The Vikings – Traders Before Raiders

source image

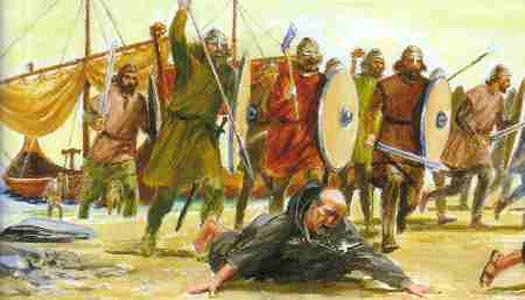

The Viking attack on the monastery at Lindisfarne in 793 C. E became the ‘official’ beginning of the Viking Age, and set the precedent for what they would most popularly be known for - raiding. But they were also traders, and had been for possibly many centuries prior. Up until the Viking Age the majority of their trading would most likely have occurred by overland or short sailing trips, but things happened which made it possible for the coastal-based Scandinavians to undertake longer expeditions, such as improvements to boats and navigational skills. Political and religious upheavals saw people depart their homelands in order to be free of subjugation, and while moving away, keeping ties with their homelands, thus increasing ports from which to trade both with people back home and in new territories. It would have been a somewhat natural progression, for people not adverse to adventure on the seas, to move from trading to plundering the riches of countries experiencing economic growth.

image source

A clue to what came first for the Vikings might be found in the etymology of their name. ‘Viking’, which, according to several experts, may well mean ‘someone who frequents viks’, with viks equating to wics, the trading centres around Northern Europe.1 Another expert, though, puts the origin of the name Viking at the Swedish coastal strip near Götha called Viken,2 situated north of Denmark, one of the main points from which the Swedes worked their sea-based operations of trading and raiding; and this theme may be reiterated in a place name in the Faroes – Vik,3 which means bay - settled by Vikings. ‘Trading’ seems to fit existing archaeological and written evidence, which have both shown that ‘[s]ince the beginning of the second millennium B.C. Scandinavia had experienced the successive phases of the European culture existing south of it, and this could not have happened without trade and traders.’4 And even earlier still, ‘[a]ncient implements, weapons, coins and pottery found in Sweden prove that the inhabitants entertained trade relations with their neighbo[u]rs on the European continent as early as 6,000 B. C’5, with their main exports being furs, wool, dried fish, iron, and horses. Coins were found which indicated trade between other countries during ancient times, much earlier than the era of the Viking’s first documented raiding during the eighth century C. E. Also during the eighth century C.E much of Northern Europe experienced economic prosperity, with the growth of existing - and creation of new - trading centres and trading routes. This meant there were far more opportunities for the Vikings to begin piracy and extortion – although sometimes they were on the receiving end of raids and tribute-demands by neighbouring countries or those along the trading routes.6

image source

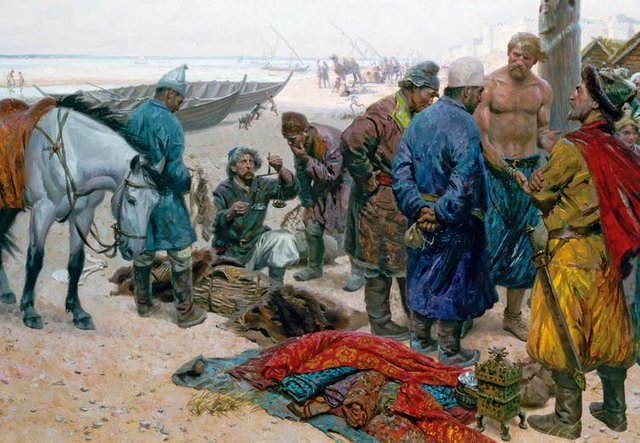

‘A key factor in the outburst of piracy was … the commercial expansion in north-west Europe that had begun over a century before the first reported raids.’7 In fact, one really had to know that a place existed in order to plan a raid on it, and that there was anything worth raiding. This idea was enforced by one historian when he stated ‘their contacts with western merchants enabled Scandinavians to learn about Europe’s wealth’.8 They did not have to establish a connection with all places they raided, but they most likely would have at least traded for information about possible targets, how much and what kind of wealth was available and how well defended the area was. The only assured booty of an inhabited area was likely the inhabitants themselves, who could then be ransomed back or sold as slaves. According to one historian,

