The Story of Money 4: Markets, Metals, Coins, and Military

Τί δέ τις; Τί δ' οὔ τις; Σκιᾶς ὄναρ ἄνθρωπος. — Πίνδαρος

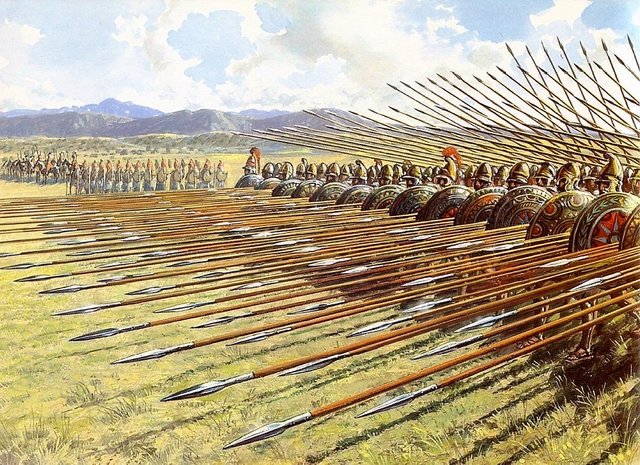

The sarissa’s song is sad song, He pipes it soft and low. I’d ply a gentler trade says he, but war is all I know

In this series we've been taking a look at the history of money. Strangely enough, much of this actual history is rather uncommon knowledge. It's been written down, for those who care to look...but for the most part, the stories that get told in our world about how money came to be are extremely basic...

Before there was money, everyone had to barter for what they needed to survive...

And not at all historically accurate. (Read up on my previous post, the Myth of Barter if you haven't yet!)

The Myth of Barter

Today we're going to look at the exact points in history where coinage began showing up. This is quite well documented, in part due to the severity in which they begin showing up in the archeological record after 600 bc in the Aegean, The Indus Valley, and Yellow River Valley(Modern Day Turkey, India, and China). We are going to be taking a look at the relationship between Markets, Military, Metal, Mining, Slavery, War, and Money during this time period. It may not be a very popular line of inquiry these days, but by all accounts, Markets themselves may have been an invention of the military.

Bronze Age

this is a REALLY VERY inadequate wide description of a HUGE span of time involving thousands upon thousands of very different people with all manner of inconceivably strange history and stories. To even begin doing justice to this time period, check out Europe Between The Oceans by Barry Cunliffe

In order to have a flea's sneeze of what being a human being in 600 bc was like in any of these three places we need a bit more context.

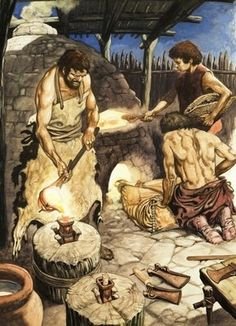

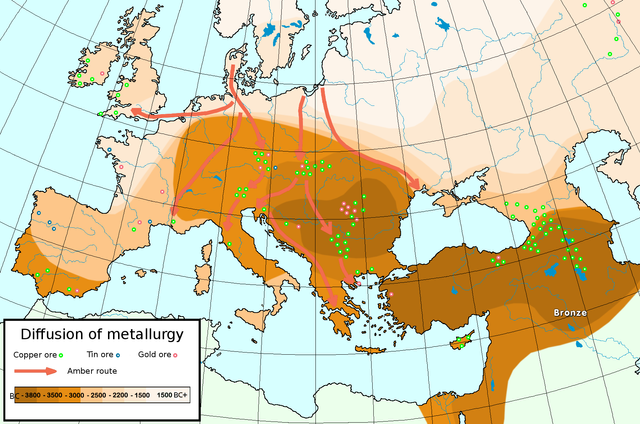

After untold aeons of time (hundreds of thousands of years) of rock, bone, wood, teeth, and sometimes small amounts of surface copper being primary materials available for hard tools, at some point some people starting mixing other materials into their copper, which by itself is quite soft and won't hold a edge. Somewhere between 3800-3300 BC, one of those materials happened to be tin, which is both rare and occurs naturally in concentration in very few places.

