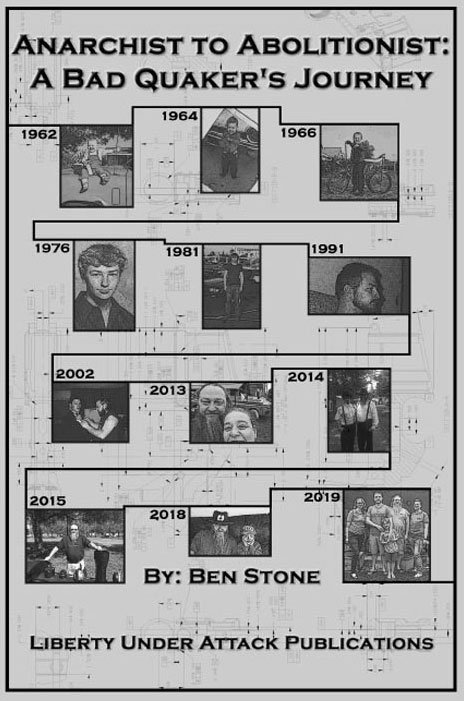

Anarchist to Abolitionist: A Bad Quaker's Journey

An Appalachian Tale

Executive Order 6102

From Wikipedia:

Executive Order 6102 is a United States presidential executive order signed on April 5, 1933, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt "forbidding the hoarding of gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates within the continental United States".

Essentially, 6102 forbid the private ownership of gold in any form other than jewelry or raw ore. Everything else had to be turned over to the government, or you faced a penalty of $10,000 and/or up to ten years imprisonment. Gold was $20 an ounce at the time. Today, it hovers around $1,200 an ounce. That means that a $10,000 fine in 1933, adjusted for inflation, is $600,000 today.

Also, notice the wording of 6102. If you were rich, you could simply move your gold off shore and you were immune to 6102. Therefore, this order excluded the rich. And, of course, the poor had no gold. 6102 was aimed at the newly formed middle class, and was a direct robbery of their meager wealth.

My understanding is that, in 1933, the United States government was broke and a payment to the Rothschild banks was soon coming due, in gold. Members of the Rothschild family, by way of J.P. Morgan, loaned the US Treasury vast amounts of gold in and around 1895 on what was basically a twenty year note. In 1913, the US government saw that there was no way they could make the payment, so through some tricky maneuvers at a place called Jekyll Island, the Federal Reserve Bank, owned by the Rothschilds, came into existence. But that only put the Rothschilds in control of America's banking system, it didn't pay back the gold, meaning that in another twenty years, the payment would be due again. It's a long story and if you haven't researched it, you probably won't believe it even if I tell it here, so there is no point in going any further on that topic

However, I can tell you about my grandfather, John Brown

My mother's father's name was John Brown. He wasn't that brave abolitionist from the nineteenth century; he was a farmer and a merchant in Appalachia during the first half of the 20th century. My family called him Poppy.

Poppy had a small farm in eastern Kentucky. Together with Mawmaw, they had a small general store that she ran.

Poppy would get up early in the morning and get the boys out to do their chores on the farm. Poppy and Mawmaw had twelve children, two girls and ten boys, one of which died as a child. Once the chores were done and breakfast was had, Poppy would load up his wagon with store supplies and farm goods and begin his rounds. I don't know how often he made his rounds, but this is a basic outline.

Poppy would drive his wagon from farm to farm, asking what they had to sell and what they needed to trade for, or what they needed to buy. If he had what they needed, he would sell it to them or trade for something they had, or if he didn't have it, he would note their order and bring it back another day. No one was in a hurry back then. People knew how to plan ahead and how to wait, a skill long lost on current generations.

Eventually, Poppy's route would land him in the little town of South Shore, Kentucky, where he would stop at the local mercantile and sell some of his goods, while filling the orders he had collected on his route. Poppy did this for years, and supplied goods to Appalachian farm families, while providing for his own family. He also turned a modest profit.

Poppy was wise, even in his youth. When he was a young man, he began saving for his old age. Anytime he could collect a $20 gold coin, he would stash it in a nail keg he kept hidden away. For years and years, he would slip a gold coin in that keg every chance he got. By 1933, that keg was full, and, unfortunately, Mawmaw found it.

