POETRY OF ARCHAIC GREECE 2 - Homer

Rage...

Don't forget to check out "Poetry of Archaic Greece 1" on the poet Hesiod for more by visiting the History community, or going to my personal blog page!

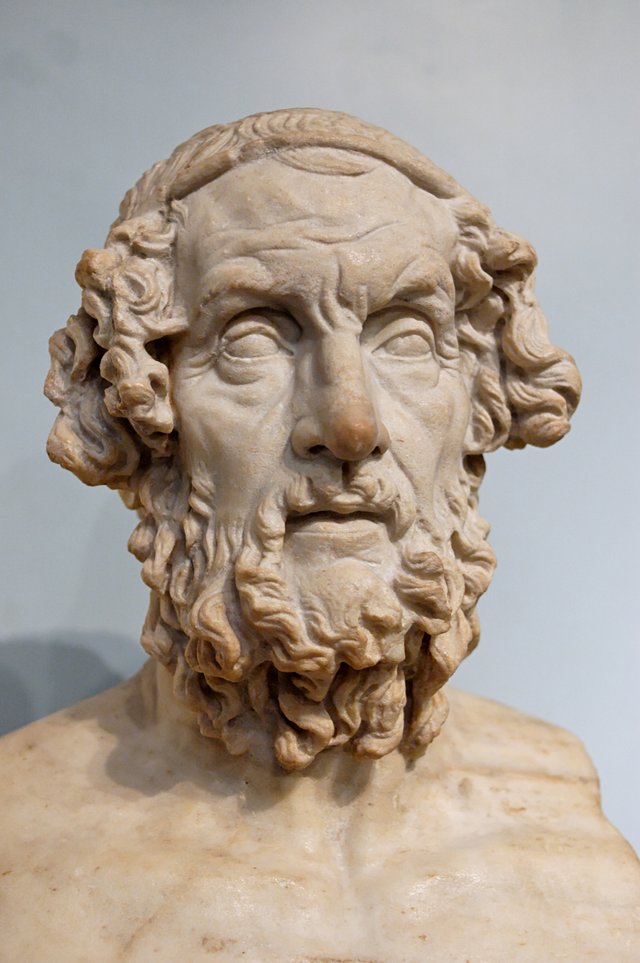

(ABOVE: Bust of Homer from Rome, 2nd century AD, based on a Hellenistic original)

Homer is the Greek-given name to the man famous for composing the Iliad and the Odyssey, two ancient Greek epic poems. The Iliad is set during the Greek war with Troy, a 10 year war which likely took place between 1194 and 1184 BC, with a primary focus on the conflicts between the Mycenaean Greeks and the Greek city-state of Troy in Troas. It also delves deep into the personal conflicts between the king of Mycenae, Agamemnon, and Achilles, a warrior fighting for his army. In part, the Odyssey is a sequel to the Iliad, following the king of Ithaca, Odysseus, and his 10 year journey back to Ithaca after the siege of Troy.

Accounts on Homer’s personal life have circulated throughout the ages. The most widespread speculation claims he was a blind bard from Ionia. Some modern historians and scholars regard these as legends and not accurate. The Homeric Question looks into the doubts and debates of Homer’s actual identity, as well as who actually wrote the two epics, and if they are accurate or not. Another question concerns whether the epics were composed by one man or many; “Homer” could in fact be best used as a label for a tradition of oralists of the time. While Homer was a poet and an oralist, he wasn’t a writer; his epics were composed entirely without the aid of writing. Given this fact, it’s even more impressive in knowing that the Iliad itself is some 15,000 lines long, and the Odyssey is a further 12,000 lines long. These roughly 27,000 lines of poetry being composed by one man suggest that this form of oral composition was at least a tradition, and the author(s) of the Iliad and Odyssey would have at least built upon this tradition. This theory is backed up by the fact that much earlier epics are known to have existed to us today, dating to even the Greek Dark Ages, however these poems themselves do not survive. So while Homer is not the oldest surviving author in western literature, and the Iliad is likely not the oldest epic ever written, it is still the oldest known to us today.

