Is nostalgia resistence to official memory? Part 3.

Andrzej Wajda's 1976 Człowiek z Mamuru (Man of Marble, see above) is a film shot not only about time but in time. The story of a young film-maker who decides to do her dissertation on a mysteriously disappeared communist hero from the 50's and her subsequent problems with completing her project constitute a shockingly clear criticism of the lack of free expression in 70's Poland. The film explores the relationship between fact and official memory and the mode in which official narrative is created and preserved via institutional control over the creator. The protagonist decides to explore archival footage cut from the 'Polish Film Chronicle' and learns of a story edited out of the official narrative. When in the 1950's heroes were on demand, the film industry delivered and created them out of honest and hard working individuals. However, when these new symbols refused to be passive and attempted to change the world around them, even in accordance with socialist ideals, they had to be toppled and their marble statues locked up in a cellar. When over twenty years later a researcher disturbs the past and explores what was once official memory, they get shunned for digging up 'different times' and their inquiry is obstructed. Wajda presents early socialist Poland without nostalgia; the contrast between the depressing depiction of bulldozers knocking down fruit trees and hungry workers waiting in the mud for a sardine after a hard days work with the exalted voice of the narrator that declares the correct interpretation of what is seen, together with the fact that what is being discovered in the archives was never broadcast for 'technical reasons' presents a reality of dirt, chaos, poverty, propaganda and totalitarianism. While there is no trace of nostalgia for the 1950's among the film's characters, the official narrative has adapted and 'those times' are not only condemned to oblivion, but so is their propagandist depiction. What is presented as the 'Polish Film Chronicle' does not in fact qualify as a chronicle as it does not serve remembrance: what is presented by the state as official and objective material that will inform people of the future about past reality is in fact temporary propaganda that soon becomes uncomfortable.

Interestingly, after the fall of the political regime Man of Marble has become a site of nostalgia for the late 70's. The visually appealing shots of cars, roads and typical interiors, arguably what allowed the film to eventually pass censorship, made the film into a journey into the past that does not neglect to criticise the political system of both the 50's and 70's. What had been a refutation of official memory practice, a film that was a political statement against the times it depicted has since obtained a new usage. However, the nostalgic revisiting of the film has not lessened the anti–regime message: an organic and spontaneous nostalgia for a period does not have to be in conflict with a condemnation of the political situation at the time.

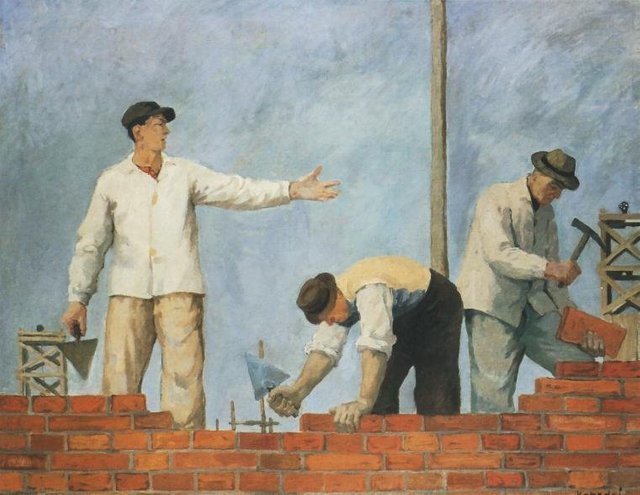

Polish socrealist painter Aleksander Kobzdej, 1950, Podaj cegłę (Pass the brick)