed, but politics became intensely heated.[51]

Challenges to the federal government

Serious challenges to the new federal government included the Northwest Indian War, the ongoing Cherokee–American wars, and the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion, in which western settlers protested against a federal tax on liquor. Washington called out the state militia and personally led an army against the settlers, as the insurgents melted away and the power of the national government was firmly established.[52]

Washington refused to serve more than two terms – setting a precedent – and in his famous farewell address, he extolled the benefits of federal government and importance of ethics and morality while warning against foreign alliances and the formation of political parties.[53]

John Adams, a Federalist, defeated Jefferson in the 1796 election. War loomed with France and the Federalists used the opportunity to try to silence the Republicans with the Alien and Sedition Acts, build up a large army with Hamilton at the head, and prepare for a French invasion. However, the Federalists became divided after Adams sent a successful peace mission to France that ended the Quasi-War of 1798.[50][54]

Increasing demand for slave labor

Main article: Slavery in the United States

Slaves Waiting for Sale: Richmond, Virginia. Painted upon the sketch of 1853

During the first two decades after the Revolutionary War, there were dramatic changes in the status of slavery among the states and an increase in the number of freed blacks. Inspired by revolutionary ideals of the equality of men and influenced by their lesser economic reliance on slavery, northern states abolished slavery.

States of the Upper South made manumission easier, resulting in an increase in the proportion of free blacks in the Upper South (as a percentage of the total non-white population) from less than one percent in 1792 to more than 10 percent by 1810. By that date, a total of 13.5 percent of all blacks in the United States were free.[55] After that date, with the demand for slaves on the rise because of the Deep South's expanding cotton cultivation, the number of manumissions declined sharply; and an internal U.S. slave trade became an important source of wealth for many planters and traders.

In 1807, Congress severed the US's involvement with the Atlantic slave trade.[56]

Louisiana and republicanism under Jefferson

Jefferson saw himself as a man of the frontier and a scientist; he was keenly interested in expanding and exploring the West.

Jefferson's major achievement as president was the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, which provided U.S. settlers with vast potential for expansion west of the Mississippi River.[57]

Jefferson, a scientist himself, supported expeditions to explore and map the new domain, most notably the Lewis and Clark Expedition.[58] Jefferson believed deeply in republicanism and argued it should be based on the independent yeoman farmer and planter; he distrusted cities, factories and banks. He also distrusted the federal government and judges, and tried to weaken the judiciary. However he met his match in John Marshall, a Federalist from Virginia. Although the Constitution specified a Supreme Court, its functions were vague until Marshall, the Chief Justice (1801–35), defined them, especially the power to overturn acts of Congress or states that violated the Constitution, first enunciated in 1803 in Marbury v. Madison.[59]

War of 1812

Main article: War of 1812

Territorial expansion; Louisiana Purchase in white.

Thomas Jefferson defeated Adams for the presidency in the 1800 election. Americans were increasingly angry at the British violation of American ships' neutral rights to hurt France, the impressment (seizure) of 10,000 American sailors needed by the Royal Navy to fight Napoleon, and British support for hostile Indians attacking American settlers in the Midwest with the goal of creating a pro-British Indian barrier state to block American expansion westward. They may also have desired to annex all or part of British North America, although this is still heavily debated.[60][61][62][63][64] Despite strong opposition from the Northeast, especially from Federalists who did not want to disrupt trade with Britain, Congress declared war on June 18, 1812.[65]

Oliver Hazard Perry's message to William Henry Harrison after the Battle of Lake Erie began with what would become one of the most famous sentences in American military history: "We have met the enemy and they are ours".[66] This 1865 painting by William H. Powell shows Perry transferring to a different ship during the battle.

The war was frustrating for both sides. Both sides tried to invade the other and were repulsed. The American high command remained incompetent until the last year. The American militia proved ineffective because the soldiers were reluctant to leave home and efforts to invade Canada repeatedly failed. The British blockade ruined American commerce, bankrupted the Treasury, and further angered New Englanders, who smuggled supplies to Britain. The Americans under General William Henry Harrison finally gained naval control of Lake Erie and defeated the Indians under Tecumseh in Canada,[67] while Andrew Jackson ended the Indian threat in the Southeast. The Indian threat to expansion into the Midwest was permanently ended. The British invaded and occupied much of Maine.

