The thrilling and true story of the Batavia

On October 29, 1628, the commander and chief merchant of the Dutch-East-India Company - Francisco Pelsaert - gave the sign to hoist the anchor and the sails of the Batavia. Now, the maiden voyage of the ship to the Far East would begin. When it left the Dutch Island of Texel, it had over three hundred crew on board, and an eight-month journey spanning 15,000 nautical miles ahead. The journey would take them to foreign shores and unknown seas.

Replica of the Batavia

Stories about sailors and soldiers near the equator succumbing to the scorching heat, extreme thirst and stormy seas circulate on the ship. Despite these stories, they decide to go. Some seek adventure and want to flee the routine of everyday life. Others have growing debt and prefer the hardships of ship life over the miserable existence at home. They all hope for a prosperous voyage, with the ship Batavia bringing them safely to similar named city built by the Dutch East India Company on the island Java.

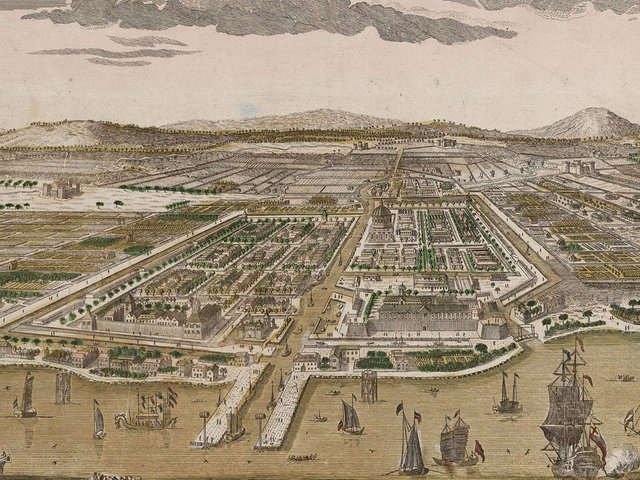

The City of Batavia and the fort on Java.

But things will go differently: seven months after the departure of the - would be - proud flagship of the VOC, not many will be left.

The night before the fateful events on June 4, 1629, the captain, Adriaen Jacobszoon, stood on guard. Hitherto, the trip was progressing well. They had passed the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, and the skipper and his mates had decided to take an easterly course. The dangerous reefs off the coast of Southern Lands, which each skipper fears, were still far away according to Adriaen Jacobszoon. He saw the glowing foam in the distance as merely a reflection of the moonlight. Just before he was to exchange guard duty, a huge blow woke all passengers from their sleep. The skipper was convinced that nothing was seriously wrong and believed that the ship was only stranded on a shoal, similar to the sand banks in the Dutch waters. He therefore ordered to cast out the anchor at the back, hoping to reinvigorate the ship at high tide. But high tide never came, the tide dropped and it became clear that the skipper had made a big mistake: the ship had for too long held an easterly course and had sailed to the dreaded "Houtman drooghten". To make matters worse, a storm began: Against this brute force of nature, not a ship could withstand. After a few hours, the stern of the ship broke in half, and the ship was wrecked.

The Batavia stuck on the reef.

The time for bringing the passengers to safety was running out. Various islands in the vicinity of the wreck were not covered by the sea at high tide. Using the lifeboat and a smaller boat, the castaways were brought ashore. Francisco Pelsaert was the one who was responsible for the welfare of the crew and passengers aboard the Batavia. As chief merchant, moreover, his main task was to protect the material interests of the Dutch East India Company. On board were precious goods such as cash boxes and the box with the jewels with which the Company would pay for the purchase of its merchandise.

How heavily the commercial interests on the ships of the Company weighed, is proven by the fact that the chief merchant - and not the skipper - represented the highest authority on board. Aboard a Dutch fluyt ship, on which more than three hundred people had to live and work together for months, it was vital that there was a strict hierarchy and strict discipline. Pelsaert was not quite coped for this task. During the trip, he was often sick and slept in his cabin, leaving a lot of the responsibility to the skipper and his other subordinates.

