Rameses

Rameses or Avaris?

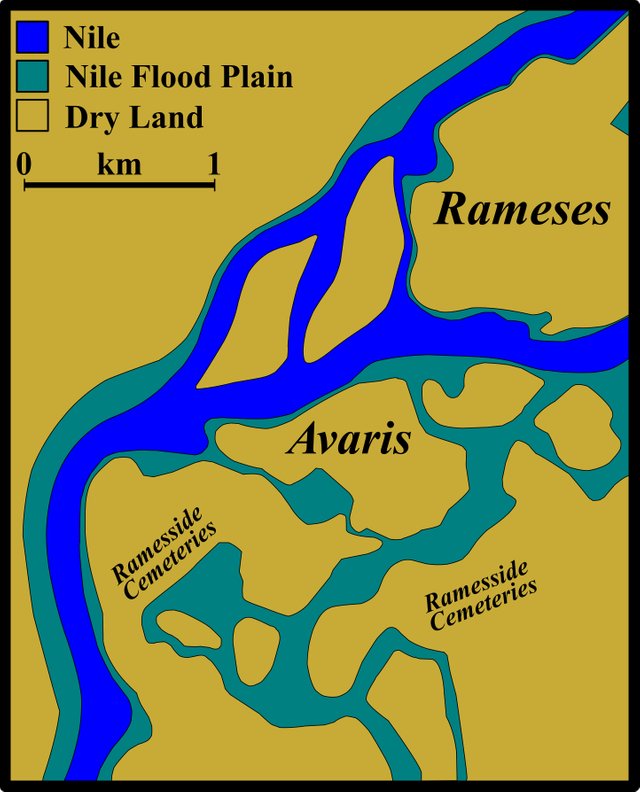

The first Station of the Exodus, Rameses, is generally identified with the ancient Egyptian city of Per-Ramesses, in the extreme eastern region of the Nile delta. This was built by Seti I (or, possibly, his father Ramesses I) of the 19th-Dynasty, but named for his son Ramesses II, who expanded it and made it his new capital. In the model of the Short Chronology that I am following, the Exodus occurred at the same time as the expulsion of the Hyksos (Assyrians) from Egypt—at the beginning of the 18th Dynasty. Ramesses II established Per-Ramesses about 150 years after the Exodus. So how could the Israelites have begun the Exodus at this city?

There is, in fact, a simple answer to this conundrum. Per-Ramesses was built on—or very close to—the site of the old city of Avaris, which had been the Hyksos’ capital, so the Biblical text is just using the modern name (Bietak & Forstner-Müller 23). There is nothing unusual in this. We still refer to the ancient Egyptian city of I͗wnw by its Greek name Heliopolis. This could mean that the record of the itinerary in Numbers 33 is not contemporary with the Exodus, but was compiled in Canaan (or perhaps Babylonia) at a much later date. It could also mean, of course, that the Short Chronology is simply wrong and that the Exodus took place some time after the foundation of Per-Ramesses, as many scholars believe.

Francis H Underwood, the editor of Karl Heinrich Brugsch’s writings on the Exodus, made the following pertinent remark:

Observe that Rameses has already been mentioned by anticipation, to mark the locality in which the children of Israel were settled when they came into Egypt: — Genesis 47:11: “And Joseph placed his father and his brethren, and gave them a possession in the land of Egypt, in the best of the land, in the land of Rameses, as Pharaoh had commanded.” (Brugsch 202)

To my knowledge, no one has deduced from this passage of Scripture that the Sojourn in Egypt must have begun during the 19th Dynasty.

