History of Japan | The position of a woman in Japanese society XVII

Kind time of the day, dear friends!

In the 17th and 19th centuries, most samurai ideologists and authors of home codes, which I spoke about in one of the previous posts , were written exclusively with the expectation of a male audience , for the family economy was transmitted through the male line. In addition, all important public positions were also occupied by men . In the book "Khakagure", authored by the samurai Yamamoto Tsunetomo, it is explicitly stated: "Daughters stain the name of the family and are a disgrace to the parents. The exception is the eldest daughter, and the rest can be neglected . "

Despite such a very categorical and rude attitude on the part of Yamamoto, other authors pay more attention to women, namely, the role that they expect from a woman in their home. One of the most popular treatises on the education of women was the work "Great Teaching for Women," which in 1716 was published by the Confucian scholar Kaibara Ecken .

Kaibara Ecken. Bronze statue in the philosopher Fukuoka's hometown *

In 19 chapters, he argued that a woman in all must obey his man and all his life should play the role of a diligent housewife. As for youth, "the main duty of the girl in the parents' home is to show respect for their father and mother . " After the marriage, the woman was supposed to "look at her husband as her master and serve him with all courtesy" and in no case do not contradict him, fulfilling all the orders of her husband. The birth of children, preferably boys, was one of the main duties of the wife.

With the advent of the offspring, among other things, the mother must "feed, wash, sew clothes," and so on and so forth. In addition, the wife had to honor her husband's parents at times stronger than her own, and fulfill any of their demands. Where does a woman have to take so much time and energy for all this, Kaibara Ecken does not specify.

As for the girls who neglect all of the above and live "not according to the rules," they are miserable according to Ecken's teaching and are weak, because they succumbed to their female "inherent flaws" - slander, envy, stupidity and anger. Such girls, according to Ecken, once again prove the superiority of men over women and destroy marriage by their behavior. Therefore, the "Great Teaching for Women" gives any man the right to divorce his wife in the following cases: if she does not obey his parents, if she can not give birth to a child, if she was convicted of treason, if she is excessively jealous , if she is ill with a severe Illness and if it destroys harmony in the house. Points relating to jealousy and harmony in the house, Struck me the most. Such are the conditions ...

I must say that such ideas at that time were inherent not only to Kaibara Ecken. For example, the famous Japanese scientist of the 18th century, Hosoy Heisu constantly repeated: "In her youth, the girl must obey her parents. Having married, she must obey her husband. In old age, she must obey her sons . " In principle, all such sayings can be reduced to exactly two words: "Must obey!".

Women, whether peasant women or girls of noble families, were regarded by the Japanese of that era as a kind of homogeneous mass , which must necessarily be guided and instructed on the true path. Their "clenched hearts", unlike open males, easily make them evil and vain, greedy and deceitful . Therefore, every girl through obedience, purity, benevolence, thrift, modesty and zeal must suppress her "inner" and find a true heart.

It must be admitted that such sermons were quite effective - the generations of samurai daughters, merchants and peasants became obedient wives , as they were represented in their works by Kaibara Ecken and others. However, although many of the commandments of Japanese thinkers and in truth have firmly settled in Japanese social thought of that era, more often than not idealized codes of conduct were quite different from real life. All this theory was very slender and beautiful, but in life everything was a little different.

The first thing I would like to note: Japanese women were not so strongly attached to the household. For example, urban women often equals (!) Helped their husbands to trade and were even accounts of income and expenditure. Moreover, in many cities in the west of Japan, a woman could become the head of a whole household, although usually this function is performed solely by a man! In the provinces the same picture: the wife and her husband together were farming and working in the fields.

Japanese peasants in the 19th century. Photo in color. *

Women who were not happy in marriage, tried to find a way to survive in adverse conditions. Some continued to live with their hated husbands and tried to stop their lives in hell . Others simply refused husbands sexual pleasure. The woman was not entitled to divorce , so she had to act in such ways. As for the divorce, the warrior who wants to break the marriage relationship, simply wrote to his wife a letter called "three and a half lines." Following this letter, the woman received her dowry back and returned to her parents, while the children remained behind their father. Repeated marriages were unacceptable, since this was considered a great disgrace.

As for women from the peasant and trade classes, they had more freedom. Some of them went to the so-called "divorce temples" to stop unwanted marriage. In these temples, the woman served for 2 years, after which she became absolutely free . However, it was a long and thorny path, so most of the peasants and townsfolk simply left the house , often taking with them children and money. Moreover, "divorced" in this way women often married again, and this did not stain their honor and dignity, as it was with the girls of the highest circles.

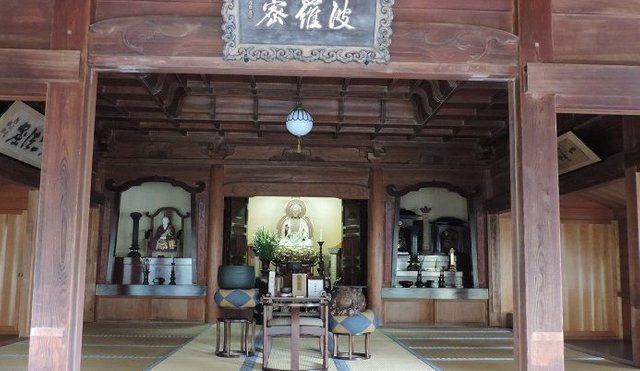

Tokaeji Temple of Divorce in Kamakura. It was founded in 1285. *

To the conversation about the lowly women, many of them before marriage generally worked outside the house! They went to work as seamstresses, laundresses, bath attendants, prostitutes, nuns, servants, masseuses, saleswomen and even carpenters. Most of the women went to earn money as maids in the homes of wealthy merchants and noble samurai. Besides, women were far from always distinguished by the obedience and obedience that the authors of numerous tracts wanted to see in them. For example, maid servants who lived outside their home used bad reputation because they constantly dismissed all kinds of false gossip about their patrons and actively discussed with each other their family problems. Also, they often steal from home owners, And sometimes directly attacked their employers. For example, in the 1660s, one woman alternately worked in six (!) Samurai houses, each of which she stealthily steal, then burned the house to ashes! In the end, she was seized and cooked a cauldron with boiling water =)

Tintyo. Beauty Kokonoe from the house of Nishidaeus with maidens. Engraving. *

Thus, the examples of "ideal behavior" described in the treatises, just like the set of instructions for young girls, did not reflect the real state of affairs . All these were just beautiful words, the desired one, which did not dovetail with reality. Of course, most of the young Japanese women of the 17th-19th centuries and in truth adhered to all the rules described in the codes - this is a fact, but these instructions were never binding on the "true way", and therefore many girls (especially the ignorant) they boldly neglected And quite comfortable feeling!

Hi. I am a volunteer bot for @resteembot that upvoted you.

Your post was chosen at random, as part of the advertisment campaign for @resteembot.

@resteembot is meant to help minnows get noticed by re-steeming their posts

To use the bot, one must follow it for at least 3 hours, and then make a transaction where the memo is the url of the post.

If you want to learn more - read the introduction post of @resteembot.

If you want help spread the word - read the advertisment program post.

Steem ON!