In what ways did the post-Versailles order augment ethnic tensions? Part 2.

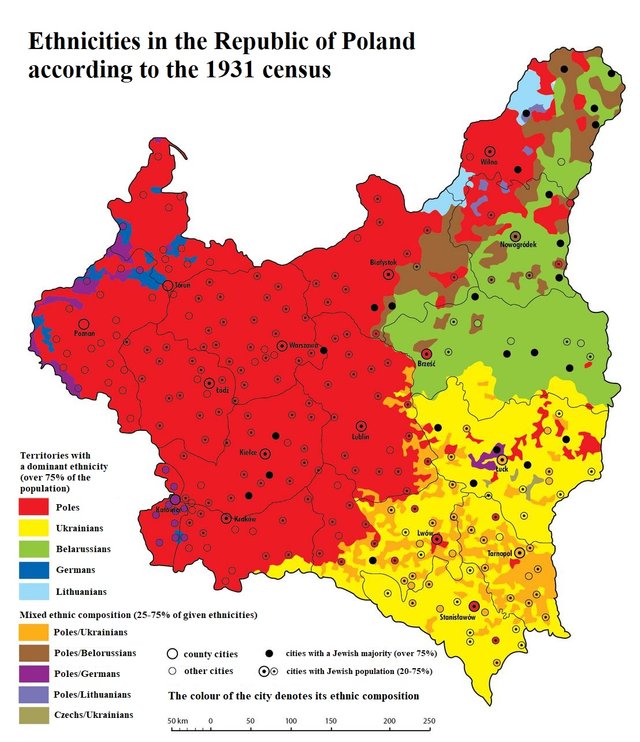

While Hungarians strived to regain a multinational state, the young Ukrainian nation was determined to form a state for the first time in history. The partition of Ukraine between two new political organisms, Poland and Bolshevik Russia in 1921 in Riga concluded a war, yet confronted Ukrainians with the reality that the right to self-govern exists only when defended both by military successes and unchallengeable historical claims. While Poland was sympathetic of the formation of a Ukrainian buffer state, the joint Petrula-Piłsudski Kiev offensive of 1920 failed to wrest Ukraine from the Bolsheviks, and Ukrainian historical argumentation was exaggerated at best, by far not convincing enough to secure the support of great powers. [1] Ukrainians as a nation found themselves in a most undesirable position. The Polish step up as a well-developed society possessing a ruling class and intelligentsia although with their statehood newly acquired. [2] While the more urbanised regions of the young Polish Republic transitioned from an ethnic and cultural community to a society within a state without major problems, the mostly rural-dwelling Ukrainians, while making frantic attempts to gain sovereignty against all odds, were but in the concluding stages of becoming a nation proper: searching for and spreading national identity, values and heroes.

In my opinion the establishment of borders was a significant factor for the quickening of Ukrainian national identity and its spread from Ukrainian intelligentsia to Ruthenian peasantry. The class stratification of the Ruthenian ethnic element required to form a proto-nation was, most generously asserting, only a matter of the past century. [3] I imagine the division of that multi-ethnic territory that was always a border society, its very name describing it as the limes et fringo of a country, by forces hostile to each other accelerated the creation of a Ukrainian identity as people identifying neither as Polish, Jewish, German or Russian were forced to define themselves. This is supported by the fact that a Polish census from 1931 found that in the Polesie region, which had similar ethnic composition but was entirely under Polish rule, 62% of the population described themselves as “locals” with no national identity while according to the same census such people were absent from Volhynia. [4] This supports the case that the introduction of borders into a frontier community invites the concept of nationality and also strains relations between ethnicities, which I believe related.

This is not to say that there were no ethnic tensions prior to the Versailles order. In 1908, after the murder of the Polish governor of Galicia, count Potocki by a Ukrainian nationalist, a Viennese newspaper wrote: “In Galicia the dangerously explosive masses of national dynamite lie stockpiled, so that the opposition between Poles and Ruthenians can not bear any further deepening or sharpening.” [5] Indeed the tension between Ruthenians and Poles had a long history, hailing back to the XVIth century, yet it was only during the XIXth century that the struggle transformed from class rivalry correlated with ethnicity to national antagonism, which again I think to be connected with the growing stratification of Ukrainian society, though it should be noted that it was mostly impoverished rural workers who supported the genocidal Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists in the ethnic cleansing of Poles, perhaps purely for economic reasons. [6]

While the Polish state enforced law within its borders, ethnic tensions could be contained by a combination of anti-terrorist measures and tolerant administration, yet the very existence of a Polish state stimulated Ukrainian self-identificaton. The situation could be well compared to that of contemporary Israel and Palestine, since in both cases a nation reclaims a territory it deems historically its own only to bring about the creation of a hostile nation from the countries contemporary inhabitants. With the demise of the Poland during the Second World War, in the words of Timothy Snyder: “Polish property-owners had no state to protect them, and Ukrainian peasants were organized by those who wished to build a state themselves” [7]. Genocide ensued.

[1] - Vladimir Temnitsky, Joseph Burachinsky, Polish atrocities in Ukrainian Galicia;

A telegraphic note to M. Georges Clemenceau, president of the peace conference,

(New York, 1919) p. 3-5

[2] - Miroslav Hroch, 'From National Movement to the Fully-formed Nation:

The Nation building Process in Europe', in: Mapping the Nation, ed. Gopal Balakrishan, (London, 1996), p. 80

[3] - Thomas Eriksen, Ethnicity & Nationalism; Anthropological perspectives,

(London 1993), p. 13-14

[4] - Piotr Cichoracki, 'Problem świadomości narodowej mieszkańców województwa poleskiego w okresie międzywojennym (1921-1939)- Oceny, kontrowersje, następstwa',

II Міжнародны Кангрэс даследчыкаў Беларусі, Працоўныя матэрыялы, No. 2, (2013), p. 137;

'Drugi powszechny spis ludności z dn. 9.XII 1931 r. Mieszkania i gospodarstwa domowe. Ludność. Stosunki zawodowe. Województwo Wołyńskie',

in: Statystyka Polski, No. C/87 (1938), p. 22

[5] - Neue Freie Presse, Vienna, 18 April 1908,

as quoted in: Larry Wolff, The idea of Galicia, (Stanford, 2010), p. 341

[6] - Alexander Motyl, 'The Rural Origins of the Communist and Nationalist Movements

in Wolyn Województwo, 1921-1933', Slavic Review, Vol. 37, No. 3 (September, 1978), p. 419

[7] - Timothy Snyder, 'The Causes of Ukrainian-Polish Ethnic Cleansing 1943',

Past & Present, No. 179 (May, 2003), p. 227