--

THE ILIAD

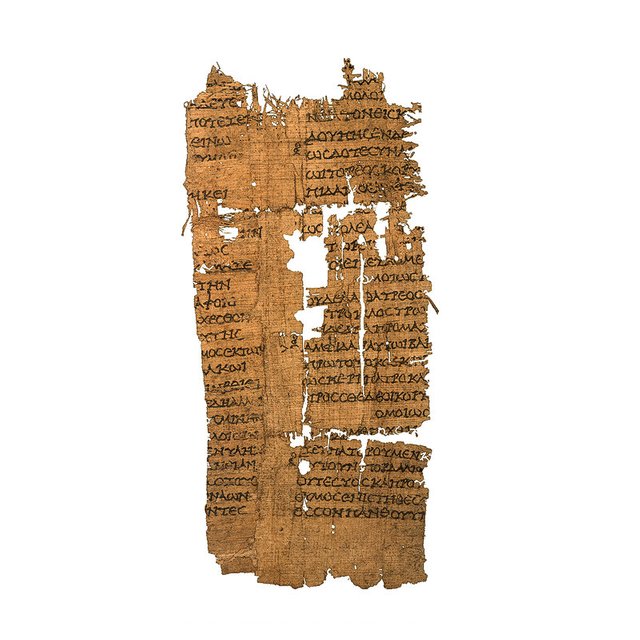

(ABOVE: "The Iliad" papyrus fragment, made up of 2 columns of 5 stanzas (group of lines) of Book 16 + 17, now part of the Oxyrhynchus collection, Global Egyptian Museum)

The Iliad was first written up around the end of the 8th century BC, likely between 720 and 700 BC or later. It’s known to us today as the earliest surviving piece of European literature, slightly predating the Odyssey, Homer’s other epic. Its sheer age and title of “oldest surviving European literature” alone gives the Iliad a spot in western literary canon, and goes a way towards explaining the authority with which it has been invested by generations and nations since.

(ABOVE: "Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus" by Nikolai Ge, 1855, now held in the Belarusian National Arts Museum, Minsk)

The Iliad (so-called after the local name of Troy: “Ilion”) is set during the Trojan War. Greek tradition tells us that this war lasted for 10 years, a time in which a Mycenaean Greek army lead an attack on Troy, besieging it and eventually destroying the city completely. Troy was supposedly located at Hissarlik in modern day north-western Turkey, and modern archaeology has revealed that an ancient settlement dated to the time period did indeed meet a violent end. It’s still not entirely known to us if the Trojan War even happened, but to the Greeks reading of it, it was an episode in their collective history as a people, and were familiar with the myths surrounding the war. The Iliad dictates that the war started after Helen, queen of Sparta and wife of the Spartan king Menelaus, was abducted by Paris, a prince of Troy, that Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, sailed to Troy for revenge, and that the Greeks built the Trojan Horse as a means to sneak into the city and capture it from within.

The Iliad itself though doesn’t focus on the entirety of the 10 year war, but instead focuses on about 50 days, and a selection of days of actual fighting; Even the first two lines of the Iliad make this clear: the epic follows Achilles’ anger, and even the first sentence of the Iliad is one word which describes this perfectly: “Rage.” Achilles first is angry over the arrogance and actions of Agamemnon, who takes away a girl given to Achilles as a battle prize. Then, Achilles refuses to fight, which results in the Greek army loosing morale, and loosing soldiers, which later comes to include Patroclus, Achilles’ lover, who is killed in combat by Hector, Paris’s brother and the other prince of Troy. Hector killing Achilles forces Achilles’ rage to unveil itself again, and he withdraws from isolation to face Hector in a duel, of which Achilles emerges victorious, dragging Hector’s corpse around the walls of Troy by a chariot. Taking Hector's body back with him to camp, Achilles is eventually approached in the night by Priam, king of Troy, who pleads the warrior to return his son's body to him, to which Achilles eventually agrees to.