…the great recruiting grounds for slaves were war, piracy, and trade. They came in great numbers from the British Isles, either caught in the dragnet of the Viking raids and invasions or as straightforward objects of commerce; they came from all other countries where Viking power reached; and above all they came from slave-hunts among the Slavonic peoples whose countries bordered on the Baltic…the demand from Spain and the remoter Muslim world was insatiable… the slave-trade was essential to Viking commerce …9

image source

Perhaps what began as peaceful trading of goods in ports and harbours found during fishing expeditions turned into lucrative ransom-collecting, tribute-demanding, or slave-capturing raids as both the demand for, and profit from, slavery became one of the largest marketable commodities. According to the Annals of Ulster, in 871 Vikings returned to their trading base in Dublin ‘bringing away with them in captivity … a great prey of Angles and Britons and Picts’10 and previously to that, around 860, after an expedition to Spain and North African coastal regions ‘carried off a great host of them as captives to Ireland’.11 In this regard, trading and raiding began to be heavily interlinked.

image source

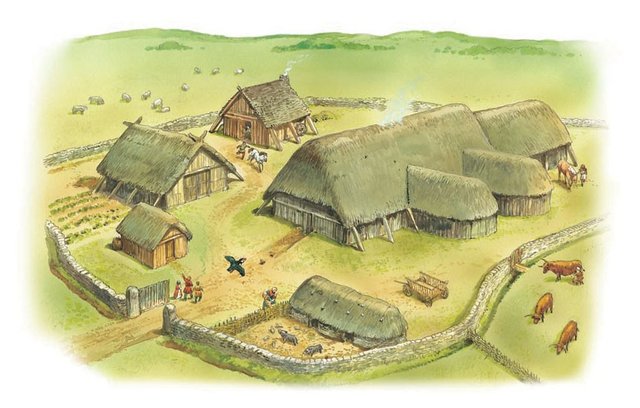

It is possible that one reason for expanding their sea-based explorations was a need to look further afield for food during their fishing expeditions. A majority of Scandinavians were coastal-based, borne from the rather poor farming-type land and rugged terrain on which they lived. One historian stated that it seemed ‘implausible that a people which emigrated because of land-hunger should have settled in places so difficult for agriculture as the Orkneys, Shetlands, Faroes, or Iceland’12 although other historians pointed out that there were areas of very fertile land throughout parts of Scandinavia. One expert also suggested that it was new fishing grounds for herring supplies they were searching for, herring being a major part of their staple diet. As they also hunted and ate whale meat, it was possible the Vikings had to start looking further afield for the whales, which were probably also a great tradeable commodity. Then, in some of the more remote and less productive areas where the Scandinavians emigrated to, they may have needed to trade for goods they could not grow or make themselves, and what they had to offer most readily came from the sea. Although, a group of historians researching the Faroe Islands - one distant place of Viking settlement - thought that the earliest settlers were farmers seeking land, as they’d taken farm animals and cereal crop seeds with them.13