The Way of Horus

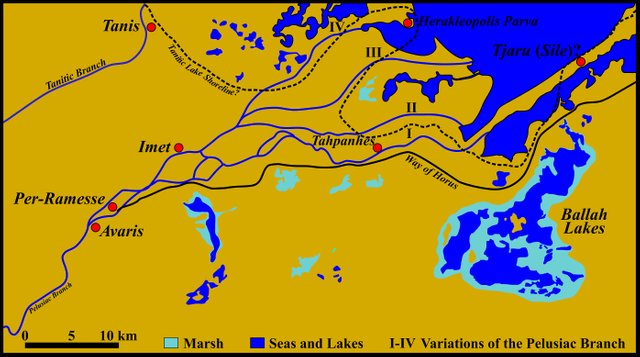

The city of Avaris stood at the western end of the Way of Horus, the principal road between ancient Egypt and southern Palestine:

Located east of the easternmost Nile branch, ‘the Waters of ReꜤ’, a navigable river channel flowing into the Mediterranean, the site of the later Per-Ramesses was situated at the beginning of the land route along the northern Sinai to Palestine. (Bietak & Forstner-Müller 23-24)

If the House of Israel wished to return to Canaan, and they were setting out from the vicinity of Avaris, it is only natural that they should have followed the Way of Horus. An army on the march could traverse this distance in under two weeks (Berlin & Brettler 133). How, then, did the Israelites end up in the Sinai Desert? This anomaly seems to have occurred to the compilers of the Book of Exodus, who included the following passage in their account of the Exodus:

And it came to pass, when Pharaoh had let the people go, that God led them not through the way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near; for God said, Lest peradventure the people repent when they see war, and they return to Egypt. But God led the people about, through the way of the wilderness of the Red sea: and the children of Israel went up harnessed out of the land of Egypt. (Exodus 13:17-18)

The way of the land of the Philistines refers to the Way of Horus. Elsewhere in the Old Testament, there are references to another road between Canaan and Egypt: the Way of Shur:

Now Sarai Abram’s wife bore him no children, and she had a maid an Egyptian, Hagar by name. And Sarai said unto Abram, Behold now, the Lord hath restrained me from childbearing, I pray thee go in unto my maid: it may be that I shall receive a child by her. And Abram obeyed the voice of Sarai. Then Sarai Abram’s wife took Hagar her maid the Egyptian, after Abram had dwelled ten years in the land of Canaan, and gave her to her husband Abram for his wife. And he went in unto Hagar, and she conceived: and when she saw that she had conceived, her dame was despised in her eyes. Then Sarai said to Abram, Thou doest me wrong, I have given my maid into thy bosom, and she seeth that she hath conceived, and I am despised in her eyes: the Lord judge between me and thee. Then Abram said to Sarai, Behold, thy maid is in thine hand: do with her as it pleaseth thee. Then Sarai dealt roughly with her: wherefore she fled from her. But the Angel of the Lord found her beside a fountain in the way of Shur. (Genesis 16:1-7)

There is still no scholarly consensus as to the identity of the Way of Shur. The Hebrew word Shur is believed to refer to a line of fortifications which the ancient Egyptians maintained to the east of the Nile Delta. In the 19th century, however, Heinrich Karl Brugsch was satisfied that he had solved the mystery:

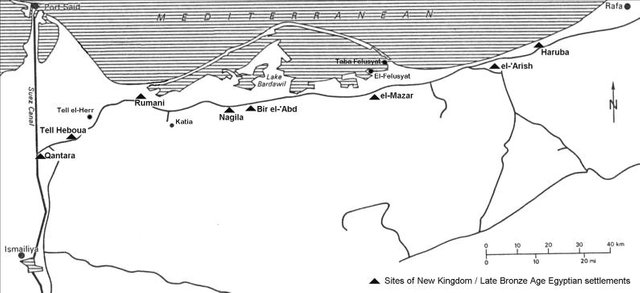

There lay in the direction of the north-east, on the western border of the so-called Lake Sirbonis, an important place for the defence of the frontier, called Anbu, that is ‘the wall,’ ‘the circumvallation.’ It is frequently mentioned by the ancients, not under its Egyptian appellation, but in the form of a translation. The Hebrews call it Shur, that is ‘the wall,’ and the Greeks ‘to Gerrhon,’ or ‘ta Gerrha,’ which means ‘the fences,’ or ‘enclosures.’ This remark will at a stroke remove all difficulties which have hitherto existed with reference to the origin of this word, which in spite of difference in sound nevertheless refers to one and the same place. (Brugsch 73-74)

