Kimble [Kimball] Bent An Unusual European Who Deserted The British Army And Joined The Hau Hau #36

A story related by Bent is illustrative of the Maori belief, up to quite modern days, in malignant beings which made their homes in lonely waters and in caves, the dreaded taniwha.

The tale of the “Taniwha” of the Kopua,

One day, this was in the early “seventies”, an old man named Te Maire left the Kawau landing in his canoe and paddled down the Waitara to a place called Te Kopua, the site of an ancient village.

The object of his expedition was to procure dry resinous strips of the rimu-pine for the purpose of making torches to be used in catching piharau (lampreys) in the river at night.

After getting the wood he required he started on the return paddle to his home.

On the way to the Kawau, he disappeared and was never seen again alive, no doubt he overbalanced and fell into the river while poling his canoe up one of the small rapids near the Kopua.

That afternoon five men from the Kawau, including Kimble Bent, were paddling their canoe down the river to a settlement a few miles distant when they caught sight of the old man's empty canoe drifting down with the swift current.

As they approached it sped away rapidly before them, and at last stranded on a shingle-bank in a bend of the river.

In it, they found Te Maire's gun and a young pig, which the vanished man had evidently caught in the bush while on his torch-making expedition.

Bent's Maori companions immediately explained in their own way the mystery of their tribesman's disappearance.

“There is a taniwha there,” they said, “a fearful water-monster that dwells in a deep, still pool under Te Kopua's banks.

He has stretched forth his long claws and dragged the old fellow down to his den.”

The Maori canoeists made haste to quit the dead man's craft and plied their paddles with unusual energy until they reached their destination on the shore below.

They told their story, and that evening a meeting of the village people was held in the whare puni to discuss the mystery.

For hours the wiseacres of the bush-hamlet solemnly debated the circumstances, and each canoeist, in turn, had to give his account of the affair and advance his theory.

At last, it was decided that there was no possible doubt that the taniwha of the river had seized Te Maire and drowned him.

There must, of course, be a reason, for no taniwha of any repute would take such an extreme step without some good cause.

The verdict was that Te Maire had violated the tapu of the deserted village, he had in all probability taken some dry rimu from an old house that stood there, and which was sacred because a chief had died in it, goodness knows how long ago.

The river-god had very properly punished him with death, it was the penalty of infringing the law of tapu.

The next day and for some days thereafter canoe crews hunted the river for the old man's body but found it not.

At last a woman at the lower settlement, going down to the river one morning to get a calabash of water, spied the body of the missing man hanging in the branches of a prostrate kahikatea-tree on the opposite side of the river, about four feet above the water.

The question was, how did the body get there, entangled in the branches that height above the river, for there had been no flood, no noticeable rise or fall in the level of the river.

The answer was plain to the mind of the Maori. He summed it all up in two words,

“Te taniwha!”

The river-monster, after grabbing Te Maire from his canoe and detaining him a while in his watery grave, had dragged the body away down-stream and hung it up in the tree-branches opposite the village, so that the dead man's people should have no difficulty in recovering it, and in giving it a decent burial.

A truly thoughtful and considerate taniwha.

At last, about the year 1876, the Upper Waitara was sold to the Government.

The white man and his Maori people cried their farewells to Ngati-Maru and journeyed back over the ranges and through the forests to their old lands in the valley of the Patea.

Bent was still Rupe's servant.

The old chief and his household and some Hauhau relatives, armed, and carrying their belongings on their backs, trudged through the wilderness until they reached Rukumoana, their old-time shelter-camp on the banks of the Patea, about thirty miles from the sea.

Here they halted and built their hamlet of saplings and thatch, and an old overgrown clearing was burnt off and planted with potatoes and maize.

The party was but a small one.

Besides Bent, there were Rupe, his wife, and their two sons, old Hakopa and his wife, and their niece, a girl named Te Haurutu-wai (“The Breeze that shakes the Raindrops down”).

It was an even lonelier spot than the refuge-camp in the Ngati-Maru country, life here was simple and primitive in the extreme.

