HISTORY; SLAVERY IN NIGERIA

Portuguese adventurers who sailed southeast along the Gulf of Guinea in 1472 landed on the

coast of what became Nigeria. Others followed. They found people of varying cultures. Some

lived in towns ruled by kings with nobility and courtiers, very much like the medieval

societies they left behind them. More than a century earlier Benin exchanged ambassadors

with Portugal. But not all African societies were as developed. Some enjoyed village

existence in primeval forests remote from outside influences.

The first African slaves landed in the Portugese port of Lagos in 1442. The old slave market

now serves as an art gallery.

Economics was the driving force

From the outset, relations between Europe and Africa were economic. Portuguese merchants

traded with Nigerians from trading posts they set up along the coast. They exchanged items

like brass and copper bracelets for such products as pepper, cloth, beads and slaves - all

part of an existing internal Nigerian trade. Domestic slavery was common in Nigeria and well

before European slave buyers arrived, there was trading in humans. Black slaves were

captured or bought by Arabs and exported across the Saharan desert to the Mediterranean

and Near East.

In 1492, the Spaniard Christopher Columbus discovered for Europe a 'New World'. The find

proved disastrous not only for the 'discovered' people but also for Africans. It marked the

beginning of a triangular trade between Africa, Europe and the New World. European slave

ships, mainly British and French, took people from Africa to the New World. They were

initially taken to the West Indies to supplement local Indians decimated by the Spanish

Conquistadors. The slave trade grew from a trickle to a flood, particularly from the

seventeenth century onwards.

Portugal's monopoly in the obnoxious trade was broken in the sixteenth century when

England followed by France and other European nations entered the trade. The English led in

the business of transporting young Africans from their homeland to work in mines and till

lands in the Americas.

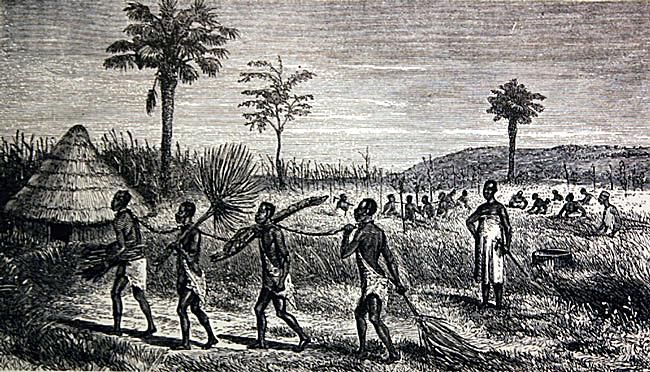

Most slaves sold by Nigerians

At the initial stage of the trade parties of Europeans captured Nigerians in raids on

communities in the coastal areas. But this soon gave way to buying slaves from Nigerian

rulers and traders. The vast majority of slaves taken out of Nigeria were sold by Nigerian

rulers, traders and a military aristocracy who all grew wealthy from the business. Most

slaves were acquired through wars or by kidnapping. " Olaudah Equiano, an ex-slave,

described in his memoirs published in 1789 how African rulers carried out raids to capture

slaves. "When a trader wants slaves, he applies to a chief for them, and tempts him with his

wares. It is not extraordinary, if on this occasion he yields to the temptation with as little

firmness, and accepts the price of his fellow creature's liberty with as little reluctance, as the

enlightened merchant. Accordingly, he falls upon his neighbours, and a desperate battle

ensues...if he prevails, and takes prisoners, he gratifies his avarice by selling them."

A profitable trade

European slave buyers made the greater profit from the despicable trade, but their Nigerian

partners also prospered. Many grew strong and fat on profits made from selling their

brethren. Tinubu square, commercial centre of today's Lagos and home to Nigeria's Central

Bank, is named after a major nineteenth century slave trader. Madam Tinubu was born in

Egbaland and rose from rags to riches by trading in slaves , salt and tobacco in Badagry.

She later became one of Nigeria's pioneering nationalists.

Nigeria's rulers, traders and military aristocracy protected their interest in the slave trade.