image source

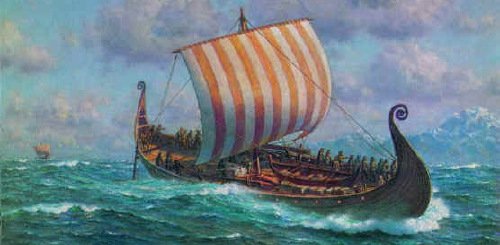

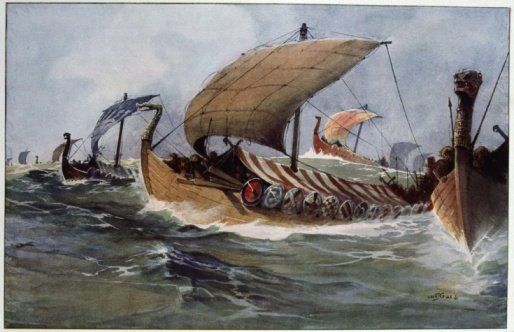

While they traded with – and even settled in - territories on the mainland of northern Europe, their strength lay on and around the water, and they were happiest seeking adventure at sea, and therefore settling more in coastal regions. This may have been the reason for their greater expansion efforts to the west, rather than the east, although the convenience of lower populations may have been a logical factor – why try and take over an area more densely populated when there were places of little or no current habitation but would still suit their needs. What enabled them to even contemplate venturing further than the waters around Norway, Sweden and Denmark was the development during the eighth century of their ‘shipbuilding techniques’ as well as their ‘seafaring skills’ which ‘enabled them to travel safely and reliably through the open ocean’14 The Scandinavian’s built different types of ships, indicating a variety of reasons behind their sea travel. They designed and developed shapes and structures of boats for particular needs, such as war, fishing, travel, or trade; and for both short-distance and long-distance voyages. In both Norway and Sweden, most people settled near the coast, or large bodies of water, and most parts of Denmark were near enough to coastal areas that the sea and sailing was a natural part of everyday life. So rulers in Scandinavia, more so than other nearby countries, held authority not only on land, but over shipping and the sea-lanes, whereby a king’s prestige ‘consisted of sea-power and the ability to employ this for conquest and profit.’15 The Vikings mastery of the open seas and distance travel came after technological advancements in both navigational skills and ship design, including the development of sails. ‘Without sails, the Vikings’ far-flung exploits would have been impossible.’16

image source

It may be a difficult point to prove the true motivation behind early Viking expeditions which led to settlements and bases from which to trade – expansion of territory, seeking food sources, hunger for wealth are all possible conclusions. By studying writings and archaeological finds, experts have concluded that the Scandinavians had been trading for centuries before their first documented raids. It seems logical to conclude that trading would have occurred before raiding, as raiding may have been a progression from the building up of wealth from trading, and until that occurred, there was little incentive to raid, apart from perhaps the lucrative slave market. But still, first they had to know there were new territories, and then whether there was anything worth obtaining – by trade or raid – and they were in a good position to do either, as they were confident, adventurous sea-loving people.

This essay was one I wrote as an assignment, while obtaining my University degree. I have included the reference list and bibliography - reference materials I used while writing - just as I’d had to for its submission. It has never before been published anywhere public, though. Images have been added for visual interest.

References

1 James, Edward. Britain in the First Millennium. Britain and Europe. London: Arnold, 2001, pp. 218

2 Roos, William. "The Swedish Part in the Viking Expeditions." The English Historical Review 7 26 (1892), pp. 214

3 Arge, Simun V., et al. "Viking and Medieval Settlement in the Faroes: People, Place and Environment." Human Ecology: Historical Human Ecology of the Faroe Islands 33 5 (2005), pp. 611

4 Jones, Gwyn. A History of the Vikings. Oxford Paperbacks. Rev. ed. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, 1984, pp. 157

5 na. "Vikings Were Business Men." The Science News-Letter 12 336 (1927), pp. 191

6 Roesdahl, Else. The Vikings. 2nd ed. London New York: Penguin Books, 1998, pp. 189

7 Sawyer, P. H., ed. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 3

8 ibid., pp. 7

9 Jones, Gwyn. A History of the Vikings. Oxford Paperbacks. Rev. ed. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, 1984, pp. 148

10 James, Edward. Britain in the First Millennium. Britain and Europe. London: Arnold, 2001, pp. 221

11 ibid., pp. 222

12 Davis, R. H. C. A History of Medieval Europe: From Constantine to Saint Louis. Second ed. Harlow: Longman Group UK, Ltd, 1988, pp. 167