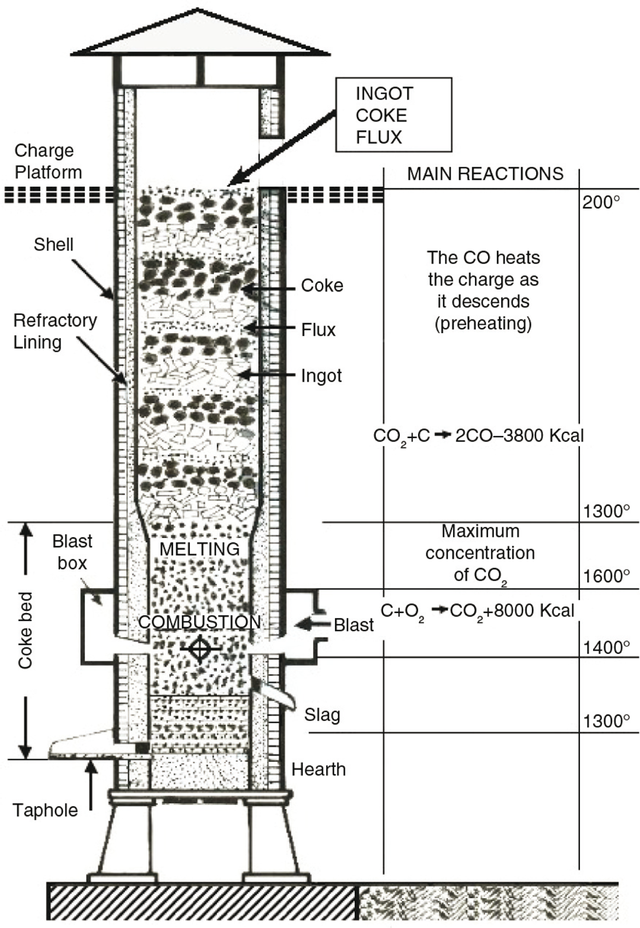

The result is a hard red alloy-metal we know today by the name bronze. In order to smelt Bronze, you need to be able to reach temperatures of 1000-1700 Fahrenheit, with the higher temperatures improving the durability of the finished product.

It's substantially harder then copper, but requires some basic metallurgy. Bronze working and basic smelting techniques began showing up in the archeological record around 3800 BC, and were the dominant form of metalworking in places which used such technology until around 1200 BC. This varied quite hugely from place to place, but in the earliest places centered around eastern europe, in what is now Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, and the other side of the Aegean in present day Turkey.

The power of bronze weapons, armor, and tools is hard to imagine. This was probably viewed in a near mystical fashion, the complexities of metallurgy slowly percolating into larger and larger geographic and cultural spheres. All manner of social elites raced to gain access to this new and powerful substance. Whole empires rose on the back of the tin trade. It takes relatively little tin and a lot of the much more common copper to make bronze. Extensive complex societies were established around the Aegean, The Balkans, and Northern Africa during this time, their power based on their ability to control the flow of Tin, and thus production of Bronze.

