The Lost Children of 1968

The Lost Children of 1968

Where The Wild Things Were

1968

In its quintessential form, the 1968 retrospective looks always exactly like this. Or this, from the New York Times. A multi-faceted shit storm of war, assassination, riots, sex, drugs, space exploration, expanded consciousness and art.

But, for those of us born into that shit storm, the heinous, but predictable, historical talking points remain a narrative that continues to isolate us.

To pinpoint it, I was born three weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr and three weeks before the assassination of Robert Kennedy. In World War II, Scrap Drives had families sacrificing their metal objects to help fight the war. In 1968, that sacrifice was attention.

1968 was a cataclysmic time. There’s similarities being drawn between then and now. But as similar as they are, they differ in one vast way — today we obsess over our children and in 1968 they were barely conscious of us. And so the cultural discussion of history, by its nature, leaves out the Lost Children of that time.

I’m part of a group of kids that aren’t called The Lost Children, only because of the very nature of being Lost Children — there was nobody interested in categorizing us. It happened individually — my sister referred to me, appropriately, as *Space Cadet. *And then she went off with her friends to go smoke pot.

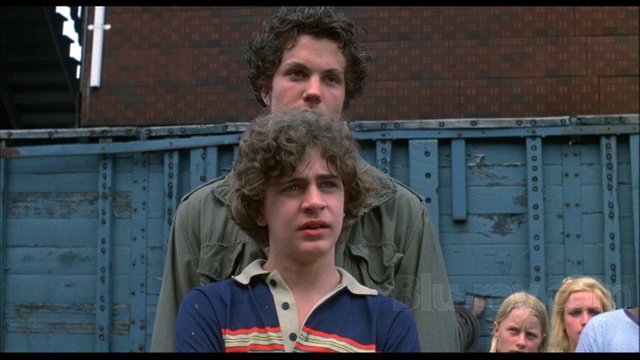

Despite this, you have seen us defined — as kids lacking definition. Movies like Parenthood, The Ice Storm, Almost Famous and My Bodyguard are only a few that feature realistic depictions — the list of metaphorical ones (like *E.T., Karate Kid *or Harold and Maude) is even greater. We meandered through the 70’s and into the 80’s alone and so completely overshadowed by the context of our surroundings, and the self-absorption inherent in it, that the only way to depict us was as individualized, lost sheep. Usually with a need for someone older to protect or understand us.

Patrick Fugit in “Almost Famous.” Toby Maguire in “The Ice Storm.” Joaquin Phoenix in “Parenthood.” Chris Makepeace in “My Bodyguard.”

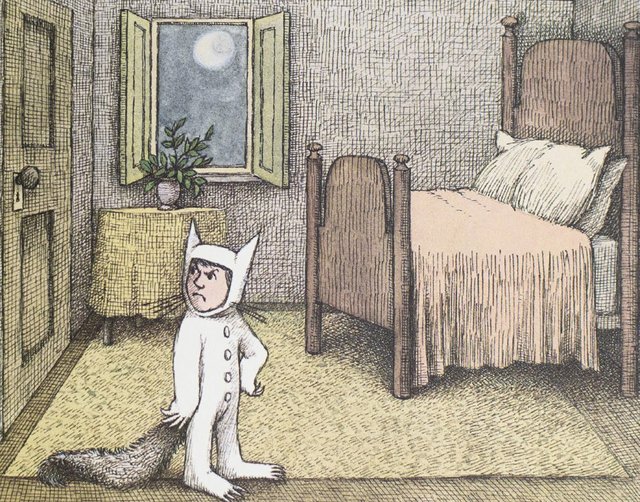

Frodo, Daniel-san, Eliot, Oblio and, of course, Max. You can’t even count how many 70’s cultural references key in on the theme of being lost — from Lost Boys to Land of the Lost. From H.R. Pufnstuf to The Point. From The Little Prince to Where The Wild Things Are. Even the Beatles movies, as fun-loving as they were, featured four guys running around, going nowhere.

We weren’t the first children depicted as lost, but unlike Mowgli or Tarzan of the generation before us, our jungle wasn’t apart from our day-to-day lives, it was our day-to-day lives. A naked, screaming, divorce court proceeding that played out in our own carpeted living rooms. Previously, a child returned from the land of wolves or the island of the Lord of the Flies. Here, he simply kept his head down and his guard up and got used to it.

I know we’ve come a long way,

We’re changing day to day,

But tell me, where do the children play?

So identity-less were we as kids that lack-of-identity is still how we are best-known. In the recent film, The Meyerowitz Stories, Adam Sandlar and Ben Stiller (both about 50 at the time of filming) co-star in a movie about two men competing over who is less comfortable in their own skin.

Still from The Meyerowitz Stories

Apparently, establishing an identity at my age is so hard, one must literally remove his own heart and rebuild himself from scratch.

Talkin’ Bout My Generation

You can’t completely disassociate this breed of Lost Children from Gen X, a group known for being “disaffected,” a state born of an environment of emotional abandonment. But if you contend, as I do, that we became disaffected specifically as a result of Baby Boomers’ obsession with rejecting traditional values, then it follows that 1968, where that cultural tension hit its highest note, resulted in the most disaffectedness. The most abandonedness. The most lostness.

