The Genius of Hannibal

Introduction

Hannibal Barca proved to be Rome’s greatest adversary on the battlefield. He was undoubtedly talented in military warfare, but ultimately failed against the Roman will. Exaggerations have been made of his character and this paper aims to explain who he really was and whether or not he earned the title of genius. To authenticate this claim, I will investigate Hannibal’s actions in the second Punic war. I will analyze information from different sources, as well as decide if Hannibal could have been successful had he made different choices.

*Photos and diagrams coming soon: Bandwidth reached at the moment.

Hannibal faced the incredible superpower of Rome. Some say that the war was doomed from the beginning, that no man, no matter how brilliant, could have won it. Some of the major obstacles Hannibal faced include: reaching and crossing the Alps, regenerating a depleting army while keeping morale high, breaking alliances with Rome, all while winning battles against the greatest land fighting force in the world. In retrospect the task seems impossible for one man to accomplish.

Carthage

Carthage was a major power in the Mediterranean who was bound to collide with Rome as Rome gained power. Carthage was established by Phonetician traders around 814 BC, a legacy they maintained throughout their existence. They were excellent ship builders and sailors. They developed a diverse culture that gravitated around the tip of modern day Tunisia, Africa. Though they did not have a regular standing army, they hired mercenary fighters when in times of need. These fighters could be from anywhere in the known world, including Celts, Africans, Spaniards, or any type of barbarian that was willing to fight for money.

Hannibal

To begin, Hannibal was influenced by his father at a very early age. When he was just a boy of 9 years, he was made to swear an oath “not to be a friend of Rome”(Polybius 3.11). Hannibal himself was not exposed to aspects of the First Punic War, except through his father Hamilcar who resented the Romans, after losing the first Punic war. He trained his sons as “lion cubs” and may have brought some personal vendetta that influenced his sons actions based to an extent on personal reasons rather than what was best for Carthage. By adulthood, Hannibal was determined to see Rome burn to the ground.

The Second Punic War

The Second Punic War began with a Carthaginian offensive. Saguntum, a Roman city in Spain, was the catalyst to the war. Hannibal laid siege to the city and justified his aggression, claiming Seguntum violated a treaty with Carthage. Saguntum was attacking Carthage’s allies and thus responsible for the consequence(Polybius 15.5-15.8). The siege of this city played a vital role in his plan to take Rome. When the city was assaulted, Rome did not send aid to its people. This sent a message to Roman provinces, stating that if you were in trouble, no one would come to your rescue. The sack also was essential in funding Hannibal’s future expedition in hiring new mercenaries(Polybius 21.2). He was constantly losing men on the road to Rome through environmental issues andconflicts with local tribes. This was an important strategic move that made the war feasible.

Rome had beaten Carthage in the first war when Carthage was on the defensive. Hannibal changed tactics and took the offensive in the Second Punic war. He headed north and crossed the Ebro River into hostile territory while also violating treaty terms with Rome. He had to find a way to keep the morale of his men up while they endure an unknown land with a very diverse army, which would require a unique ability of influence. Many of the mercenary fighters who were recruited did not even speak the same languages among each other. By then, the Romans had responded by sending an army to Spain to fight Hannibal. They stopped to supply in Marseilles, in current day France, unaware they were close to Hannibal’s army. They expected to catch Hannibal in route and defeat him before he reached Italy Polybius (25.2).hannibals-route-of-invasion