Even if circumstances demanded it, Pelsaert did not show any bold governing behavior. Namely, before the ship reached the Cape of Good Hope, an incident had occurred. The skipper had his eye on one of the young female passengers, named Lucretia Jans, and was so attracted to the young woman that it had not gone unnoticed on the ship. However, Lucretia was not impressed by the advances of Adriaen Jacobszoon. The skipper didn't like this, and could not swallow it so easily. He retaliated on her by ordering a group of sailors to drag Lucretia out of bed and smear her with tar, to pay for her rejection of the skipper. Francisco Pelsaert had been aware of this incident, but with only a few remarks to the skipper, he had dismissed the case. His limp performance finally avenged itself on the wreck of the Batavia. When Pelsaert ordered a group of soldiers and sailors to recover the cargo and cash from the wreck, they flatly refused this. They saw an opportunity and went on to enjoy the gin and wine, instead of risking their lives for the salvage of the cargo. Pelsaert lacked the authority to get this 'godless, unruly bunch of soldiers and sailors' back into line.

The counting of survivors started: of the 341 persons on board, there were forty who drowned during the storm. 220 castaways were saved and taken to the two islands with only 20 barrels of bread and some barrels of water. The rest of the crew, including the under-merchant in chief Jerome Corneliszoon, were still on the wreck, drunk or not. An uncertain future awaited the survivors of the disaster. The little amount of rainwater they got was collected in tarps, and divided among the many castaways. Another source of drinking water was non-existent on the islands. In desperation, those who could not control their thirst drank water from the sea. As a result, twenty adults and nine children died. Using rinsed wood and other materials on land, the survivors built rudimentary shelters to protect them from the hot sun. The main component of their meals would henceforth consist of seafood.

Under the castaways were a large number of passengers, such as the eight-member family of pastor Bastiaens and the wives and children of soldiers and senior crew members. Lucretia Jans, the woman who was harassed by the skipper, had undertaken the long voyage to enter into marriage with Boudewijn van der Miles, junior merchant in the Batavia Castle on Java for the Company. There were seasoned sailors, craftsmen and senior officers on the ship, but also boys who had gone on the sea for the first time. Like the others, they could only save their lives. Of their meager possessions they had, nothing remained. All passengers, sailors and soldiers knew they had to survive, but also knew that their chances of survival were slight without adequate drinking water.

The day after the stranding, Francisco Pelsaert lead a group of people on the lifeboat in search of drinking water else where. Except for brackish water on surrounding islands and a brief encounter on the mainland with the original inhabitants of Australia, this quest did not succeed. Instead of returning to the other castaways on the islands, they decided to take the occupants of the lifeboat on a long and risky journey to Java. They knew that help from the Batavia Castle might be the only salvation for those left behind. Other motives may have played a role in their decision not to return. It was no coincidence that including Pelsaert, the senior officers, and the rest of the ships elite were on the lifeboat. Did they only care about saving themselves? Either way, Francisco Pelsaert did nothing to prevent the crew and castaways left behind from having to fend for themselves. The occupants of the boat with him, as he would later write in a report, had forced him not to return to those left behind. However, those left behind waited in vain for their return, looking at the horizon, and the conclusion that the 'the rats left the sinking ship' quickly took hold among them. Eventually, Francisco Pelsaert and 48 fellow travelers succeeded to make the long trip by boat and reach the city of Batavia on Java.

More than two months later, Pelsaert went out on a rescue mission on the ship Saerdam. But for many, the rescue came too late. Not the lack of water had caused their death, but rather the chaos and mutiny on the two islands. During those two months, undermerchant Jerome Corneliszoon had emerged as the leader of a mutinous gang consisting of a bunch of soldiers, who exercised a reign of terror over the women, children and other castaways on the Island. Many of the castaways were brutally murdered or raped.