Lake Sirbonis is generally identified with the modern Lake Bardawil, a salty lagoon on the northern shore of the Sinai Peninsula. If Brugsch is correct, then it appears that the way of Shur was just another Biblical name for the Way of Horus, the coastal road between Egypt and Canaan, and not a caravan route through the desert, as others have suggested.

Whoever travelled eastwards from Egypt to leave the country, was obliged to pass the place called ‘the walls,’ before he was allowed to enter the road of the Philistines, as it is called in Holy Writ, on his further journey. An Egyptian garrison, under the command of a captain, guarded the passage through the fortress, which only opened and closed on the suspicious wanderer if he was furnished with a permission from the royal authorities. Anbu-Shur-Gerrhon was also the first stopping-place on the great military road, which led from the Delta by Chetam-Etham and Migdol to the desert of Shur. (Brugsch 74)

So, did the Israelites initially set out along the Way of Horus before turning aside? On this point the Book of Exodus is quite explicit:

But God led the people about. (Exodus 13:18a)

In Young’s Literal Translation, this half-verse is rendered:

[A]nd God turneth round the people the way of the wilderness of the Red Sea ... (Exodus 13:18)

In other words, the House of Israel did indeed set out from the land of Rameses along the Way of Horus—as one would expect them to have done—but then, for one reason or another, they turned off this road and headed south or south-east away from the coast.

Legends of the Jews

In the early 20th century, Louis Ginzberg recorded the following legend, which purports to explain why the Israelites did not return to Canaan by the shortest road:

For several reasons God did not permit the Israelites to travel along the straight route to the promised land. He desired them to go to Sinai first and take the law upon themselves there, and, besides, the time divinely appointed for the occupation of the land by the Gentiles had not yet elapsed. Over and above all this, the long sojourn in the wilderness was fraught with profit for the Israelites, spiritually and materially. If they had reached Palestine directly after leaving Egypt, they would have devoted themselves entirely each to the cultivation of his allotted parcel of ground, and no time would have been left for the study of the Torah. In the wilderness they were relieved of the necessity of providing for their daily wants, and they could give all their efforts to acquiring the law. On the whole, it would not have been advantageous to proceed at once to the Holy Land and take possession thereof, for when the Canaanites heard that the Israelites were making for Palestine, they burnt the crops, felled the trees, destroyed the buildings, and choked the water springs, all in order to render the land uninhabitable. Hereupon God spake, and said: “I did not promise their fathers to give a devastated land unto their seed, but a land full of all good things. I will lead them about in the wilderness for forty years, and meanwhile the Canaanites will have time to repair the damage they have done.” Moreover, the many miracles performed for the Israelites during the journey through the wilderness had made their terror to fall upon the other nations, and their hearts melted, and there remained no more spirit in any man. They did not venture to attack the Israelites, and the conquest of the land was all the easier.

Nor does this exhaust the list of reasons for preferring the longer route through the desert. Abraham had sworn a solemn oath to live at peace with the Philistines during a certain period, and the end of the term had not yet arrived. Besides, there was the fear that the sight of the land of the Philistines would awaken sad recollections in the Israelites, and drive them back into Egypt speedily, for once upon a time it had been the scene of a bitter disappointment to them. They had spent one hundred and eighty years in Egypt, in peace and prosperity, not in the least molested by the people. Suddenly Ganon came, a descendant of Joseph, of the tribe of Ephraim, and he spake, “The Lord hath appeared unto me, and He bade me lead you forth out of Egypt.” The Ephraimites were the only ones to heed his words. Proud of their royal lineage as direct descendants of Joseph, and confident of their valor in war, for they were great heroes, they left the land and betook themselves to Palestine. They carried only weapons and gold and silver. They had taken no provisions, because they expected to buy food and drink on the way or capture them by force if the owners would not part with them for money.