But even the desire to situate my birthyear into a longer cultural timeline is a product of being born into it. We are, in fact, a group of people specifically trained in knowing the cultural surroundings and context through which things become what they become. Malcolm Gladwell, after all, is a Gen X’er, too. We are the writers, the observers, the journal-keepers and the photographers. Introverts and anxiety-prone. Not all of us, of course — but a high percentage, to be sure. My father’s 75th birthday and my son’s 15th birthday, when history looks back, will be oddly far bigger affairs, attended by far more people, than my 50th birthday party, which I’ll be perfectly happy to spend quietly in my home doing what I always do: being quietly in my home.

Gone To Vegas, Fend For Yourselves.

The truth is, almost nobody truly knows what it was like for us, except us. As much as it’s been attempted to depict in film and book, it’s actually far scarier than a Demagorgan. We weren’t disaffected, we were actually affected. And our stories are stuff of legends:

Somewhere around 8 years old on a Friday, I came home from school to a note from my mother that read,

Gone to Vegas, fend for yourselves.

xoxo, Mom.

I knew my mother well. I’d grown to understand the meaning behind the slightest of verbal pauses or steely looks. The hastily-written letter on the dining room table would have been the last-minute buttoning up of a quick exit to visit a boyfriend in the desert. A bit of fun and relief from a long work-week and the pressure of single-motherhood. I had an older sister, after all. She would have been 13. It would have been like One Day At A Time, if the kids were younger and Ms. Romano ran off on the weekends with Schneider.

Nothing dramatically bad happened on those weekends, by the way. Maybe one. But I did not run into Johnny, the Rogues, vampires or an extraterrestrial, though it all seemed plausible, because I was 8.

How big a help was my sister? Once on a bumpy airplane flight to visit our father, I got scared and asked her if the plane was going to crash. She replied, “It might.”

Sahara, Mirkwood and the Black Forest. I lived through them all.

The Walls

Being left alone is not the true damage of being a Lost Child. I liked being alone — and still do. The difficulty is in not being able to ever come back to reality. It’s in being trapped in your imagination and the inherent lack of context and explanation when things get weird. I grew up on comics, vinyl, Mattel and Coleco. It’s not enough. In fact, the walls of my youth that everyone felt protected me instead formed an impenetrable barrier to adulthood.

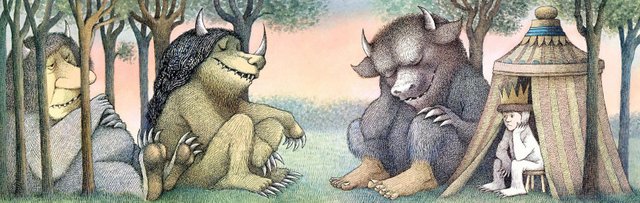

Max in his room. From “Where The Wild Things Are.” by Maurice Sendack

I could hear things going on outside my bedroom walls. Drugs being snorted, loud music, loud laughter, MAS*H episodes and sex. So much sex. The sounds of it would bounce back and forth from my sister’s room to my mother’s room and back. And sometimes simultaneously, like a competition between them.

I never came out from those walls. Long after mother died, sister was married and the house was sold off, the walls would remain. To such an extent that certain identity things continue to elude me. What it means to be a man, a father, a success.

The Hundred Year Flood

A “Hundred Year Flood” is a term used for a flood that produces a hundred years worth of water in one torrential season. It, obviously, has a very low chance of occuring, which is why it is also sometimes called the 1% flood. Such a flood happened in San Diego in 1980, when I was 12. We lived halfway up the street from a runoff of the dam at Lake Hodges, which we called the slough. It was the manifestation of all that is disgusting; bubbling with a viscous mass of smelly black sludge and still mosquito water. God help the poor soul who fell in, walking across the two-by-four makeshift bridge. It happened.

H.R. Puff n Stuff

That year, as the rains fell month-over-month, the slough became an ever-widening lake at the base of our street that slowly overtook basements, garages and bottom floors until, finally, one night, it reached us. In the early hours of the morning, with a few feet of water already creeping up my bedside, I slept. My mother and sister, however, had been up for hours, already moving items from the house and dealing with a different storm.

Of all nights, on this particular one, my sister’s boyfriend, Louie — who had been banned from the house — happened to have snuck in through her window. The predictable screaming over such a thing was superseded by the deus ex machina need for a helping hand and Louie ended up in the undesired role of man, carrying the large tube television set, boxes of books and albums up to higher ground. And all of this hullaballoo left my dog and me sleeping and stranded on a bed, with water rising quickly as the house’s treasures got marched out by a hungover interloper. I woke up to this and the sounds of our Scottish neighbor, screaming over the fence to turn off our electricity. I could only imagine what that meant.

Being a Lost Childis being born into a Hundred Year Flood. A 1% chance of cultural chaos that most children could never and will never experience again — even today, no matter how many comparisons are made. More things happened in a few short years to those born in ’68 than might to a century old man. The stories (mine and others) are endless. I drank kerosene, our curtains caught on fire, and my mom, sister and I all nearly died from chicken pox together — all before I was in grade school. There were movie directors, gamblers, pornographers, chefs, musicians, dealers and journeymen in our house on a regular basis. I could roll a joint, tell you the nicknames of any drug, read music, perfectly shade a sphere, develop film and read the racing form before I entered middle school.

And that’s the thing that’s so difficult to reconcile in the end. It’s wonderful, weird and terrifying.The same things that entrapped us in our stream-of-consciousness puppet worlds, also educated and enriched us. And nobody will ever understand how strange, evocative and lonely it was. Or likely even know where to begin to.

That’s what it’s like to be lost.

Sigmund and the Seamonster lunchpale. ©Sid and Marty Kroft