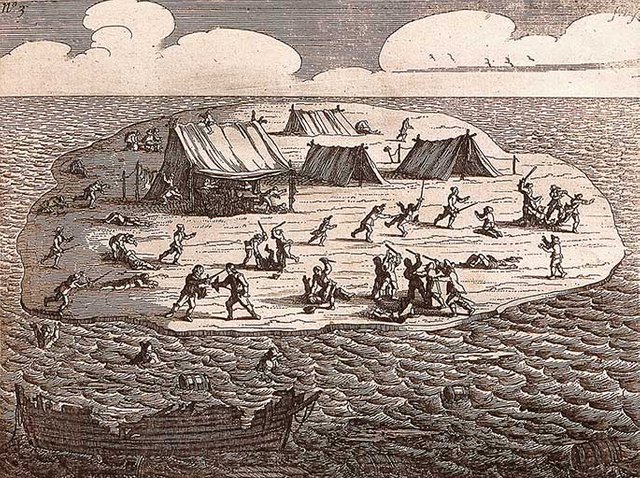

Corneliszoon's gang murdering and raping the castaways.

Before the murders happened, Corneliszoon ordered a group of soldiers led by Wiebbe Hayes to the nearby West Wallabi Island, under the false pretense of searching for water. Once there, they were ordered to light signal fires if they found water so they could then be rescued. Corneliszoon was convinced that they would be unsuccessful, and he left them there to die.

Although Cornelisz had left the soldiers led by Wiebbe Hayes to die, they actually found good sources of food and water on the island. Initially, Wiebbe and his men were unaware of what was taking place on the other island and they sent pre-arranged smoke signals to announce their discovery of food. But after a while, they learned of the massacres from survivors fleeing Cornelisz' island. As a result, the soldiers constructed madeshift weapons, set a watch and built a small fort out of limestone and coral blocks.

A statue of Wiebbe Hayes

When Cornelisz heard about the news of water and food on the other island, he went there with his men to try and defeat Wiebbe Hayes and his group. However, Wiebbe Hayes and his soldiers were much better fed than the mutineers and they easily defeated them in several battles, taking Cornelisz hostage. The mutineers who escaped, reorganized under a man named Wouter Loos and tried to attack Wiebbe Hayes again, this time using muskets to besiege the small makeshift fort. They almost defeated the soldiers, but Wiebbe Hayes and his men prevailed.

The remnants of the makeshift fort built by Wiebbe Hayes and his men on the West Wallabi island still stand to this day.

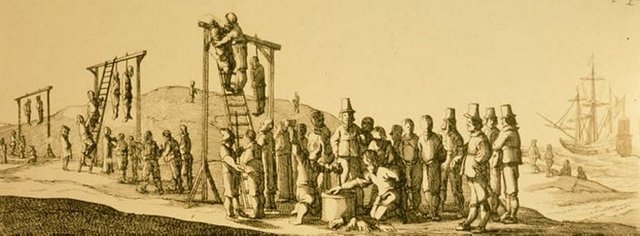

When the Saerdam ship and Francisco Pelsaert returned, Wiebbe Hayes and his soldiers managed to arrive there first and explain to Pelsaert what happened. Pelsaert and his soldiers later on captured the mutinous gang. He personally listened to the words of the mutineers and witnesses. By torture and confrontations he found out what had happened during his absence. Pelsaert ordered sentences on spot for the murder of so many innocent and for mutiny. The captain Jerome Corneliszoon and seven of his henchmen were hanged. Some of those sentenced had their hands cut off before they were hanged. Others penalties were keelhauling or whipping. On the journey back to Batavia, two mutineers where dropped off on the mainland of Australia and left to fend for themselves. They can be regarded as the first, albeit involuntary, Dutch immigrants and European settlers of Australia.

Pelsaert ordering the sentences of the mutineers and murderers.

Of the 341 people on board, only 68 men, seven women and two children survived the disaster. Lucretia admittedly arrived in Batavia, but her to-be husband had deceased. A year later she married Jacob Corneliszoon Cuick, sergeant of the army of the Dutch East India Company in Batavia City. Of the clergyman's family, only the minister himself and one of his daughters turned back. Pelsaert was later appointed to a high office in Batavia, but certainly he did not enjoy his promotion. In 1630 he died at the age of 35.

Very informative, up and followed!