Wikimedia

A nail keg was about 18" tall and about 13" wide, meaning it could hold about one hundred pounds of nails, and slightly over that weight in gold coins. Let's assume Poppy's full nail keg weighed one hundred pounds, just to make the numbers easy. Also, let's not worry about the tiny difference between troy ounces and pounds to common ounces and pounds, or that the gold coins weren't .999 pure. Let's just say Poppy had one hundred pounds of gold. It may have been more or it may have been less, but in today's dollars that's in the neighborhood of $1,920,000. Pause and let that soak in. At the time, it was worth about $32,000 in face value. That's how inflation works. The bankers and the government devalue your money and steal its value through inflation, and the public is too distracted to notice. That's why gold had to be taken from the middle class; it holds its value, while the dollar loses value. Things don't get more expensive, the dollar becomes less and less valuable, and that is intentional. Inflation is a form of taxation.

Mawmaw was terrified! What if someone found out they had that much gold in their house? People would kill for that kind of money. After all, this was Appalachia during the Great Depression. Then there was the matter of this new law. The money had to be taken to a bank and exchanged for paper dollars before the government men came to get it.

Poppy hated Roosevelt. What gave Roosevelt the right to take Poppy's gold? Nothing, that's what right Roosevelt had to Poppy's gold! But Roosevelt was a thief and thieves do what thieves do.

Poppy figured Mawmaw was probably right. On Poppy's next round to South Shore, he would get on the ferry boat and cross the river to Portsmouth. He had never had any dealings with a bank because, you know, bankers are thieves. But he had to obey the law because, well, it's the law.

Poppy walked into a bank, past the armed guard at the door, and stood in line. Lots of people seemed to be pulling their money out of this bank and Poppy had no idea why. When it was Poppy's turn, he sat the nail barrel up on the counter and asked to exchange it for paper dollars.

The teller was a bit taken aback, as you might expect, and asked for the bank president to come help. The bank president explained that they could only hand out $200 over the counter to anyone, under any circumstances. This was a banking rule set up to stop the "bank runs" that destroyed so many banks after the stock market crash a few years earlier.

Well fine, then! Poppy would just have to exchange $200 at this bank and then go exchange another $200 at another bank. This will take all day, traveling around Portsmouth, going from bank to bank, but it was the law, after all.

The banker explained that it didn't work that way. The deadline to trade in gold was past and the guard wouldn't let Poppy leave with the government's gold.

THE GOVERNMENT'S GOLD? This was Poppy's gold! The government didn't work and starve and sweat and bleed for this gold! Poppy had! The calluses were on Poppy's hands, not some government man with a gun!

The armed guard didn't seem to see Poppy's point. But the banker had a solution. Poppy could deposit the whole amount, all $32,000 of it, then withdraw $200 in paper cash. The remainder could either be safely left at the bank to collect interest, or he could withdraw some each time he came to town.

Poppy didn't like any of this, but what choice did he have? So, he handed over the gold and they gave him a wad of paper and a little book with a stamp on it.

It was a little while, maybe a week or more, before his rounds brought him back to town. Poppy boarded the ferry boat and crossed over to Portsmouth. He walked to the bank and read the big sign on the door. No matter the efforts to stop a bank run, it happened anyway, and the bank had been closed. Just like that Poppy's money was gone.

Franklin Roosevelt was a banker and he was a government man, in other words a thief his whole life.

Poppy died in 1955, six years before I was born. When he died, he had his farm and a little church he had built with his own hands. The day he finished the roof of the church, he walked back to his house where Mawmaw had his dinner ready. He wasn't feeling very good, so he told her he thought he would skip the meal for now. Then his heart stopped and Poppy was gone.

Mawmaw saw to it that the church was in proper hands, then she sold the farm and moved in with my mother and father. She lived with my family about twenty years.

One evening, the members of that same church were having a business meeting to decide to keep the old traditions, or bring in a new preacher, who would update things and take the church in a new direction. Mawmaw made sure she was there in attendance, and when the proper time came, she stood to address the congregation. I wasn’t there that night, so I can’t say what she told them, but I imagine she encouraged them to hold to the old ways. Whatever she said, I’m sure she put every ounce of her heart into it. When she was completely finished and had said her peace, she sat down and closed her eyes. Then, Mawmaw was gone.

A Story About Nothing, Final Thoughts, and Suggested Reading

First post & table of contents

If you would like to read the book in its entirety, you can purchase it with cryptocurrency at Liberty Under Attack Publications or find it on Amazon. We also invite you to visit BadQuaker.com, and, as always, thank you for reading.