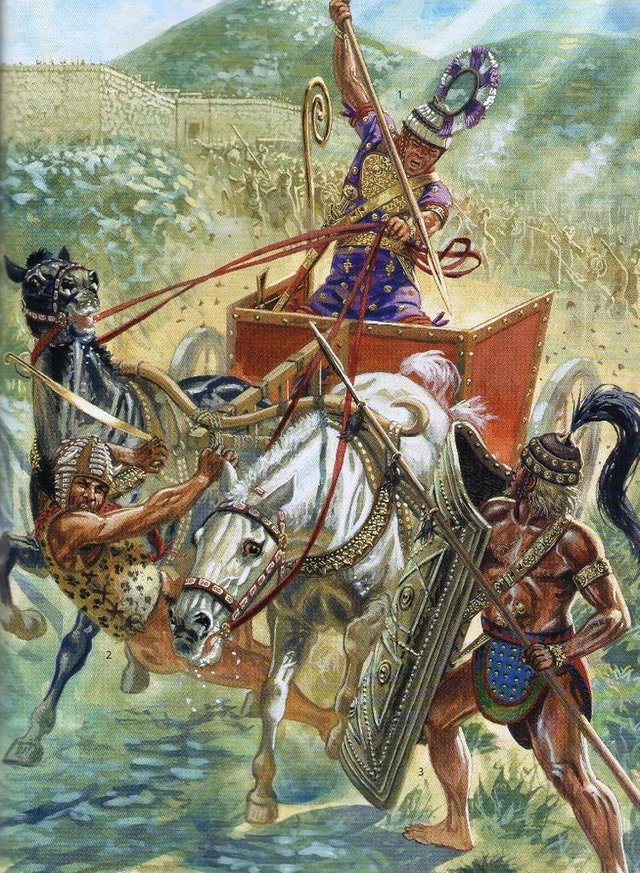

By all archeological records, these political-cultural-economic systems grew and persisted for TWO to THREE thousand years until around 1200 BC. So bronze had the monopoly on weaponry and tools, and the people who managed to keep themselves in the Tin trade had a monopoly on bronze. By the later years, huge civilizations were spread along the coastlines, utilizing intensive agriculture, extensive architecture, global trade routes, slavery, heavy specialization of labor, and lots of bronze.

The social hierarchy of these later bronze age civilizations was very stratified. Lots of wealth, power, and materials goods were concentrated in the hands of the few. War and fighting tended to be dominated by the landed aristocracy, who were able to put enough resources towards mounts and chariots which were extremely powerful war technology. This system of nobility was the primary power structure in many of these societies, and credit, accounting, and debt were core economic systems, even though coinage would take another 600 years to surface.

This time period also saw vast amounts of deforestation. An estimated 120 pine trees would be needed to make the requisite 6 tons of charcoal to produce a single oxhide ingot of bronze. These ingots were much larger than what we see today, think a heavy piece of sheet metal with four limbs so it could be easily carried by a group of people.

After thousands of years of ossified power structures, extreme social stratification, and rampant deforestation things crumbled into a complete maelstrom centered around the appearance of a new body of knowledge. This knowledge would undermine all existing power structures as it spread, and with it, old societies crumbled, and new cultures were forged in the chaos of mass warfare and regional hysteria.

This new knowledge was Iron, and is the fourth most common element in Earth's crust. Where Tin once determined who was in control of metal tools, weapons, and armor, now a whole realm of armaments and technological possibilities began to open up to any people with the know how and desired to take advantage of it. This period gets referred to as the Late Bronze Age Collapse around 1200 BC.

The thing about smelting iron is you need a LOT more heat than smelting bronze, and to effectively control the composition of the final product you're dealing with incredibly small differences, workable iron falls within the range of about 1.2% and 3% added carbon. When you account for differing compositions of local ore deposits, you can imagine the immense difficulty and importance in knowledge of metal working.

Working metal is in fact so complex, that in modern times, Western Europeans spent hundreds of years trying to recreate steel that was being made in India and the Middle east and was traded to Europe under a variety of names for thousands of years. It wasn't until the 1980's that a blacksmith and a PHD Metallurgist colluded for over ten years with the use of an electron microscope before they were able to reproduce Damascus Steel blades to the same level of quality of those collected from antiquity.

So you have all these old and large civilizations collapsing, and over the next 600 years the power structures slowly begin to reform into smaller groups of city states. Ironworking as a craft spread quickly throughout the mediterranean, and where metal weapons were once the domain of wealthy aristocrats, Iron is now a relatively cheap and accessible form of weaponry.

It's against this backdrop that coinage first shows up on the scene, in

the Lydian Kingdom of Sardis

in what would later be known as Persia, and now Turkey

These are some of those first Lydian coins, made of naturally occurring electrum. There are dozens of denominations from a whole gold stater, to a 1/2, a 1/3, a sixth, a twelfth, 1/24, 1/36, 1/48, 1/96....in fact it might also be were the term "rational thinking" originated, albeit in a different language, but eventually ending up in roman Latin. Rational almost certainly descends from Ratio, and this was the first time in history when everyday people were expected to start thinking in ratios, before that it would have been mostly the realm of those in architecture and mathematics.

While we will be tracking with the story of coinage around the Aegean, know that at almost identical times coinage also showed up in China and India, under very similar circumstances. Heres an excerpt from Debt: the first 5000 years

Gold, silver, and bronze— the materials from which coins were made— had long been the media of international trade; but until that time, only the rich had actually had much in their possession. A typical Sumerian farmer may well have never had occasion to hold a substantial piece of silver in his hand, except perhaps at his wedding. Most precious metals took the form of wealthy women’s anklets and heirloom chalices presented by kings to their retainers, or it was simply stockpiled in temples, in ingot form, as sureties for loans. Somehow, during the Axial Age (Graeber is referring to around 600bc to 300ad here), all this began to change. Large amounts of silver, gold, and copper were dethesaurized, as the economic historians like to say; it was removed from the temples and houses of the rich and placed in the hands of ordinary people, was broken into tinier pieces, and began to be used in everyday transactions.