The British raided and burned Washington, but were repelled at Baltimore in 1814 – where the "Star Spangled Banner" was written to celebrate the American success. In upstate New York a major British invasion of New York State was turned back at the Battle of Plattsburgh. Finally in early 1815 Andrew Jackson decisively defeated a major British invasion at the Battle of New Orleans, making him the most famous war hero.[68]

With Napoleon (apparently) gone, the causes of the war had evaporated and both sides agreed to a peace that left the prewar boundaries intact. Americans claimed victory on February 18, 1815 as news came almost simultaneously of Jackson's victory of New Orleans and the peace treaty that left the prewar boundaries in place. Americans swelled with pride at success in the "second war of independence"; the naysayers of the antiwar Federalist Party were put to shame and the party never recovered. Britain never achieved the war goal of granting the Indians a barrier state to block further American settlement and this allowed settlers to pour into the Midwest without fear of a major threat.[68] The War of 1812 also destroyed America's negative perception of a standing army, which was proved useful in many areas against the British as opposed to ill-equipped and poorly-trained militias in the early months of the war, and War Department officials instead decided to place regular troops as the nation's main defense.[69]

Second Great Awakening

Main article: Second Great Awakening

A drawing of a Protestant camp meeting, 1829.

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant revival movement that affected the entire nation during the early 19th century and led to rapid church growth. The movement began around 1790, gained momentum by 1800, and, after 1820 membership rose rapidly among Baptist and Methodist congregations, whose preachers led the movement. It was past its peak by the 1840s.[70]

It enrolled millions of new members in existing evangelical denominations and led to the formation of new denominations. Many converts believed that the Awakening heralded a new millennial age. The Second Great Awakening stimulated the establishment of many reform movements – including abolitionism and temperance designed to remove the evils of society before the anticipated Second Coming of Jesus Christ.[71]

Era of Good Feelings

Main article: Era of Good Feelings

Era of Good Feelings

As strong opponents of the war, the Federalists held the Hartford Convention in 1814 that hinted at disunion. National euphoria after the victory at New Orleans ruined the prestige of the Federalists and they no longer played a significant role as a political party.[72] President Madison and most Republicans realized they were foolish to let the Bank of the United States close down, for its absence greatly hindered the financing of the war. So, with the assistance of foreign bankers, they chartered the Second Bank of the United States in 1816.[73][74]

Settlers crossing the Plains of Nebraska.

The Republicans also imposed tariffs designed to protect the infant industries that had been created when Britain was blockading the U.S. With the collapse of the Federalists as a party, the adoption of many Federalist principles by the Republicans, and the systematic policy of President James Monroe in his two terms (1817–25) to downplay partisanship, the nation entered an Era of Good Feelings, with far less partisanship than before (or after), and closed out the First Party System.[73][74]

The Monroe Doctrine, expressed in 1823, proclaimed the United States' opinion that European powers should no longer colonize or interfere in the Americas. This was a defining moment in the foreign policy of the United States. The Monroe Doctrine was adopted in response to American and British fears over Russian and French expansion into the Western Hemisphere.[75]

In 1832, President Andrew Jackson, 7th President of the United States, ran for a second term under the slogan "Jackson and no bank" and did not renew the charter of the Second Bank of the United States of America, ending the Bank in 1836.[76] Jackson was convinced that central banking was used by the elite to take advantage of the average American, and instead implemented state banks, popularly known as "pet banks".[76]

Westward expansion

Indian removal

Main article: Indian removal

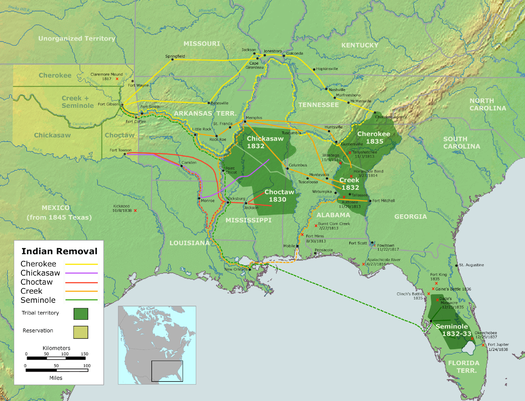

The Indian Removal Act resulted in the transplantation of several Native American tribes and the Trail of Tears.

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the president to negotiate treaties that exchanged Native American tribal lands in the eastern states for lands west of the Mississippi River.[77] Its goal was primarily to remove Native Americans, including the Five Civilized Tribes, from the American Southeast; they occupied land that settlers wanted. Jacksonian Democrats demanded the forcible removal of native populations who refused to acknowledge state laws to reservations in the West; Whigs and religious leaders opposed the move as inhumane. Thousands of deaths resulted from the relocations, as seen in the Cherokee Trail of Tears.[78] The Trail of Tears resulted in approximately 2,000–8,000 of the 16,543 relocated Cherokee perishing along the way.[79][80] Many of the Seminole Indians in Florida refused to move west; they fought the Army for years in the Seminole Wars.

I'll be expanding on Cherokee history and language on my blog. Nice article!