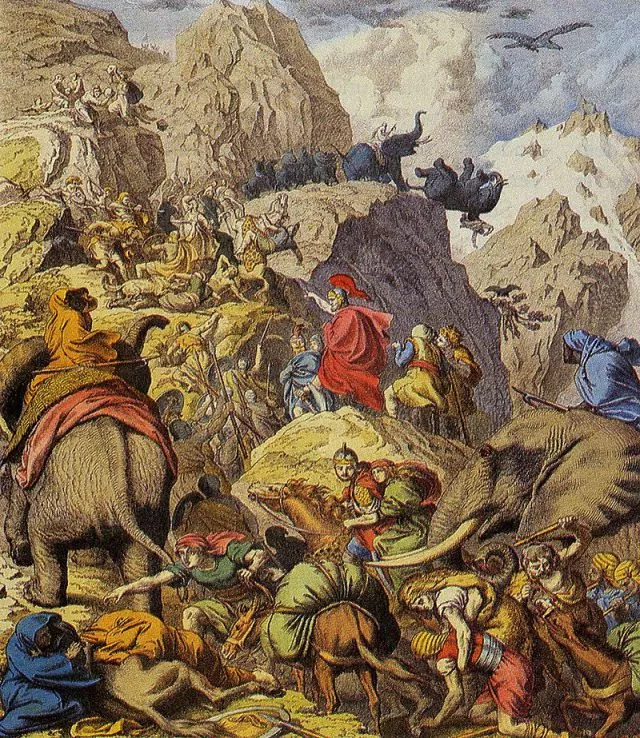

Hannibal evades the massive Roman force and a likely defeat, by heading northeast over the Alps instead of the easier more predictable coastal route. This is a bold decision that came with a complex set of risks and consequences. Hannibal decided the mountain pass was the best option. He proved to be right, however, the route was not without its challenges.

He took elephants, horses, and men through a cold highly elevated pass where many of them were lost to the weather, loose footing, and ambushes from surrounding tribes. The path descent from the Alps was problematic to say the least. The way down was steeper and harder to maneuver down. The path had been blocked by boulders and innovative techniques and strategies needed to be implemented. Livy claims that he used the expansive properties of fire and cool liquid (in this case spoiled wine or vinegar) to split them. Livy explains:

“This involved cutting away the rock, so they felled the large trees in the surrounding area, lopped off their branches, and built a huge pile of timber. They then set fire to it, getting considerable help from the strong wind, which fanned the flames. They then softened up the red-hot rocks by pouring vinegar(sour wine), into the cracks. 37.3. They then broke up the heated rocks with crow bars and made the whole slope more manageable by creating a series of gentle S-bends down the hillside. As a result both the baggage animals and the elephants were able to be led down the mountain. (37.4.)”

Polybius is our other source on the matter and does not mention specific techniques being used, however he does indicate that a high level of problem solving while navigating the descent through the Alps. Polybius is typically regarded as a more reliable historical source and claims the troops that survived the 12-day journey were numbered 12,000 African, 8,000 Spanish foot soldiers, with a maximum of about 6,000 cavalry (56.4.).Livy suggests this to be a low estimate and speculates 100,000 infantry and 20,000 cavalry, to 20,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry (38.2). It is very likely that this estimate is conceived to exaggerate the circumstances the romans were faced against in order to restore lost Roman dignity.With the journey over the Alps complete, a new phase of Hannibal’s plan is put into action. Next was the threat of the confident Roman forces to meet them in the Po Valley.

The Carthaginian forces were reduced to a third of what they once were, exhausted and in need of supply, Hannibal persuaded northern Italian Celts through a series of battles that demonstrated Hannibal’s ability, and convinced them to join his cause. With the expansion of his forces and the rest of his men, they had improving their condition for battle. As the Roman army drew near, both Hannibal and Scipio Africanus (the leader of the Roman forces) send scouting parties to gather reconnaissance. The two parties meet and Hannibal employs a successful strategy over the Roman forces and nearly killing Scipio before he was saved by his son. This event became known as the Battle of Ticinus. It was a decisive victory for Hannibal and was critical in winning the support of northern tribes in Italy and setting the stage for the battle of Trebia.

Military genius may not have been enough in Hannibal’s situation. He also needed to be more than clever, in the sense that he must maintain his army and morale while attempting to influence areas in northern Italy for more men and supplies. Morale was absolutely essential for conflicts in Italy because the Carthaginians were usually outnumbered and often the odds were stacked against them. The remarkable track record and motivational ability of Hannibal was enough to keep the diverse group of soldiers together.

After winning the battle of Ticinus, Hannibal baited the second consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus, who was known to have a temper. Hannibal began with an early morning attack using a group of a few thousand cavalry. Tiberius took the bait and charged through the freezing river into Hannibal’s trap. This is an excellent example of using the environment/timing mixed with emotional intelligence and exploitation to win the battle. Trebia was the first major battle of the second Punic War; Rome suffered a terrible loss at the hands of Hannibal. It displayed Hannibal’s ability to predict and manipulate the Roman consul into a brilliant strategic defeat that crushedthe Roman troops. Hannibal did have substantial losses but not on the scale of the Romans, similar to Hannibal’s later battles in Italy. Hannibal’s victory can be attributed to his strategic maneuvers in which Dr. Patrick Hunt of Stanford University (Hunt 6:44): explains:

Know and control the terrain

Know your enemy

Exploit your enemy’s weakness

Give your army the best tools

Ambush whenever possible

Surprise or do the unexpectedbattle_trebia-en

Dr. Hunt also claims that Hannibal had a secret weapon. He asserts Hannibal used nature to his advantage and was able to overcome tremendous odds to win battles against the Romans. He (Hunt 10:00) cites examples of:

– Crossing mountains (The Alps)

– Use Winter cold and time (Trebia)

– Cross swamps in Spring (Arno River)

– Use Summer fog (Trasimene)

– Fight at night (Ager Falernus-Volturnus)

– Use dust-blowing wind (Cannae)

The combination and implementation of this strategy and fully exploiting his“secret weapon” of nature, he earned the title of a genius in more than just military tactics.Future battles of Italy were won on these principles and integrated brilliant field maneuvers as well.