They discouraged Europeans from leaving the coastal areas to venture into the interior of the

continent. European trading companies realised the benefit of dealing with Nigerian suppliers

and not unnecessarily antagonising them. The companies could not have mustered the

resources it would have taken to directly capture the tens of millions of people shipped out

of Africa. It was far more sensible and safer to give Africans guns to fight the many wars

that yielded captives for the trade. The slave trading network stretched deep into the Africa's

interior. Slave trading firms were aware of their dependency on African suppliers. The Royal

African Company, for instance, instructed its agents on the West coast "if any differences

happen, to endeavour an amicable accommodation rather than use force." They were "to

endeavour to live in all friendship with them" and "to hold frequent palavers with the Kings

and the Great Men of the Country, and keep up a good correspondent with them, ingratiating

yourself by such prudent methods" as may be deemed appropriate.

Nigerians faced with a new world

Contact with Europe opened new images of the world for the Nigerian elite and presented

them with products of a civilisation which as the centuries passed became more

technologically differentiated from their own. The slave trade whetted their appetite for the

products of a changing world. Sadly it was not only tinpot rulers who were mesmerised by

the glitters of western artefacts.

European traders saw the advantages of helping Nigerian kings and chiefs realise their desire

to acquire western culture, if not for themselves then for their children. Hugh Crow, who

commanded the last British slave ship to leave a British port, wrote "It has always been the

practice of merchants and commanders of ships to Africa, to encourage the natives to send

their children to England as it not only conciliates their friendship, and softens their manner,

but adds greatly to the security of the traders." With their children in Europe,

African chiefs

were likely to be more accommodating, knowing full well their offspring could be held as

ransom.

African traders resist abolition of obnoxious trade

When Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807 it not only had to contend with opposition

from white slavers but also from Nigerian rulers who had become accustomed to wealth

gained from selling slaves or from taxes collected on slaves passed through their domain.

Nigerian slave-trading classes were greatly distressed by the news that legislators sitting in

parliament in London had decided to end their source of livelihood. But for as long as there

was demand from the Americas for slaves, the lucrative business continued.

The slave trade business continued in many parts of Africa for many decades after the British

abolished it. For as long as there was demand for slave labour in the Americas, the supply

was available. The British set up a naval blockade to stop ships carrying slaves from West

Africa, but it was not very effective in suppressing the trade. Thousands of slave ships were

detained during the decades the blockade was in operation. One Lieutenant Patrick Forbes, a

British naval officer, estimated in 1849 that during a period of 26 years 103,000 slaves were

emancipated by the warships of the naval blockade while ships carrying 1,795,000 slaves

managed to slip past the blockage and land their cargo in the Americas.

British efforts to suppress the trade made it even more profitable because the price of

slaves rose in the Americas. The numerous wars that plagued Yorubaland for half a century

following the fall of the Oyo empire was largely driven by demand for slaves. Reverend

Samuel Johnson wrote of the subjugation of neighbouring Yoruba kingdoms by Ibadan war-

chiefs in the 1850s: "Slave-raiding now became a trade to many who would get rich

speedily." It took the intervention of British colonialism to impose peace in Yorubaland in

- Slave trading for export ended in Nigeria and elsewhere in West Africa after slavery

ended in the Spanish colonies of Brazil and Cuba in 1880. A consequence of the ending of

the slave trade was the expansion of domestic slavery as Nigerian businessmen replaced

trade in human chattel with increased export of primary commodities. Labour was needed to

cultivate the new source of wealth for the Nigerian elites.

Abolition of the Slave Trade

In 1807 the Houses of Parliament in London enacted legislation prohibiting British subjects

from participating in the slave trade. Indirectly, this legislation was one of the reasons for

the collapse of Oyo. Britain withdrew from the slave trade while it was the major transporter

of slaves to the Americas.

Between them, the French and the British had purchased a majority of the slaves sold from

the ports of Oyo. The commercial uncertainty that followed the disappearance of the major

purchasers of slaves unsettled the economy of Oyo. Ironically, the political troubles in Oyo

came to a head after 1817, when the transatlantic market for slaves once again boomed.