How? Israeli Classicist David Schaps provides the most plausible explanation:

Soldiers who plunder(remember that prior to this the majority of armies were aristocratic empires, but after the late bronze age collapse, and the introduction of iron, we start to see a lot more everyday soldiers) may indeed go first for the women, the alcoholic drinks, or the food, but they will also be looking around for things of value that are easily portable. A long-term standing army will tend to accumulate many things that are valuable and portable— and the most valuable and portable items are precious metals and precious stones. It may well have been the protracted wars among the states of these areas that first produced a large population of people with precious metal in their possession and a need for everyday necessities … Where there are people who want to buy there will be people willing to sell, as innumerable tracts on black markets, drug dealing, and prostitution point out … The constant warfare of the archaic age of Greece was a powerful impetus for the development of market trade, and in particular for market trade based on the exchange of precious metal, usually in small amounts.

If plunder brought precious metal into the hands of the soldiers, the market will have spread it through the population. Now war and plunder were nothing new. The Homeric epics, for instance, show a well-nigh obsessive interest in the division of the spoils. But what the Axial Age also saw— again, equally in China, India, and the Aegean— was the rise of a new kind of army, made up not of aristocratic warriors and their retainers, but trained professionals. The period when the Greeks began to use coinage, for instance, was also the period when they developed their famous phalanx tactics, which required constant drill and training of the hoplite soldiers. The results were so extraordinarily effective that Greek mercenaries were soon being sought after from Egypt to Crimea. But unlike the Homeric retainers, who could simply be ignored, an army of trained mercenaries needs to be incentivized. One could perhaps provide them all with livestock, but livestock are hard to transport.

One of the most plausible theories is that the very first Lydian coins were invented explicitly to pay mercenaries. This might help explain why the Greeks, who supplied most of the mercenaries, so quickly became accustomed to the use of coins, and why the use of coinage spread like wildfire across the Hellenic world, so that by 480 bc(a hundred years after showing up in Lydia) there were hundreds of mints operating in different Greek cities, even though at that time, none of the great trading nations of the Mediterranean had as yet showed the slightest interest in them.

The Phoenicians, for example, were considered the greatest merchants and bankers of antiquity. They were also great inventors, having been the first to develop both the alphabet and the abacus.

Yet for centuries after the invention of coinage, they preferred to continue conducting business as they always had, with unwrought ingots and promissory notes. Phoenician cities struck no coins until 365 bc, and while Carthage, the great Phoenician colony in North Africa that came to dominate commerce in the Western Mediterranean, did so a bit earlier, it was only when “forced to do so to pay Sicilian mercenaries; and its issues were marked in Punic, ‘for the people of the camp.’ ”

On the other hand, in the extraordinary violence of the Axial Age, being a “great trading nation” (rather than, say, an aggressive military power like Persia, Athens, or Rome) was not, ultimately, a winning proposition. The fate of the Phoenician cities is instructive. Sidon, the wealthiest, was destroyed by the Persian emperor Artaxerxes III after a revolt in 351 bc. Forty thousand of its inhabitants are said to have committed mass suicide rather than surrender. Nineteen years later, Tyre was destroyed after a prolonged siege by Alexander: ten thousand died in battle, and the thirty thousand survivors were sold into slavery. Carthage lasted longer, but when Roman armies finally destroyed the city in 146 bc, hundreds of thousands of Carthaginians were said to have been raped and slaughtered, and fifty thousand captives put on the auction block, after which the city itself was razed and its fields sowed with salt. All this may bring home something of the level of violence amidst which Axial Age thought developed.

It would seem that the fiscal policies of many Greek cities amounted to little more then elaborate systems for the distribution of loot, few ancient cities if any, went so far as to outlaw debt peonage, instead they threw money at the problem. Gold, silver, and metals acquired in war, or mined by slaves pouring into the economic system thus creating the basis for a class of free farmers whose children would, in turn, be free to spend much of their time training for war. Coinage played a critical role in maintaining this kind of peasantry— secure in their landholding, not tied to any great lord by bonds of debt.

