Meet Dawn, a 9,000-year-old teenage girl .

© Reuters The angry face of Dawn is on display at the Acropolis Museum in Athens

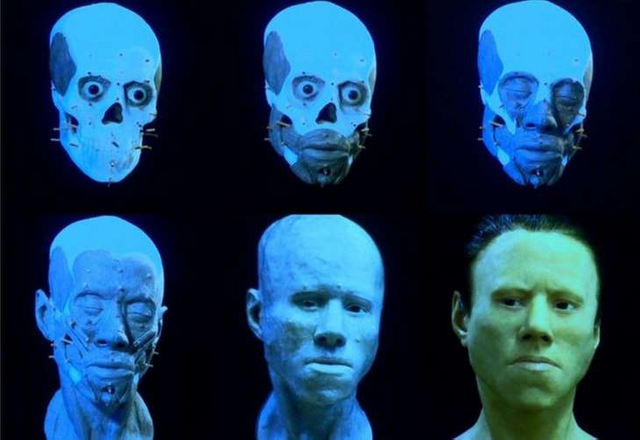

This is what Dawn may have looked like when she was alive, 9,000 years ago.

The face of a girl, thought to be aged between 15 and 18, has been recreated by scientists based on remains found in a cave in Greece in 1993.

The silicone model was created using CT scans and 3D printing technology.

She was named Avgi, Greek for Dawn, because she lived in the Mesolithic period in about 7,000 BC, considered by some to be the dawn of civilisation.

According to researchers at the University of Athens, her remains suggest that:

She had a protruding jaw, which could have been caused by chewing on animal skin to make it into soft leather

Dawn suffered from anaemia, lack of vitamins and possibly scurvy

She could have struggled to move because of hip and joint problems, which could have contributed to her death

Her bones indicated she was 15 when she died, but the teeth suggested she was 18. Other features like skin and eye colour were inferred based on general population traits in the area.

Greece displays '7,000-year-old enigma'

Long-lost Greek temple mystery solved

Mysterious Dead Sea Scroll deciphered

As for her apparently angry look, orthodontics professor Manolis Papagrikorakis told Reuters news agency: "It's not possible for her not to be angry during such an era."

© Reuters The process of reconstructing Dawn's face

Her remains were found in Theopetra Cave, in the central Greek region of Thessaly, where objects from Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic periods have also been discovered.

The reconstruction work involved an international team and a Swedish laboratory specialising in human reconstructions.

The face is on display at the Acropolis Museum in Athens.

A group of archaeologists have ended a search lasting more than 100 years for a missing Greek temple, after working out that ancient directions to the site were wrong.

In 1964, a Greek and Swiss team began digging at the Eretria site on the island of Euboea, which "other archaeologists had been excavating in vain since the 19th century", Greece's ERT public broadcaster reports.

They were looking for a legendary temple to the Goddess Artemis, one of the most widely-venerated deities of Ancient Greece, as described by the geographer Strabo, who died early in the 1st century CE.

He said the open-air sanctuary stood seven Greek stades (1.5 km; about one mile) from the site of ancient Eretria. But Swiss archaeologist Denis Knoepfler discovered stones characteristic of Greek buildings of the time had been reused in a Byzantine church, and calculated that Strabo was mistaken, Swiss Radio and Television reports. He suggested a distance of 11 km (6.8 miles) instead.

So the team from the Swiss Archaeological School and Greek Archaeological Service switched the dig to a site at the foot of a hill near the small fishing village of Amarynthos. After painstaking work, they discovered a stoa, or gallery, that could have formed part of the temple, and began excavating in earnest in 2012.

Their analysis proved correct, when the team finally "cut through the gallery walls this summer to reveal the core of the sanctuary of Amarysia Artemis", the Greek Culture Ministry said.

The team has since uncovered buildings ranging from the 6th to 2nd centuries BCE, including an underground fountain, and, crucially, inscriptions and coins bearing the name Artemis - the guardian goddess of Amarynthos. "These confirm that the site was the destination for the annual procession from Eretria by local worshippers of the goddess of the hunt", says the local website EviaZoom.

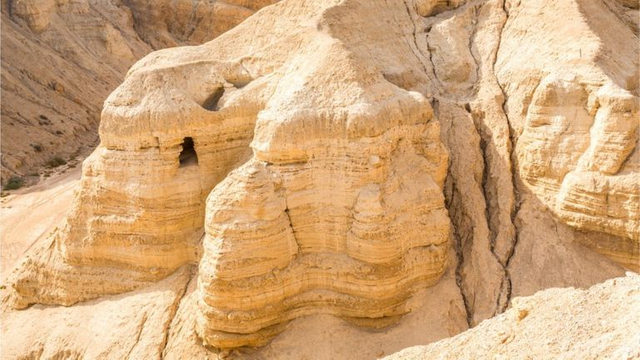

Mysterious Dead Sea Scroll deciphered in Israel

One of the last remaining obscure parts of the Dead Sea Scrolls has been deciphered by researchers in Israel.

Sixty tiny fragments were pieced together over a period of a year, identifying the name of a festival marking the changes between seasons.

It also revealed a second scribe corrected mistakes made by the author.

The 900 scrolls, written by an ancient Jewish sect, have been a source of fascination since they were first discovered in a cave in Qumran in 1947.

The collection is considered the oldest copy of the Hebrew Bible ever found, dating to at least the 4th Century BC.