CRIME AND JUSTICE IN ANCIENT GREECE

CRIME AND JUSTICE IN ANCIENT GREECE

Socrates death

Poisoning was a common way of murdering people. King Mithridates VI of Pontus was obsessed with the idea of being assassinated by poison. In an efforts to create a defense against such attacks he took minute amounts of toxins to be build up a tolerance to them and developed a complex compound---called methridatium---comprised of 54 toxins, which was taken by him took regularly and leaders after him who feared assassinations.

According to a myth, Medea murdered the uncle of Jason (of the Argonauts fame) by giving him a bath in a deadly poison that the king thought was going to restore his lost youth. Agamemnon was also murdered in a bathtub. His wife struck him twice on the head with an ax after he returned home from the Trojan War."

Laws varied from city to city state. The scholar John Gager, told National Geographic, "With the possible exception of modern America, no society has been more notorious for litigation than classical Athens. Women were not normally allowed to testify in Athenian courts.

In ancient times men sometimes made a pledge by putting their hands on their testicles as if to say, "If I am lying you can cut off my balls." The practice of making a pledge on the Bible is said to have its roots in this practice.

See Curse Tablets Under Superstitions Under Religion

Ancient Greek Citizens

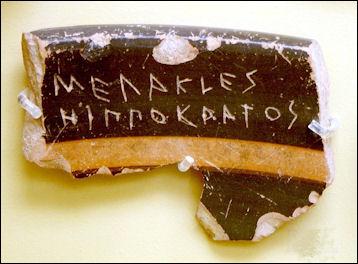

Ostrakon Megacles

Beginning in the 7th century B.C., ordinary people were freed from the bonds of slavery, debt and serfdom to wealthy aristocrats. "I took away the mortgage stones stuck in earth's breast," wrote Solon. “And she, who was a slave before, is now free."

Most Greek citizens were landowners although the criteria for citizenship varied from city-state to city-state. In Sparta citizens had to be at least thirty and unanimously approved by the existing citizenry. Some states were democracies where citizens voted for city-state magistrates and passed laws. Other were oligarchies or constitutional governments.

Citizens had the right to vote, express their opinions, and participate in policy decisions in the assembly on matters like taxation and war. In wartime citizens were expected to serve as soldiers. In peacetime they were obliged to show up and serve as members of the assembly and as judges. Any citizen who was over 30 could run for office. Women and slaves were not allowed to be citizens. Citizenship was inherited by offspring of two Athenian citizens. Private citizens not part of the ruling class were called idiots .

True representative government was something that never occurred to the ancient Greeks. Serfdom was also passed down from generation to generation. Their labor freed the land owners to make war among themselves and establish philosophy and the arts.

Good and Bad Side of Greek Democracy

Ostrakon against Melakles,

son of Hyppokrates Mary Beard wrote in the New Statesman, “In 440BC, a few months after his Antigone won first prize at the Athenian drama festival, Sophocles served as one of the commanding officers of an Athenian task force that sailed off to put down a rebellion on the island of Samos. The inhabitants had decided to break away from Athens's empire - the network of Athenian satellite states spread all over the eastern Mediterranean - and they had to be brought back into the fold. The irony was that a few decades earlier, Athens had led Greece to victory against a vast Persian invasion; now, the Athenians had imposed their own tight control over their former allies (which may have left some wondering whether conquest by the Persians might have been the better option). [Source: Mary Beard, New Statesman, October 14, 2010]