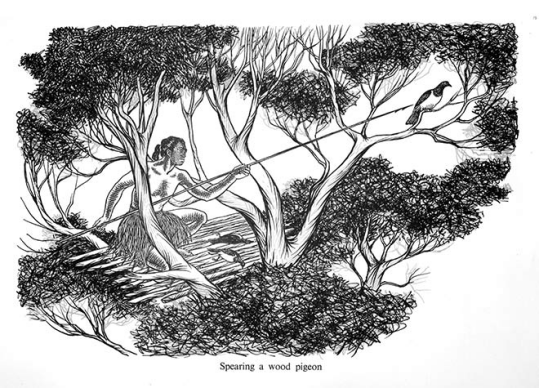

The people tended their little plots of food-crops, shadowed by the dark forest, they snared and speared the forest birds, they hunted the wild pig and climbed the hollow trees for wild honey.

For nearly two years the pakeha-Maori lived with his little tribe in Rukumoana.

The ancient customs of the Maori fowler's cult were observed by these bush-dwellers, brown and white.

For instance, the first kaka parrot

or tui

or other forest creature snared or speared in a day's birding was not eaten, but was left, as an offering to the gods of the forest, beside an old tapu canoe which was lying in the bush close to the river-bank.

It was a hoary relic, this ancient waka tapu, a carved dug-out covered with long grey moss.

It was a small canoe, eight or ten feet long, and had lain there for years and years filled with water.

Somewhat similar canoe-shaped troughs, filled with water, stood in various places in the forest, these were filled with water and were generally placed in spots remote from streams or pools.

Above them slip-knot snares were arranged, so that the pigeons and tui and other birds, flying down to quench their thirst after feeding on the miro or hinau or tawa berries, were caught in the nooses, and hung there, flapping and helpless, until the fowlers went round to collect the day's bag.

This canoe was called a waka-whangai, or wai-tuhi.

When spearing birds with the long barbed spear of tawa-wood, the hunter would take great care to avoid getting any blood on his hands in withdrawing the weapon from the bird's body.

Should blood stain the hands, ” kaore e mana te tao “, the spear would lose its bird-killing powers, it would be an unlucky affair altogether, and the forest-man might as well throw it away.

Such were the beliefs of the dwellers in those dim forest-places.

At the end of the first harvest season Rupe led his white man out into the forest one day, and, halting before a tall, straight totara-pine that grew near the steep bank of the Patea, he said,

“This is my canoe, Hew it down and carve it out! In it, we will paddle down the river to Huka-tere, and you shall look upon the faces of your fellow-pakehas again.”

So now behold Bent the canoe-builder.

There above him towered the tree, Tane the Forest-god personified.

In his hand was his broad-axe, with it he must make his rangatira's river-boat.

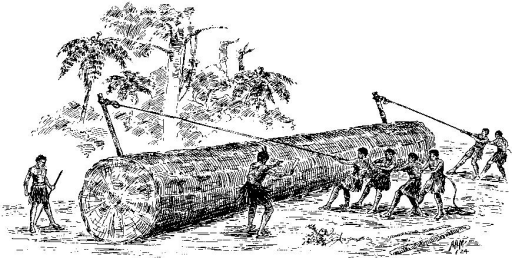

He felled the tree, and, lopping off the upper part, began the laborious work of dubbing out the waka.

The upper side of the trunk he levelled off with his axe, and then he gradually cut it into hollowed shape, an art he had learned on the Waitara.

For this portion of the work, an adze was chiefly used, a steel blade lashed to a wooden handle in the old Maori fashion.

He trimmed and shaped the ends into bow and stern, and day by day the canoe assumed more shapely proportions, until at last, it lay complete, a craft of about twenty-five feet in length and three feet in beam, rough and undecorated, it is true, but still a ship of the Maori, fit to carry cargo and paddlers, and run the rapids of the swift and broken Patea.

Ropes were made of stout supplejack vines, and with Rupe and his family, the white man lowered the canoe down the high bank to the water-edge.

Te Riu-o-Tane lay ready for its crew, the Hollow Trunk of Tane.

Then paddles were shaped out,

and Bent and his companions set to work catching and drying eels and gathering wild honey, in preparation for the voyage down the river to Hukatere village, where the main body of Rupé's tribe resided.

About this time the white man entered upon his third matrimonial experience.

His chief's grand-daughter, a good-looking girl of about eighteen, came to the little village with a visiting party of Ngati-Ruanui.

She had already a husband, but he had quarrelled with her, and attempted to kill her, she, therefore, returned to her old tupuna, Rupe, who now gave her to Bent, and the white man and his young Maori wife lived happily there in well-hidden Rukumoana.*

[This name Rukumoana originated thus, according to the Maoris,

About the year 1830, a war-party from the Waikato attacked and slaughtered a number of Taranaki people here.