(ABOVE: "The Wrath of Achilles" by Michel Drolling, 1819)

The Iliad’s action is focused primarily on the fighting. Epic clashes between armies make up the vast narrative of the epic’s story, and while warfares devastation upon humanity is a reoccurring theme, warfare as a means to allow both sides of the conflict to gain personal glory and honour, primarily by the characters killing each other, is also a reoccurring theme; battle scenes are ones that encompass the attention of those that are presented with the epic. The Iliad, and epics alike it, clearly focus on the heroes rather than the more everyday foot soldiers, presenting the focal characters as stronger, more attractive and braver than everyone else in such a mythologised past. As well as the human characters that appear in the Iliad, the deities that the Greeks worshipped also feature as characters; gods and goddesses like Apollo and Athena feature heavily in the narrative, playing key roles in tipping the scales of the war in favour of either side depending on the current narrative. Fate is also a key player in the Iliad, as both the listening audience and the heroes in the epic would all have known what fate ultimately awaited them during the war; Achilles set off from Greece knowing he wouldn’t return home, and knew he was destined to die at Troy.

(ABOVE: "Achilles Slays Hector" by Peter Paul Rubens, 1630-35)

--

THE WORLD OF THE ILIAD AND THE ODYSSEY

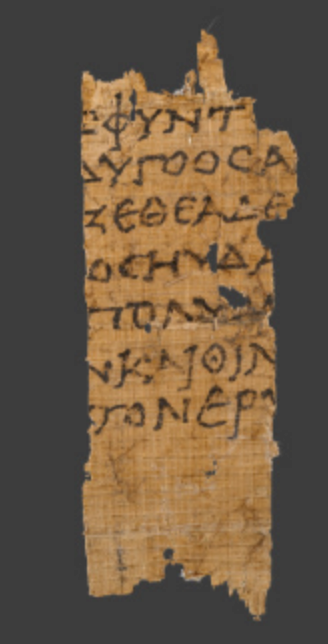

(ABOVE: Papyri fragment of The Odyssey from Egypt, 1st century BC, now at the Getty Museum)

Works and Days is set during a time of no war. The Iliad is not. Turning from Hesiod’s poem to Homers is equivalent of turning from reality to fantasy, and while Homer’s two epics weren’t as fantastical as perhaps other epics of the days were, the heavenly interventions in battles by the gods in The Iliad and the giant monsters present in The Odyssey definitely places Homer’s two works in the realm of fantasy, even if there is some truth to other events described in the poems. However, alike to Hesiod, Homer told his stories shaped by past poetic traditions; The Iliad and The Odyssey were retold with similar agendas of the time of Hesiod’s work, which were written at roughly similar times.

It might be tempting to take every description of objects, places and landmarks in the two poems as reality at some point. While everything in the poems, due to the fantastical elements of them, should definitely be up for debate as to whether they really existed or happened at all, it was these questions that lead Heinrich Schliemann to excavate Greece and western Turkey - the settings for the Mycenaean world in which the two epics take place - and discover Bronze Age remains now known at sites like Mycenae and Troy. These discoveries also told us that the items and locations described in the poems will have been mostly alien to Homer’s audience. These descriptions of old and foreign objects and places owe their being to the want to make up a lost, yet somewhat familiar, world to stimulate critical thought about the times of Homer’s audiences, alike to how the world of the golden race stimulated thoughts of the audiences own days in Hesiod’s Works and Days. Demands for context on a particular unfamiliar subject by the audience will have indirectly allowed that object or place to have remained intact for longer; The Boars Tusk Helmet, given by Meriones to Odysseus in The Iliad, might have survived for longer due to that particular chapter in The Iliad being an exceptional one, and wasn’t a scene relatable to any other part of an epic of the time. On the contrary, other objects originally described may have changed in their descriptions over time to meet the purpose of the day the play was being told in; Aias’s shield in The Iliad seems to have originally been a leather one, but was later changed to metal as shields in general became metal later on in Greek history, and even later acquired a central boss. These minor changes were done to meet the demands of the audience so they could better relate to and understand what was being described to them. Alternatively, descriptions of objects could have lost its purpose entirely should the object have been too unfamiliar to the original audience.