13 Arge, Simun V., et al. "Viking and Medieval Settlement in the Faroes: People, Place and Environment." Human Ecology: Historical Human Ecology of the Faroe Islands 33 5 (2005), pp. 615

14 Bentley, Jerry H., Herbert F. Ziegler, and Heather E. Streets. Traditions & Encounters : A Brief Global History. Boston: McGraw Hill Higher Education, 2008, pp. 254

15 Jones, Gwyn. A History of the Vikings. Oxford Paperbacks. Rev. ed. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, 1984, pp. 152

16 Roesdahl, Else. The Vikings. 2nd ed. London New York: Penguin Books, 1998, pp. 83

Bibliography

Arge, Simun V., et al. "Viking and Medieval Settlement in the Faroes: People, Place and Environment." Human Ecology: Historical Human Ecology of the Faroe Islands 33 5 (2005): 597-620. Print.

Arnold, Martin. The Vikings : Culture and Conquest. London New York: Hambledon Continuum, 2006. Print.

Bentley, Jerry H., Herbert F. Ziegler, and Heather E. Streets. Traditions & Encounters : A Brief Global History. Boston: McGraw Hill Higher Education, 2008. Print.

Bruun, Per. "The Viking Ship." Journal of Coastal Research 13 4 (1997): 1282-89. Print.

Cross, S H. "The Scandinavian Infiltration into Early Russia." Speculum 21 4 (1946): 505-14. Print.

Davies, Norman. Europe: A History. 1996. London: Pimlico, 1997. Print.

Davis, R. H. C. A History of Medieval Europe: From Constantine to Saint Louis. Second ed. Harlow: Longman Group UK, Ltd, 1988. Print.

Forte, Angelo, Richard D. Oram, and Frederik Pedersen. Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. Print.

James, Edward. Britain in the First Millennium. Britain and Europe. London: Arnold, 2001. Print.

Jones, Gwyn. A History of the Vikings. Oxford Paperbacks. Rev. ed. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, 1984. Print.

Logan, F. Donald. The Vikings in History. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge, 2005. Print.

na. "Vikings Were Business Men." The Science News-Letter 12 336 (1927): 191. Print.

Blood of the Vikings. 2001. Levy, Suzanne, Sam Roberts and Liz Tucker.

Roesdahl, Else. The Vikings. 2nd ed. London New York: Penguin Books, 1998. Print.

Roos, William. "The Swedish Part in the Viking Expeditions." The English Historical Review 7 26 (1892): 209-23. Print.

Sawyer, P. H., ed. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. Print.

You received a 60.0% upvote since you are a member of geopolis and wrote in the category of "geopolis".

To read more about us and what we do, click here.

https://steemit.com/geopolis/@geopolis/geopolis-the-community-for-global-sciences-update-4

Thank you, I appreciate it. :)

This is a curation bot for TeamNZ. Please join our AUS/NZ community on Discord.

For any inquiries/issues about the bot please contact @cryptonik.

Beautiful article.

Thanks.

Interesting to learn a new etymological origin for the word Viking!

Great amount of references, but a little low on the picture referencing: let's at least give Sergey Ivanov a mention for the paintings (took a while to figure that out, although I vaguely recalled this painter from somewhere).

What's your take on how far the Vikings went: all the way to Mexico? My tour guide of one of the pyramids was convinced they had. We tourists all remained a little sceptical....

Excellent post. I love the history of the vikings. As an underwater archaeologist. I have been fascinated with the history of their maritime activities and coming to New World. Thanks for the post.

Nice story, how times have changed. Imagine the calm descendants that have come from the lineage of the Vikings and how peaceful they have been living.

@ravenruis the Vikings definitely left there marke on Europe ant the middle eaast. I found the fact that some of them left graffity in the Agia Sofia in Istanbul in rune letters