In the battle of Trasimene, Hannibal used the fog and geography to lead the Romans into an ambush. He correctly predicted that the hills would be warmer than the cool lake, thus creating a fog. The Romans came along the coast of Lake Trasimene and almost immediately found themselves in an ambush. Once helplessly caught off guard, the Romans were pushed to their death into the lake. 30,000 Roman soldiers and allies were slaughtered including Consul Flaminius, while only 1,500 of Hannibal’s men died. (Hunt 57:00) Hannibal would become famous for collecting the rings of dead Consuls (the highest elected officers of Rome, who commanded the military. This was an influential event because the Romans realized that Hannibal was a serious threat that caused Rome to change its strategy completely. Rome then tried to avoid confronting Hannibal in battle and began starving his resources.1024px-battle_of_lake_trasimene

Not long after, Hannibal was attracted to the Capuan plain, where the land was very fertile and resources were plenty. The Romans who were assured Hannibal fell victim to their trap promptly surrounded him and he would finally be defeated. Hannibal got away from the Roman army through a cleaver trick. He knew the Romans didn’t want to engage him, however he needed a distraction for escape. He usedhundreds of the cattle he recently captured in the plain, and tied flammable materials to their horns, setting them in a frenzy that looks like men with torches. The Romans fell for the trick and their guard followed the cattle while Hannibal quietly slipped away, again demonstrating his creative genius.

The battle Hannibal is most known for is Cannae. The battle is one of the most famous in history and will be remembered and studied as the single greatest military triumph. This battle demonstrates the fullness of Hannibal’s tactical genius. He uses the environment to his advantage, first choosing the battlefield with its sloped hills and dusty winds. The battle has been attempted to be re-created thousands of time throughout history in effort to mimic its success. Hannibal confronts yet again a force nearly twice his own and wins with superior tactics. He weakens his center and baits the romans inward as his strong flanks swing around to “envelop a double manifold” which crushed tens of thousands of Romans together. Polybius numbers the Roman casualties around 70,000 (117) and Livy 45,000. (47.15) The battle turned to slaughter as Hannibal destroyed nearly 1/5 of the Roman adult male population between 18 and 40. Between 25-30% of the Roman government is killed, including three consuls (two of the preceding year), two Quaestors, 29 of 48 military tribunes, and an additional 80 Senators (Hunt 1:08:32). This was an absolutely devastating battle in the eyes of the Romans. Hannibal’s plan of turning Rome’s allies against her looks more promising than ever before, as influence is won over much of southern Italy. Livy states (22.61.10):

“How much more serious was the defeat of Cannae, than those which preceded it can be seen by the behavior or Rome’s allies; before that fateful day, their loyalty remained unshaken, now it began to waver for the simple reason that they despaired of Roman Power.”

If there were ever a time in the Second Punic War to take Rome, it was now. Hannibal is aware of this fact but for some reason decides not to attack and follow his plan of gaining local support. Hannibal may have been deterred by Rome because it was well fortified, and he could not implement his brilliant tactics to the fullest in that position, as the weather and geography was in the Roman favor. Hannibal didn’t want to risk his entire campaign on an uncertain battle and using strategic thinking that made it possible, he derived that sieging Rome was not the correct move in winning the war. For Hannibal, this marked the decline of his campaign. The Romans were heavily implementing their non-confrontation strategy and it was working. Hannibal’s numbers were diminishing, and over the ten years that he remained in Italy, his army changed. Most were not the same fighters as he had crossed the Alps with. There were many fresh recruits that were not battle hardened. The result was a much different force than Hannibal’s original that he left Spain with and less capable, however faith was restored through confidence in Hannibal’s leadership.