Rather than supplying slaves from other areas, however, Oyo itself became the source of

slaves.

British legislation forbade ships under British registry to engage in the slave trade, but the

restriction was applied generally to all flags and was intended to shut down all traffic in

slaves coming out of West African ports. Other countries more or less hesitantly followed the

British lead. The United States, for example, also prohibited the slave trade in 1807

(Denmark actually was the first country to declare the trade illegal in 1792).

The Royal Navy maintained a prevention squadron to blockade the coast, and a permanent

station was established at the Spanish colony of Fernando Po, off the Nigerian coast, with

responsibility for patrolling the West African coast. Slaves rescued at sea were usually taken

to Sierra Leone, where they were released. Apprehended slave runners were tried by naval

courts and were liable to capital punishment if found guilty.

Still, a lively slave trade to the Americas continued into the 1860s. The demands of Cuba

and Brazil were met by a flood of captives taken in wars among the Yoruba and shipped

from Lagos, while the Aro continued to supply the delta ports with slave exportPortuguese adventurers who sailed southeast along the Gulf of Guinea in 1472 landed on the

coast of what became Nigeria. Others followed. They found people of varying cultures.

Some lived in towns ruled by kings with nobility and courtiers, very much like the medieval

societies they left behind them. More than a century earlier Benin exchanged ambassadors

with Portugal. But not all African societies were as developed. Some enjoyed village

existence in primeval forests remote from outside influences.

The first African slaves landed in the Portugese port of Lagos in 1442. The old slave market

now serves as an art gallery.

Economics was the driving force

From the outset, relations between Europe and Africa were economic. Portuguese merchants

traded with Nigerians from trading posts they set up along the coast. They exchanged items

like brass and copper bracelets for such products as pepper, cloth, beads and slaves - all

part of an existing internal Nigerian trade. Domestic slavery was common in Nigeria and well

before European slave buyers arrived, there was trading in humans. Black slaves were

captured or bought by Arabs and exported across the Saharan desert to the Mediterranean

and Near East.

In 1492, the Spaniard Christopher Columbus discovered for Europe a 'New World'. The find

proved disastrous not only for the 'discovered' people but also for Africans. It marked the

beginning of a triangular trade between Africa, Europe and the New World. European slave

ships, mainly British and French, took people from Africa to the New World. They were

initially taken to the West Indies to supplement local Indians decimated by the Spanish

Conquistadors. The slave trade grew from a trickle to a flood, particularly from the

seventeenth century onwards.

Portugal's monopoly in the obnoxious trade was broken in the sixteenth century when

England followed by France and other European nations entered the trade. The English led in

the business of transporting young Africans from their homeland to work in mines and till

lands in the Americas.

Most slaves sold by Nigerians

At the initial stage of the trade parties of Europeans captured Nigerians in raids on

communities in the coastal areas. But this soon gave way to buying slaves from Nigerian

rulers and traders. The vast majority of slaves taken out of Nigeria were sold by Nigerian

rulers, traders and a military aristocracy who all grew wealthy from the business. Most

slaves were acquired through wars or by kidnapping. " Olaudah Equiano, an ex-slave,

described in his memoirs published in 1789 how African rulers carried out raids to capture

slaves. "When a trader wants slaves, he applies to a chief for them, and tempts him with his

wares. It is not extraordinary, if on this occasion he yields to the temptation with as little

firmness, and accepts the price of his fellow creature's liberty with as little reluctance, as the

enlightened merchant. Accordingly, he falls upon his neighbours, and a desperate battle

ensues...if he prevails, and takes prisoners, he gratifies his avarice by selling them."

A profitable trade

European slave buyers made the greater profit from the despicable trade, but their Nigerian

partners also prospered. Many grew strong and fat on profits made from selling their

brethren. Tinubu square, commercial centre of today's Lagos and home to Nigeria's Central

Bank, is named after a major nineteenth century slave trader. Madam Tinubu was born in

Egbaland and rose from rags to riches by trading in slaves , salt and tobacco in Badagry.

She later became one of Nigeria's pioneering nationalists.