MARRIAGE IN THE ILIAD AND THE ODYSSEY

Marriage is a key part of The Iliad; The married king and queen of Sparta, Menelaus and Helen, are vital parts in the Trojan War, as it is Helen that was seduced and taken to Troy by Prince Paris. Networks of marriages across Greece and Troy formed alliances on both sides, escalating the war even further in scale. Marriage is also a central aspect of The Odyssey. Odysseus was from the island nation of Ithaka, and life in Ithaka during Odysseys’s travels to and from Troy has come to be focused primarily on possible suitors attempting to impress Odysseus’s wife, Penelope. The Odyssey ends with these men being killed by Odysseus, and the two being reunited.

Marriages amongst the elite are commonplace in both epics, and are described in lot of detail; Brides were often seen as a prize, bought by the bridegroom’s personal qualities and by his gifts to his new family. Other cases tell of the brides not being bought off, but rather giving expensive gifts to her new family; In The Iliad, the Lycian king proposes Bellerophon half his kingdom upon him marrying his daughter and settling in Lycia, and, also in The Iliad, king Priam of Troy, ever the polygamous character, wants to ransom his wife Laothoe’s children out of the resources that she had brought into her new family.

Within marriage in the epics, gifts commonly went from one family to another, but never vice-versa. No clear pattern of different bride and groom statuses seems to ever determine the pattern. The poems do, however, show signs of regarding a bride’s father’s gifts to the groom as something whose unusual nature can be taken advantage of in marking out an unusual social occurrence. For example, Agamemnon attempted to persuade Achilles to return to the fight is an offer of his own daughter without receiving any gifts from Achilles, but with treasure gifts TO Achilles. This does seem to point to the likelihood that social norms had come to be nailed into the epic tradition, and that an out-of-date custom was exploited, as it raised key questions about The Iliad’s plot.

POLITICS IN THE ILIAD AND THE ODYSSEY

In essence, The Iliad and The Odyssey are both political poems; large amounts of creating and enforcing of decisions by rulers, elite groups and the people are made, and where the fortunes of some communities, most notably Troy and Ithaka, are a more serious problem. Notably, the army camp established outside of Troy by the invading Greeks was politically structured too, and Odysseus’s visit to Phaiakia gives way to a chance to start exploring a political order and introducing it into a mythical landscape explored during Odysseus’s travels. Some rulers at times also show a large degree of powerlessness; not only does Agamemnon have no power in convincing Achilles to rejoin the fight in The Iliad, but he also cannot impose his same will upon his own army. Even Odysseus in The Odyssey achieves his final triumph in Ithaka by force instead of virtue. Individual people in both epics implement their political influence over other in accordance with where they stand socially, their rhetoric and their charisma, but not in accordance with their holding as ruler. A ruler’s role was to take care of their people, but the responsibilities of being a ruler come about most clearly when the rulers fail in successful rule. But it’s always unclear as to what a ruler was; Odysseus succeeded his father, Laertes, while he was still alive; Laertes seems to have had no major influence or roll in politics. On the contrary, Odysseus’s and Penelope’s son, Telemakhos, doesn’t inherit the position as ruler of Ithaka while Odysseus himself was absent. He wasn’t even guaranteed it should Odysseus have died. This regularity of uncertain power clarity and succession can also be observed through the ruler’s consorts; While Agamemnon was at Troy, Aigisthos took Clytemnestra, Agamemnon’s wife, as his own wife, taking power in Mycenae as the new King. It seemed a given that any suitor that married Penelope would acquire huge amounts of influence politically, but it’s just as clear that Penelope would be sent back to Ikarios (her father) as she had no real power constitutionally. In Phaiakia, the last destination reached by Odysseus in the Odyssey on his travels back to Ithaka, this sort of situation is replicated; the power of Alkinoos’ wife, Arete, is often emphasised, like when Odysseus is told by Nausikaa, her own daughter, that Odysseus must go to her first, as it was said that she could “resolve quarrels even among men”. Yet still, her position in the palace seems to have been solely a domestic one, and, compared to other rulers in both epics, Alkinoos acted more authoritatively when in Phaiakia.