For modern historians with a rose-tinted view of ancient Athenian democracy, the military command of Sophocles counts as a feather in the Athenian cap. The guiding principle of this system was that every citizen should play a full part in political, military and civic life; there were to be no bystanders. By the middle of the 5th century BC, most jobs - from those on the city council to executive officers and juries - were assigned by lot to give everyone an equal chance of running the city. Admittedly, Sophocles's command was one of the very few military offices still assigned by election (not even the Athenians were wide-eyed enough to draw their generals out of a hat), but having a dramatist who was also a general fits nicely with the spirit of their politics. Their slogans were all about equality: citizens were equal in power and equal before the law and had an equal chance of getting their voice heard. None of this is bad, as democratic aspirations go. In fact, most modern political systems could learn something from Athens. But there is a darker side to this democracy. Part of that darkness is well known. Athens may have been a city in which every citizen was equal, but those equal citizens were a tiny minority of the population: perhaps 30,000 men out of 250,000 inhabitants altogether. The vast majority - slaves, women and immigrants - were totally excluded from the political process. Ancient Athenian politics was more an exclusive gentleman's club than a democracy in our terms. Even the autocratic Romans welcomed immigrants more warmly than democratic Athens.

But the case of Sophocles raises other issues. The campaign to regain control of Samos was a brutal piece of imperial control: the local leaders in Samos had wanted to get out of Athens's orbit and the Athenians had wanted to keep them in. Not unlike some sections of the modern United States, Athens might deny an overtly imperialist agenda but it pursued regime change and the imposition of democracy wherever it suited Athenian interests.

Lawyers and Jurors in Ancient Greece

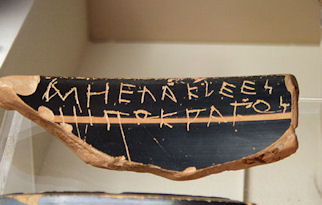

Curse inscription

In the 4th century B.C. , Athenian jurors cast their votes in terra-cotta ballot boxes. The ballots, stamped "official ballot," resembled metal tops. Each juror was given two ballots: a solid one represented innocent and a hollow one represented guilty. The ballots were made in such a way that they could be deposited in the ballot box without any one seeing the juror's choice.

The first lawyers were 5th century B.C. logographoi , professional Athenian speech writers who were trained in rhetoric and used their persuasive powers to write speeches to help defendants argue cases before a magistrate, to prepare the details of the case, to advise their clients which courts to use, and to come up with a strategy. They differed from modern lawyers however in that they didn't argue the cases themselves for their clients.

Describing a young lawyer in action, the satirical dramatist Aristophanes wrote: "We take our stand before the bench...Your youngster opens fire by discharging a verbal volley. Then he drags up some poor Methuselah and cross-examines him, baiting word traps, tearing, snaring and curdling him. The old fellow mumbles through his toothless gums and goes off with his case lost." Describing another lawyer in Clouds , Aristophanes wrote: he was a "lawbook on legs, who can snoop like a beagle,"a double-faced, lethal-tongued legal eagle."

Athenian lawyers used many tactics well-known modern attorneys: They raised innumerable facts and details to bolster their own case and obscure the main points of their opponents arguments; they brought in weeping wives and children to solicit sympathy. A judge in one of Aristophanes plays said: "There isn't a form of flattery they don't pour into a jury's ear. And some try pleading poverty and giving me hard luck stories...Some crack jokes to get me to laugh and forget I've got it in for them. And, if I prove immune to all these, they'll right away drag up their babes by the hand." In the same play a judge hears a case concerning a dog accused of stealing cheese from a kitchen. The dog wins acquittal by bring his yowling pups to the stand.

Draconian Laws and Other Punishment in Ancient Greece

Burning garments were used to punish criminals in ancient Greece and Rome. Plato described gruesome tortures involving tunics soaked in pitch. Many sentenced to death were poisoned. Excavations have revealed thimble-size terra cotta vessels in which executioners measured doses of hemlock.

Draco produced a code of laws for Athens in which some relatively minor crimes were punished with death. His form of absolutism gave birth to the term "Draconian." Draco was popular however. In 590 B.C., so many well wishers showed up to see him in an Athens stadium he was smothered under a mountain of cloaks and hats thrown in by fans.

Trial of Socrates

In Socrates trial there were no lawyers and Socrates defended himself, saying simply he was a humble seeker of truth. One by one his accusers, limited by the time established by a water clock, addressed the 501 member jury. His chief accuser, Meletus, was. Socrates said, “an unknown youth with straight hair and a skimpy beard."