After a day’s march they found themselves in the neighborhood of Gath, at the place where the shepherds employed by the residents of the city gathered with the flocks. The Ephraimites asked them to sell them some sheep, which they expected to slaughter in order to satisfy their hunger with them, but the shepherds refused to have business dealings with them, saying, “Are the sheep ours, or does the cattle belong to us, that we could part with them for money?” Seeing that they could not gain their point by kindness, the Ephraimites used force. The outcries of the shepherds brought the people of Gath to their aid. A violent encounter, lasting a whole day, took place between the Israelites and the Philistines. The people of Gath realized that alone they would not be able to offer successful resistance to the Ephraimites, and they summoned the people of the other Philistine cities to join them. The following day an army of forty thousand stood ready to oppose the Ephraimites. Reduced in strength, as they were, by their three days’ fast, they were exterminated root and branch. Only ten of them escaped with their bare life, and returned to Egypt, to bring Ephraim word of the disaster that had overtaken his posterity, and he mourned many days.

This abortive attempt of the Ephraimites to leave Egypt was the first occasion for oppressing Israel. Thereafter the Egyptians exercised force and vigilance to keep them in their land. As for the disaster of the Ephraimites, it was well-merited punishment, because they had paid no heed, to the wish of their father Joseph, who had adjured his descendants solemnly on his deathbed not to think of quitting the land until the true redeemer should appear. Their death was followed by disgrace, for their bodies lay unburied for many years on the battlefield near Gath, and the purpose of God in directing the Israelites to choose the longer route from Egypt to Canaan, was to spare them the sight of those dishonored corpses. Their courage might have deserted them, and out of apprehension of sharing the fate of their brethren they might have hastened back to the land of slavery. (Ginzberg 6-9)

None of this is particularly convincing, though the tradition of the Ephraimites returning to Canaan before the Exodus is an interesting one—even if it did take them only one day to cover the distance from Egypt to Gath.

One thing is clear, however: the question of why the Israelites did not return to Canaan by the shortest route is one that has exercised the minds of Biblical scholars for over two thousand years.

To be continued ...

References

- Adele Berlin & Marc Zvi Brettler (editors), _The Jewish Study Bible , Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

- Manfred Bietak & Irene Forstner-Müller, The Topography of New Kingdom Avaris and Per-Ramesses, in M Collier & S Snape (editors), Ramesside Studies in Honour of K. A. Kitchen, pp 23-51, Rutherford Press, Bolton (2011)

- Heinrich Karl Brugsch, The True Story of the Exodus of Israel, Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Francis H Underwood, Lee and Shepard Publishers, Boston (1880)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 3, Translated from the German by Paul Radin, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1911)

Image Credits

- Avaris and Rameses: Adapted from Bietak & Forstner-Müller, The Topography of New Kingdom Avaris and Per-Ramesses, p 22, Figure 25, Fair Use

- The Way of Horus: Adapted from Figure 1: Historical Landscape of the Northeastern Nile Delta, © Bietak & Forstner-Müller, Fair Use

- Hagar in the Wilderness: Wikimedia Commons, Giovanni Lanfranco (artist), Louvre Museum, Public Domain

- Lake Sirbonis and the Way of Horus: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Tell el-Habua: A Frontier Fortress on the Way of Horus: © 2018 Biblical Archaeology Society, Fair Use

- Louis Ginzberg: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

Resteemed and Upvote

wow very informative article about rameses with beautiful images

Excellent post nice history really amazing i like your post thanks for share dear @harlotscurse

Excellent post good article very beautiful history i like your post thanks for share dear @harlotscurse

Religious and historical post is always awsome. I like them always. I am also a history subject student

Very good post dear bro... love you

Posted using Partiko iOS