New tactics were introduced on the Roman side to conquer the forces at Carthage, tactics that starkly resembled Hannibal’s. As a result, and against Hannibal’s wishes, the Carthaginian Senate requested Hannibal’s return. Scipio had mimicked Hannibal’s offensive strategy and provided an immediate threat to Carthage provoke Hannibal’s swift return. Scipio’s plan worked and the two armies met at Zama, a city southwest of Carthage. There is much debate as to the details of the battle but one thing is certain, that Hannibal was not able to conclude with a victory like those in the past. However, some historians do not believe that Hannibal was defeated as badly as some Roman sources may claim. Mosig and Belhassen question the accuracy of the battle in a few ways, the first being elephants used in the battle. It is said by Livy, that “no fewer than 80 elephants”(Livy 30:33). They point out that this was much more than the assaulting force in the Alps, and that Carthage would have likely used them in Utica prior to Zama. This idea of the elephants and their ingenious defeat at the hands of Scipio’s tactics seems farfetched. It seems more likely that Livy added those details to exaggerate Scipio’s victory and demonstrating Romans could overcome Hannibal’s most fearsome beasts. At one point in the battle, it would appear that Hannibal was making a very convincing effort to win the battle. The dynamic changed when Masinissa and Laelius, Numidian exiles and friends of Rome, came crashing into Hannibal’s rear to quickly end the fight. According to Mosig and Belhasssen;zama

“The lost battle was certainly not due to the generalship of Publiys Cornelius Scipio, nor to an error on the part of Hannibal, but to sheer lick and the presence of Masinissa, without whom the Romans would most certainly have been doomed.”(178)

Livy notes that, “Scipio was undoubtedly aware that he would have been defeated had he not been saved at the last moment by Masinissa, later acknowledged that Hannibal had done at Zama everything anyone could have done (Livy 30:35, 5-8). Mosig and Belhassen also suggest, “for his cavalry been 30 minutes later in returning to the battlefield, Zama would, most probably, have been added to the string of Hannibal’s victories”(178).

With these supporting ideas, I would assert that major mistakes were not made by Hannibal toward the end of the Second Punic War. He seemed to have been following orders and doing the best he could with what he had and does not reflect an poor decision making. I support the idea that Hannibal was a genius. He was a genius in every sense of the word; he fully exploited his resources and continues to baffle military experts today with his strategies and tactics. It is important to note, that being a genius does not guarantee success. The standard definition of a genius is someone who is at the top 2% of human intelligence, or about 1 out of every 50 people. By this standard, many people in the ancient world were indeed geniuses; they lacked the opportunity and access to resources in which to fully exploit their talents as Hannibal did. It can also be argued on that premise that Hannibal was not presented with the right circumstance, that he too was cursed with bad luck and circumstance suggesting that he could win almost every battle and still lose the war. Hannibal did not have the full support of Carthage, but used what he had to the fullest extent. Judging Hannibal Barca according to this scale, I would assume he is more of a super genius of sorts. His abilities have been unmatched, surviving the test of time as they continue to be studied and taught my military tacticians today, which puts him at much larger odds than a meager 1/50th. His genius is displayed through not only the brilliant battles fought against the Romans, his ability to exploit people and places, and his charismatic appeal, but more importantly how Rome reacted and changed after dealing with the great man. Rome no longer used farmers as soldiers, but rather trained professionals as Hannibal did. They also developed new military structures, tactics of warfare, and rules of engagement. Hannibal was the greatest military general the world has ever seen and his ideas continue to set precedent for strategic behavior around the world nearly 1,800 years after his death.

For the fully cited version : hannibal-research-paper

Bibliography

Livy, Aubrey De Sélincourt, and Betty Radice. The War with Hannibal: Books XXI-XXX of The History of Rome from Its Foundation. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972. Print.

Polybius, and W. R. Paton. The Histories. London: Heinemann, 1960. Print.

Hunt, Patrick, Dr. “Great Battles: Hannibal’s Secret Weapon in the Second Punic War.” YouTube. Ed. Stanford University. YouTube, 07 June 2013. Web. 03 Apr. 2014.

Mosig, Yozan D., and ImeneBelhassen. “Revision And Reconstruction In The Second Punic War: Zama–Whose Victory?.” International Journal Of The Humanities9 (2007): 175-186. Humanities International Complete. Web. 3 Apr. 2014.

Porter, Barry. “At Lake Trasimene, Hannibal Barca Combined Tactics And Psychology To Destroy A Roman Army.” Military History4 (2001): 12. MasterFILE Premier. Web. 3 Apr. 2014.

Advertisements

Let me know when it is done, so I can have the post reviewed and curated:)

Thank you :) (steemstem curator)