One of the Taranaki's saved his own life and that of his brother in a remarkable manner.

These two men were cousins of Hakopa, the old warrior who befriended Kimble Bent in Te Ngutu-o-te-Manu pa in 1868, and later on the Waitara.

One of the men was wounded, and in another moment his head would have been slashed off by a Waikato savage, but his brother seized him in his arms and leapt over the steep bank of the Patea into the river below.

He dived to the bottom, and still holding his brother, crawled along the bottom until he reached a place under the banks where the overhanging shrubs concealed them from view.

The pursuers failed to find the brothers, who presently escaped to the forest.

The Taranaki people commemorated this heroic deed by naming the spot where Hakopa's cousin took his daring leap “Ruku-moana” (“Deep-Sea Diving”).]

The first of the below posts has a list of the previous posts of Maori Myths and Legends

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/how-war-was-declared-between-tainui-and-arawa

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-curse-of-manaia-part-1

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-curse-of-manaia-part-2

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-hatupatu-and-his-brothers

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/hatupatu-and-his-brothers-part-2

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-the-emigration-of-turi-an-ancestor-of-wanganui

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-continuing-legend-of-turi

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/turi-seeks-patea

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-manaia-and-why-he-emigrated-to-new-zealand

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-love-story-of-hine-moa-the-maiden-of-rotorua

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/how-te-kahureremoa-found-her-husband

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-magical-wooden-head

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-art-of-netting-learned-from-the-fairies

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-kanawa-s-adventure-with-a-troop-of-fairies

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-loves-of-takarangi-and-rau-mahora

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/puhihuia-s-elopement-with-te-ponga

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-story-of-te-huhuti

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-trilogy-of-wahine-toa-woman-heroes

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-modern-maori-story

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/hine-whaitiri

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/whaitere-the-enchanted-stingray

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/turehu-the-fairy-people

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/kawariki-and-the-shark-man

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/awarua-the-taniwha-of-porirua

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/hami-s-lot-a-modern-story

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-unseen-a-modern-haunting

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-death-leap-of-tikawe-a-story-of-the-lakes-country

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/paepipi-s-stranger

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-story-of-maori-gratitude

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/by-the-waters-of-rakaunui-1

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/by-the-waters-of-rakaunui-2

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/bt-the-waters-of-rakaunui-3

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/bt-the-waters-of-rakaunui-4

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ake-s-revenge-1

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ake-s-revenge-2

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ake-s-revenge-3

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ake-s-revenge-4

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/some-of-the-caves-in-the-centre-of-the-north-island

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-man-eating-dog-of-the-ngamoko-mountain

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-story-from-mokau-in-the-early-1800s

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/new-zealand-s-atlantis

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-cave-dwellers-of-rotorua

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/kawa-mountain-and-tarao-the-tunneller

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-fragrant-leaf-s-rock

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-from-the-waikato-river

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/uneuku-s-judgment

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/at-the-rising-of-kopu-venus

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/harehare-s-story-from-the-rangitaiki

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/another-way-of-passing-power-to-the-successor

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-cave-of-wairaka

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-of-how-mount-tauhara-got-to-where-it-is-now

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ana-o-tuno-hopu-s-cave

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/stories-of-an-enchanted-valley-near-rotorua

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/utu-a-maori-s-revenge

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/where-tangihia-sailed-away-to

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-curse-on-te-waru-s-new-house

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-fall-of-the-virgin-s-island

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-first-day-of-removing-the-tapu-on-te-waru-s-new-house

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-maori-detective-story

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-second-day-of-removing-the-tapu-on-te-waru-s-new-house

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-story-of-a-maori-heroine

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-from-old-kawhia

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-stealing-of-an-atua-god

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/maungaroa-and-some-of-its-legends

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-mokia-tarapunga

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-memory-of-maketu

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-from-the-taupo-region

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-of-the-taniwha-slayers

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-witch-trees-of-the-kaingaroa

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/there-were-giants-in-that-land

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-from-old-rotoiti

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-lagoons-of-the-tuna-eels

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-takitimu

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-white-chief-of-the-oouai-tribe

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/tane-mahuta-the-soul-of-the-forest

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-of-maori-magic

with thanks to son-of-satire for the banner