Nigeria's rulers, traders and military aristocracy protected their interest in the slave trade.

They discouraged Europeans from leaving the coastal areas to venture into the interior of the

continent. European trading companies realised the benefit of dealing with Nigerian suppliers

and not unnecessarily antagonising them. The companies could not have mustered the

resources it would have taken to directly capture the tens of millions of people shipped out

of Africa. It was far more sensible and safer to give Africans guns to fight the many wars

that yielded captives for the trade. The slave trading network stretched deep into the Africa's

interior. Slave trading firms were aware of their dependency on African suppliers. The Royal

African Company, for instance, instructed its agents on the West coast "if any differences

happen, to endeavour an amicable accommodation rather than use force." They were "to

endeavour to live in all friendship with them" and "to hold frequent palavers with the Kings

and the Great Men of the Country, and keep up a good correspondent with them, ingratiating

yourself by such prudent methods" as may be deemed appropriate.

Nigerians faced with a new world

Contact with Europe opened new images of the world for the Nigerian elite and presented

them with products of a civilisation which as the centuries passed became more

technologically differentiated from their own. The slave trade whetted their appetite for the

products of a changing world. Sadly it was not only tinpot rulers who were mesmerised by

the glitters of western artefacts.

European traders saw the advantages of helping Nigerian kings and chiefs realise their desire

to acquire western culture, if not for themselves then for their children. Hugh Crow, who

commanded the last British slave ship to leave a British port, wrote "It has always been the

practice of merchants and commanders of ships to Africa, to encourage the natives to send

their children to England as it not only conciliates their friendship, and softens their manner,

but adds greatly to the security of the traders." With their children in Europe, African chiefs

were likely to be more accommodating, knowing full well their offspring could be held as

ransom.

African traders resist abolition of obnoxious trade

When Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807 it not only had to contend with opposition

from white slavers but also from Nigerian rulers who had become accustomed to wealth

gained from selling slaves or from taxes collected on slaves passed through their domain.

Nigerian slave-trading classes were greatly distressed by the news that legislators sitting in

parliament in London had decided to end their source of livelihood. But for as long as there

was demand from the Americas for slaves, the lucrative business continued.

The slave trade business continued in many parts of Africa for many decades after the British

abolished it. For as long as there was demand for slave labour in the Americas, the supply

was available. The British set up a naval blockade to stop ships carrying slaves from West

Africa, but it was not very effective in suppressing the trade. Thousands of slave ships were

detained during the decades the blockade was in operation. One Lieutenant Patrick Forbes, a

British naval officer, estimated in 1849 that during a period of 26 years 103,000 slaves were

emancipated by the warships of the naval blockade while ships carrying 1,795,000 slaves

managed to slip past the blockage and land their cargo in the Americas.

British efforts to suppress the trade made it even more profitable because the price of

slaves rose in the Americas. The numerous wars that plagued Yorubaland for half a century

following the fall of the Oyo empire was largely driven by demand for slaves. Reverend

Samuel Johnson wrote of the subjugation of neighbouring Yoruba kingdoms by Ibadan war-

chiefs in the 1850s: "Slave-raiding now became a trade to many who would get rich

speedily." It took the intervention of British colonialism to impose peace in Yorubaland in

- Slave trading for export ended in Nigeria and elsewhere in West Africa after slavery

ended in the Spanish colonies of Brazil and Cuba in 1880. A consequence of the ending of

the slave trade was the expansion of domestic slavery as Nigerian businessmen replaced

trade in human chattel with increased export of primary commodities. Labour was needed to

cultivate the new source of wealth for the Nigerian elites.

Abolition of the Slave Trade

In 1807 the Houses of Parliament in London enacted legislation prohibiting British subjects

from participating in the slave trade. Indirectly, this legislation was one of the reasons for

the collapse of Oyo. Britain withdrew from the slave trade while it was the major transporter

of slaves to the Americans.

NOTE: NO CRITICISM, IT'S JUST AN HISTORY

Part 2 loading. Upvote and comment

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.afbis.com/analysis/slave.htm

Congratulations @goodyboi! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board

Congratulations @goodyboi! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!