It’s easy to observe why exactly rulers in these two poems were so vital. On the contrary though, it was the rulers that enabled the clashing of communal and personal values and responsibilities to be dramatically highlighted: personal decision-making could have had big political consequences, and political decisions could have had personal consequences too, but when this is applied to the rulers, what resulted from their personal decisions would have been dramatic and immediate. To contrast, personal and political decisions being intertwined was brought more so to a society where power wasn’t in the hands of one person, if the official powers of the ruler were to be removed from the picture. Sole rulers (monarchs) are good to think with in a society which lacks in them, especially so. It should be seen then that the rulers depicted in Homer’s epics weren’t kept about solely because they reflected the same rulers of Homer’s day, or even just because they showed off what kings of the past were like, but mainly because they were key parts in effectively exploring issues and topics that the poem wished to explore to entertain the audience members, as the tradition’s forefathers would have also desired to do.

WARFARE IN THE ILIAD

Warriors mounted on chariots is a notable feature, and chariot warfare was indeed very much prominent in the Bronze Age across the Mediterranean. The other prominent feature of The Iliad’s warfare is hero-on-hero fights, or duels, being of a heavy contrast with the huge armies who would fight on either side seen in the historical record. There is no ancient author who, to our current understanding, gave a concise historical view on organised warfare of the times described by Homer, and it’s impossible to gain such a view solely by reading up on The Iliad. Achilles close warrior followers, the Myrmidons, amass close together for a fight, but are mostly invisible once actual battle begins. Heroes face off against one another, and when one falls, other heroes step into their place to fight over their body. The most well known example of this is when Patrokles, Achilles’ lover, falls to Prince Hector’s blade during an assault on the Trojans, and the battle over his body ensues. To this, chariots make a common appearance, being at hand to transport the body, constantly roaming the battlefields as though there were no soldiers there. Items present in these scenes seem to belong to different ages, as already discussed, but this equipment was not inserted into a tactical framework which was consistent through The Iliad, and so it has little sense to it militarily speaking. This lacking in military sense tells us for certain that The Iliad’s image of warfare isn’t an accurate one for any given point in history, but it does provide a picture of certain key features of what it is to fight to be stressed, as well as who must fight; the role of individual duels alongside large-scale battles with thousands of soldiers are definitely brought out, and both of these are vital to the plot of The Iliad.

This all doesn’t mean that the descriptions given of the armies and the fights cannot be of interest to us. Just like how certain items can be proved to be existing memories from the past, so can, although perhaps non-provably, certain mentioned tactics (such as Achilles’ close-packed Myrmidons) can possibly be in reference to actual fight tactics at some point in history.

To conclude, The Iliad and The Odyssey do not give us an accurate picture of Greece or the Greek world at any one point in its history; poets would take from past traditions within their work to make poems that use the past to think about the present, and engage in it. Unrecognisable institutions and objects being included wasn’t done via blind line repetition made by earlier orators, but instead was the outcome of critical use of an inheritance to focus the listener’s attention onto their present concerns.