Mints were located in temples (the traditional place for depositing spoils), and city-states developed endless ways to distribute coins, not only to soldiers, sailors, and those producing arms or outfitting ships, but to the populace generally, as jury fees, fees for attending public assemblies, or sometimes just as outright distributions, as Athens did most famously when they discovered a new vein of silver in the mines at Laurium in 483 bc. At the same time, insisting that the same coins served as legal tender for all debts due to the state ensured that they would be in sufficient demand that markets would soon develop.

It was slavery, though, that makes all this possible.

As the figures concerning Sidon, Tyre, and Carthage suggest, enormous numbers of people were being enslaved in many of these conflicts, and, of course, many slaves ended up working in the mines, producing even more gold, silver, and copper. (The mines in Laurium reportedly employed ten to twenty thousand of them.) Geoffrey Ingham calls the resulting system a “military-coinage complex”— though I think it would be more accurate to call it a “military-coinage-slavery complex.”

Anyway, that describes how it worked in practice. When Alexander set out to conquer the Persian Empire, he borrowed much of the money with which to pay and provision his troops, and he minted his first coins, used to pay his creditors and continue to support the money, by melting down gold and silver plundered after his initial victories. However, an expeditionary force needed to be paid, and paid well: Alexander’s army, which numbered some 120,000 men, required half a ton of silver a day just for wages. For this reason, conquest meant that the existing Persian system of mines and mints had to be reorganized around providing for the invading army; and ancient mines, of course, were worked by slaves.

In turn, most slaves in mines were war captives. Presumably most of the unfortunate survivors of the siege of Tyre ended up working in such mines. One can see how this process might feed upon itself. Alexander was also the man responsible for destroying what remained of the ancient credit systems, since not only the Phoenicians but also the old Mesopotamian heartland had resisted the new coin economy. His armies not only destroyed Tyre; they also dethesaurized the gold and silver reserves of Babylonian and Persian temples, the security on which their credit systems were based, and insisted that all taxes to his new government be paid in his own money. The result was to “release the accumulated specie of century onto the market in a matter of months,” something like 180,000 talents, or in contemporary terms, an estimated $ 285 billion USD.

The Hellenistic successor kingdoms established by Alexander’s generals, from Greece to India, employed mercenaries rather than national armies, but the story of Rome is similar to that of Athens. Its early history, as recorded by official chroniclers like Livy, is one of continual struggles between patricians and plebians, and of continual crises over debt. Periodically, these would lead to what were called moments of “the secession of the plebs,” when the commoners of the city abandoned their fields and workshops, camped outside the city, and threatened mass defection. Here, too, the patricians were ultimately faced with a decision: they could use agricultural loans to gradually turn the plebian population into a class of bonded laborers on their estates, or they could accede to popular demands for debt protection, preserve a free peasantry, and employ the younger sons of free farm families as soldiers.

As the prolonged history of crises, secessions, and reforms makes clear, the choice was made grudgingly. The plebs practically had to force the senatorial class to take the imperial option.

One final note here. In Greece as in Rome, attempts to solve the debt crisis through military expansion were always just ways of fending off the problem— and they only worked for a while. When expansion stopped, the system breaks down.

"Anyone who believes in unlimited growth on a physically finite planet is either mad or an economist"

-Kenneth Boulding

Thankyou for your support and thoughts! I've taken a lot of material from Debt: The first 5000 years by David Graeber, I would highly recommend reading it!

The Story of Money

The Story of Money 1: Intro

The Story of Money 2: Work, Wage, and Labor

The Story of Money 3: The Myth of Barter

The Story of Money 4: Markets, Metals, Coins, and Military

I think what is silently implied here ( correct me if I'm wrong) is the notion of legal tender.

Legal tender as a notion inclues enforcement. Without enforcement legal tender has no meaning thus when someone ( an emperor as in the case of Alexander ) sets the medium of settlements/ exchange he also has to enforce that this remains as one.

