Did elves emigrate with people in the crossing of the Atlantic?

There are really two questions here: did elves survive the crossing of the Atlantic? (occasionally they did) and why didn't they usually thrive? (the degree of survival generally can't be called thriving).

![12794093_39b8_625x1000[1].jpg](https://steemitimages.com/640x0/https://steemitimages.com/DQmdHf8daSxhoK4Qsx1shNEZ3hXgXPrnx1ry5EYZRBxxeFK/12794093_39b8_625x1000%5B1%5D.jpg)

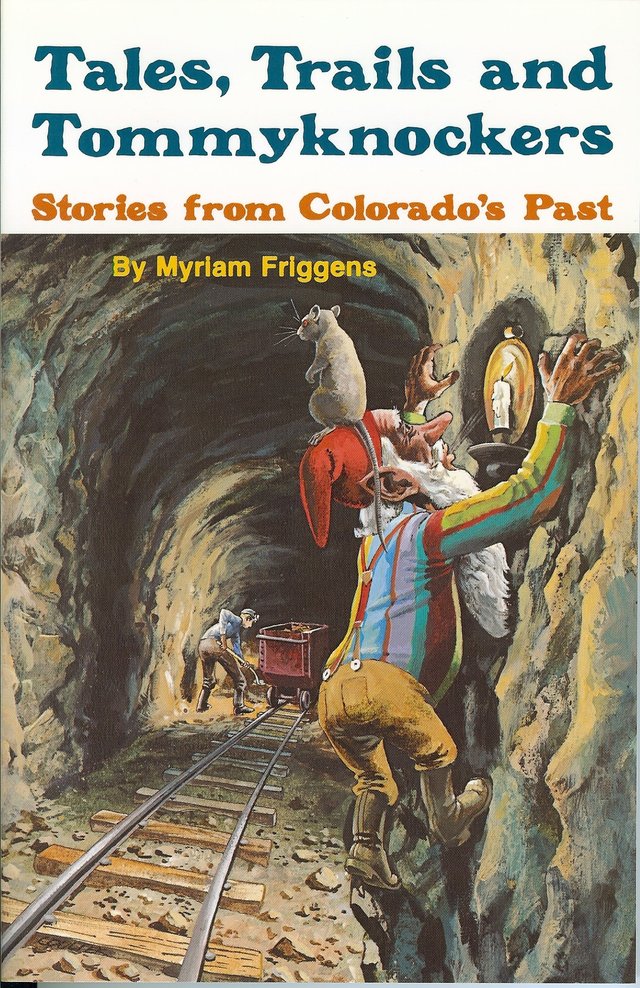

There are few examples of survivals. Peter Narvaez, The Good People: New Fairylore Essays (1991) includes an essay dealing with traditional Northern European elf beliefs in Newfoundland. In addition, I conducted research on the survival of the Cornish knockers in the American West: Ronald M. James, “Knockers, Knackers, and Ghosts: Immigrant Folklore in the Western Mines,” Western Folklore Quarterly 51:2 (April 1992). Another article can serve as an example of the sort of thing one can find scattered throughout North America: a recent account by Bill Haglund in the Nevada Journal, Nevada, Iowa - August 29, 2013 describes the survival of troll beliefs in central Iowa. The recent book, Magical Folk: British & Irish Fairies (Simon Young and Ceri Houlbrook, eds.) includes several articles dealing specifically with New World fairies, so that publication also needs to be considered.

The trolls in central Iowa can actually be regarding as thriving to a certain degree. I believe we can attribute this to concentrated clusters of Norwegian immigrants. The knockers - which became the Western Tommyknocker - is an interesting example of a European elf belief not only crossing the Atlantic and thriving but also diffusing among non-Cornish population. In 2007, I collected an account of a sighting of a Tommyknocker that occurred as late as 1952 in Golconda, Nevada from a Portuguese-American. The tradition survived in part because the Cornish were so well respected as miners that others adopted their technology, their vocabulary, and apparently their beliefs about the underground, eerie environment of the mine. The Newfoundland example can also be regarded as thriving, probably also because of a concentrated immigrant cluster.

Elf beliefs did not generally thrive, however. This is probably due to a number of factors. Immigrants often went to urban settings, and even in Europe, when rural believers migrated to cities, their beliefs typically receded. Immigrants often diffused among other groups so that they lost an ethnic critical mass in a community, and that also weakened beliefs. Where beliefs survived within the mind of an immigrant, they were not likely to be passed on to a new generation, since children will echo the belief system of their peers more than their parents (the same is general true of dialect). Because North Americans did not have deep roots and they generally regarded themselves as being part of the technological, industrial cutting edge, beliefs in traditional, pre-industrial beliefs had little room to thrive.

And finally, beliefs tend to be tied to places: the elves have always lived within that mound over there - that sort of thing. So when immigrants encountered a new environment, it was difficult to conceive of the supernatural beings as having lived in a certain spot since the new arrivals did not have anyone to tell them that this was the case. It's a complex answer to a difficult question, but these were certainly factors in why European supernatural beings did not generally thrive in the New World.

There are, of course, examples of thriving supernatural beings among North Americans, often based on Native American traditions. Here we have a situation where the people who did live in North America were able to communicate to the new arrivals that "something lives over there" or in that lake. These stories did not often make the transition and become an active belief system among the new arrivals. They often were adopted for local tourism and were regarded as "quaint" stories. Sometimes, the new arrivals adopted them completely - the bigfoot tradition is a good example.

As indicated, several articles in the new book Magical Folk discusses survivals. It is, however, too easy to cherry pick a few examples as proof that the elves made the transition. Belief did not stop with emigration, but is usually did with the next generation.

![2009_05_04_kobold-759836[1].jpg](https://steemitimages.com/640x0/https://steemitimages.com/DQmRwPZHfJTpw8GJSWvLFrpWNKWrg3S4NFhaCxuq7N8UvFH/2009_05_04_kobold-759836%5B1%5D.jpg)

Everyone has folklore and most if not all people have an active tradition involving supernatural beliefs (ghosts and angels remain active in North America, and we can include extraterrestrials in the spectrum of possible beliefs). So it was predictable that once immigrants "settled in" in their new home that they would have a belief system that included supernatural beings. The only question was regarding what they would believe in. So we have an assortment of supernatural beings in North America: for the most part, European elves (and the various creatures under that broad umbrella) failed to thrive; the widespread traditions involving ghosts and angels thrived; and some indigenous Native American beliefs diffused to the new population and thrived to a certain degree. We can even argue that the elves survived and thrived in a way: extraterrestrials are "little green men" who fly about in the night sky, abduct people, leave circles on the land, and do many other things that the traditional elf did in pre-industrial Europe.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/1w10f0/why_didnt_elves_survive_the_transatlantic_crossing/