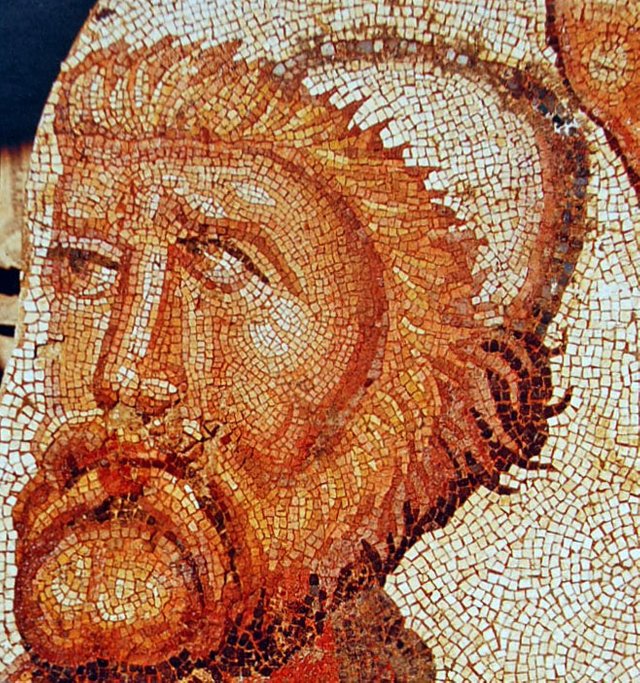

(ABOVE: Odysseus depicted on a mosaic from La Olmeda villa, Petrosa de la Vega, Spain, 4th-5th century AD)

--

EXAMPLE TEXTS FROM HOMER

[Iliad 14, 402-6]

“Glorious Hector hurled his spear at Aias at a moment when he was turned directly towards him, and he did not miss. He hit him where the two baldrics were stretched across his chest, one for his shield and one for his dagger with silver rivets. These protected the soft flesh. Hector was angry…”

[Odyssey, 11.435-53. Odysseus and Agamemnon on wives]

“So he spoke, and I replied and addressed him: “Alas, far-sounding Zeus made women from the beginning the instruments of his terrible hatred of the offspring of Atreus. Many of us perished because of Helen, and Clytemnestra arranged this trick for you when you were still far away.” So I spoke, and he replied and straight away addressed me: “So, you should never be easy with your wife. Don’t tell her the whole of what you know, but tell part and keep part concealed. But you will not be murdered by your wife, Odysseus: the daughter of Ikarios, shrewd Penelope, is very discreet and her mind knows clever ploys. She was a young bride when we left her behind and went to war, with an infant son at her breast who must now be counted among the men, happy he. His father will see him when he comes and he will embrace his father, as is right. But my wife did not allow me even to set eyes on my son before she murdered me.””

[Odyssey, 2.25-34. Speech of Aigyptios opening the assembly which Telemakhos has called]

“Hear what I say, men of Ithaka. Neither our assembly or our council has ever met since glorious Odysseus went off in the hollow ships. So which of the young men or the older men has had to call it now? Has he heard some news of an army invading - perhaps he could tell us clearly if he is the first to learn it? Or does he want to declare and tell some other public matter? He seems to be a good man if he will do us some good. May Zeus bring good to completion for him according to his heart's desires.”

[The Iliad, 17.262-8. The Trojans advanced to try and take the body of Patrocles]

“The Trojans pressed forward in a crowd, Hector leading. As when a great wave roars against the current at the estuary of a swollen river, and the heights of the shore boom around as the sea bellows out, such was the shout of the Trojans as they advanced. But the Akhaians stood around the son of Menoitios with a single resolve, walled in with bronze shields.”

--

SOURCES:

• Hesiod's "Theogony" and "Works and Days"

• "The Histories", Herodotus

• "Moralia", Plutarch

• "Texts, Readers and Writers" lectures, Prof. Eleanor Dickey

• "Ideas of Authority", Lynda Prescott and Fiona Richards

• "Early Greece", Oswyn Murray

• "Greece in the Making 1200 - 479 BC", Robin Osborne

--

YOUTUBE LINKS (I DO NOT own these videos)

Overly Sarcastic Productions

• "History-Makers: Homer"

• "What's the point of the Iliad? (or why book 24 is actually the climax)"

• "Classics Summarized: The Iliad"

• "Classics Summarized: The Odyssey"

--

If you're interested in reliving the epic of Homer's Iliad in game form:

Coming 2020

V. detailed post Harv!

Ta very much :)