Socrates, then 70 years old, "gave a bumbling performance. He was no orator" said Historian M.I. Finley. In the trial, Socrates said that people were threatened by his self appointed role as "the gadfly of Athens." Socrates's questioning of the existence of the gods, cross-examination of conventional wisdom and criticizing of the government had won him many enemies. Some say he was used as a scapegoat for Athens' loss in the Peloponnesian War.

The jury found Socrates guilty by a vote of 281 to 220 and advocated the death penalty. Socrates was given an opportunity to suggest an alternative punishment. He said he deserved to be treated like an Olympic champion and receive a life-time pension. The jury was not amused and he was sentencing to die by drinking a cup off hemlock.

Accountability, Corruption and Bribes in Ancient Greece

John McK. Campo, a classic professor at Randolph-Macon College in Virginia, wrote in the New York Times: “The Athenians were better than we are at enforcing accountability in their public officials. They had an examination to check the qualifications of an individual before entering office (a dokimasia ), but they also had a formal rendering of accounts at the end of a term of office ( euthynai ) and ostracism in the meantime."

Legislators were wined and dined at public expense using official drinking cups and tableware that one can see today in Athens.

Bribe-taking was not taken lightly in ancient Greece. In Laws Plato said that it merited “disgrace”. In Athens it was grounds for having one's citizenship revoked. Demosthenes was found guilty of accepting bribes in 324 B.C. and was fined 50 talens---which by some estimated is equal to $20 million in today's money---and ultimately got off with being exiled. Other officials were executed for taking bribes, University of Texas classic professor Michael Gagarin told the New York Times, “Bribery was taken very seriously and certainly could lead to capital punishment."

Tyrants and Ostracism in Ancient Greece

The first Greek "tyrants" were not tyrants as we think of them today. They were rulers who ousted local oligarchies with the support of the people. On one level they raised expectations of accountability but on other they were often corrupted by power and evolved in despots, who themselves were overthrown with the support of the people.

Politicians who fell out of favor could be ostracized---exiled for 10 years---by a vote of the assembled citizens, who cast their ballots by scratching the name of the ostracized person on a shard of pottery, or ostrakon (source of the word ostracize) used as ballots. The measure was set up not to punishment in any harsh or cruel way; the idea was simply to remove them from the political arena and public life. Many prominent Athenian politicians were ostracized.

Ostracism was introduced by Cleisthenes in 508 B.C. after exiling the tyrant Hippias, reportedly with the aim of preventing the emergence of a dictator who might seize powerful unlawfully by whipping up public discontent. It was used from 487 to 417 B.C., which some historians have pointed out was when Athens was at its peak, According to the procedure, citizens of ancient Athens were instructed to gather once a year and asked if they knew of anyone aiming to be a tyrant. If a simple majority voted yes the members were dispersed and told to come back in two months time and used an ostrakon to scratch the name of the citizen whom they deemed most likely to become a tyrant. The person who received the most votes in excess of a set number was expelled from the city-state for 10 years. This simple act is regarded by some historians as the foundation of democracy in ancient Athens.

Pottery shards that were used for secret votes have been found by archaeologists. Among the names that have been found on ostrakons are Pericles, Aristides and Thucydides. Pericles was nearly ostracized over opposition to his plan to build the Parthenon. A pile of 190 shards with the name Themosticles written on them by 12 individuals found in a well and is believed to be one of the first examples of vote rigging.

There were abuses of the system, notibly when strong politicians wanted to oust rivals. Pericles used the system to get rid of his main challenger, Thucydides. Ostracism itself was dropped when the powerful politicians Alcibiades and Nikias ganged to on Hyperbolos, a rival to both of them, and had him exiled.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Most of the information about Greco-Roman science, geography, medicine, time, sculpture and drama was taken from "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. Most of the information about Greek everyday life was taken from a book entitled "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.