As a matter of fact, this enforcement doesn't have to be imposed on the whole of society but only a small part of it in order to propagate and have full effect ( the army, mercs etc ). You pictured the situation really well and I think it's a pretty straightforward line of thinking. The relation between money and power is a very strange one and there are aspects of it that haven't been explored yet or even fully understood. Perhaps there are vested interests that are actively hindering this attempt, thus the confusion regarding the roots of money. Thinking of today, I think that the real problem of this money-power relation lies to the fact that we have before ourselves a vast armaments industry that serves no other purpose other than promoting their products. And it's not your average bronze age blacksmith that makes swords when asked to but huge entities with vast resources that are forward planning and set a steady supply of ever evolving armaments ( remember Eisenhower's warning ).Or a war breaks out I'd like to add..

Great article mate! Take care!

MhmmmM!!!!! Yeah. That is at the essence of it isn't it. So if legal tender is enforcing that your currency gets used for your own taxes, debts, etc...is there a different word for say, the way that the US dollar is 'strongly encouraged' to be used in global petroleum transactions, and when people have tried to use their own currencies for this, they either end up with some chilling trade sanctions, or perhaps a full own invasion.

What was Eisenhower's warning? I don't think I know it.

Yeah unfortunately, that seems to be the more common result.

Sorry for taking that long to answer back, I was away at work for over a week and just returned today!

I think it's from his farewell speech when he left the office of president. I recommend watching it all in case you haven't, he raises some pretty interesting and important issues and it's still very very relevant today ( i'd dare to say more than ever )..

You are right about the petro dollar, I pretty much believe that also. If we also consider the overlapping interests between big oil and big arms we can get the whole picture. Just look at Saudi Arabia. They have an abyssmal human rights track record, they are most probably funding extremists and poison minds through their salafi / wahhabi indoctrination but they are considered a ''close'' ally of the US. Doesn't make much sense to me! When you add the $ in the equation though suddenly it does make ''sense''!

Wow this was a really detailed account of the military operations driving the economy of the times. It was interesting how the Bronze and then later Iron smelting technology was used to support the war efforts. Also interesting how the precious metal coinage was used to fund the mercenaries, which created the whole Military-Coinage-Slavery-Complex. The whole economy centered around this process.

Its kind of interesting how throughout the ages so little has changed. Mainly just the technology changes, yet not mankind.

Pretty wild huh...I sort of wonder if crypto-currency might end up having a similar effect on the world as did Iron, in causing massive upheaval against the old system, but ultimately just putting different players in the same old game.

Yes, I agree crypto-currency could cause that to happen. I am seeing centralized and decentralized coins showing up. Perhaps a battle of the coins. Personally I am hoping that the decentralized coins win and the power structure goes to the people. A hope for humanity to get out of that old pattern. I always try to research and support coins that will support that goal.

Very interesting. I was reading it then I slept off, I woke up in morning and found myself finishing it. Amazing stunning writing and history.

Thanks for reading =)

This post has received a 16.38 % upvote from @boomerang thanks to: @itchykitten

@boomerang distributes 100% of the SBD and up to 80% of the Curation Rewards to STEEM POWER Delegators. If you want to bid for votes or want to delegate SP please read the @boomerang whitepaper.

This post was resteemed by @steemitrobot! and Got 10 Upvotes

Good Luck!

The @steemitrobot users are a small but growing community.

Check out the other resteemed posts in steemitrobot's feed.

Some of them are truly great. Please upvote this comment for helping me grow.

This post has received a 20.62 % upvote from @booster thanks to: @itchykitten, @itchykitten.

@driva has voted on behalf of @minnowpond. If you would like to recieve upvotes from minnowponds team on all your posts, simply FOLLOW @minnowpond.

Congratulations! This post has been upvoted from the communal account, @minnowsupport, by itchykitten from the Minnow Support Project. It's a witness project run by aggroed, ausbitbank, teamsteem, theprophet0, someguy123, neoxian, followbtcnews/crimsonclad, and netuoso. The goal is to help Steemit grow by supporting Minnows and creating a social network. Please find us in the Peace, Abundance, and Liberty Network (PALnet) Discord Channel. It's a completely public and open space to all members of the Steemit community who voluntarily choose to be there.

This post has received a 15.97 % upvote from @buildawhale thanks to: @itchykitten. Send at least 0.50 SBD to @buildawhale with a post link in the memo field for a portion of the next vote.

To support our daily curation initiative, please vote on my owner, @themarkymark, as a Steem Witness

Much valuable education here. Thx.