Race for 272 - General Elections in India: April – May 2019

General Elections in India is today probably one of the most eagerly observed and closely monitored events across the globe. And, the interest in it is not without any reasons. The reasons, however, are manifold. Stating the very obvious is the fact that India is the largest democracy of the world. With a population of 1.36 billion people, India constitutes 15% of the world population. The only country with a population larger than India is China, whose population stands at 1.42 billion. And it is widely expected that India will be the most populous country by 2030 overtaking China. Important though this dimension may be, the interest in India today is driven by many other factors some of which may assume more importance and significance than the mere size of the population.

India’s ‘Diversity’ is another dimension. In fact, diversity in India has so many facets that to understand it as a singular phenomenon and to call it a dimension would be a misnomer in itself. Religion (including variations thereof), Caste, Social Cultures, Language, Ethnicity, Region, etc. are all capable of being a dimension in itself. And they are in hundreds if not thousands.

Both the above-mentioned factors - Size of population and Diversity - are important dimensions. But they have been widely known for last more than seven decades in the context of India's general elections. So, while they both have a curiosity quotient, they are not the ones driving the interest today in India’s upcoming General elections.

India today is widely believed to be standing on the ‘Cusp’ of transiting into the realm of being a developed country. And what is even more widely believed is the fact that India today stands on this threshold due to the fast pace at which development has taken place in the last 4.5 years. All due to the towering personality and the vision of one man – India’s Prime Minister Mr. Narendra Modi. That the belief may come true is entirely possible. Pundits across the world are more or less in agreement over this possibility. India currently ranks number 6 worldwide in terms of GDP. It is expected to be at number 5 when the GDP figures are released by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in April 2019 for the current year. India is expected to overtake the UK which is currently no 5. The IMF also projects India to be $ 5 trillion economy by 2025. And by the year 2030, it is believed India will overtake Germany to become the number 4 economy of the world behind the USA, China, and Japan. Where does all this confidence come from?

India has invested heavily in infrastructure especially into regions which were hitherto left out. India’s growth story will no longer rest on the shoulders of India’s western corridors – states of Maharashtra, Gujarat – the traditional load bearers for India’s growth engine. The eastern and northeastern regions will also start firing on their cylinders propelling the growth story. These two regions have seen unprecedented levels of investments in infrastructure. The region – especially Northeastern – is being opened up like never before. Results have already started showing up.

Another important factor leading to confidence in India’s growth story is the fact that Modi has drafted the bottom half of the population to become participants in India’s growth through schemes like MUDRA Yojna. Hitherto these people used to be fed the staple diet of benefits and handouts. It prevented them from being a contributor to India’s growth and made them commonly give their votes in exchange for doles and freebies. One is not saying that the Modi government has done everything. There is still a lot of ground to be covered, diligently and assiduously. But the confidence of the pundits comes from seeing what has happened at ground level in the last 4.5 years and extrapolating on that experience going forward.

All of what has been said above is tremendously exciting. And is in the realm of distinct possibility. But whether or not it happens will depend upon the trajectory India takes going forward. Needless to mention that all these predictions are heavily dependent on one factor – whether or not Modi will return as Prime Minister post elections. In fact, this single factor will decide whether going forward India will be governed by policies towards growth and development. Or, it would slide back to the traditional dimensions of size, diversity – caste, religion, regionalism, etc. The upcoming General elections will decide that. And that my dear friends, is the singular most important dimension, why there is an unprecedented level of interest in India’s General Elections – ‘The Race to 272’ as we call it.

We have decided to get our readers an exhaustive analysis to help them understand the dynamics of this magnum opus called India's General elections. It will afford them an opportunity to appreciate the various pressure points operating therein. We would present a series of articles analyzing the situation state by state, or sometimes clustering some states together where the situation demands. Of course, it goes without saying we would base our analysis on hard data and facts. So take a ringside view for next month or so as we bring to you the analytical framework for India’s General Elections 2019.

Before we dive into the dynamics of the numbers on a statewise basis ad issues thereof it would be in order to understand some basics of how the whole electoral process works and how is the Prime Minister of India chosen. This will allow the readers, especially the uninitiated ones, to get a good comprehension of the articles that follow and to enjoy the analysis or perhaps even critique it and contribute to it also.

The electoral process in India works on the lines of the British system having inherited the same at the time of independence in 1947. The entire country is divided into 543 constituencies. Each constituency elects their representative and the elected person is called ‘Member of Parliament’ (MP). The congregation of the elected MP’s in the parliament is a house called Lok Sabha (meaning People’s House). The person securing more than 50% of votes from among the elected MPs (i.e. 50% or more votes in Lok Sabha) becomes the ‘Prime Minister’. This means a vote count of at least 272 MPs out of the Lok Sabha strength of 543 MPs. Hence the title of the article ‘Race for 272’.

The second question is how an MP is elected. Polls for electing an MP are held in each constituency. The candidate securing the maximum number of votes polled in a constituency is declared as the elected MP of that constituency. At this juncture, it is important that readers get to appreciate some finer nuances of the process.

First, there is no minimum or cut off, or base level. Technically even if one vote is cast the candidate getting that vote would be declared as duly elected.

Second, there is no limit on the number of people contesting in a constituency. It is fairly common to see the candidate list running into 20 plus candidates in a very large number of the constituencies. This has led to many dirty tricks evolving over time to subvert or thwart the electoral process that are legally correct but unfairly influence the electoral process. Many of the candidates stand for the contest knowing full well they have absolutely no chance of winning the election. But still, they stand. Reasons could be manifold. They hold a grudge against a particular candidate or a party. They, therefore, stand so that they can eat into the vote share and deny the targeted candidate a victory. Or this could be a way for them to get remunerated by some party who wants the opponents vote divided and thus reduced. This is when the revolting candidate comes from the same 'influence' group as the targeted candidate. This point is very well brought out if we study the data on the number of candidates forfeiting their deposits, which means they have polled less than 1/6th of the votes polled. In 2014 elections out of the total 8251 candidates who fought elections, a total of 7000 candidates forfeited their deposits. It works out to 84.8% of candidates forfeiting their deposits. Going back to 2009 elections this percentage was similar – 84.6% i.e. 6829 candidates forfeiting their deposits out of 8070. As a result of all this it is often found that the winning candidate actually musters extremely low voting percentage, but still gets elected simply because he is ahead of others who incidentally poll even lower votes. Needless o mention that the elected person may not really be a true representative of the constituency.

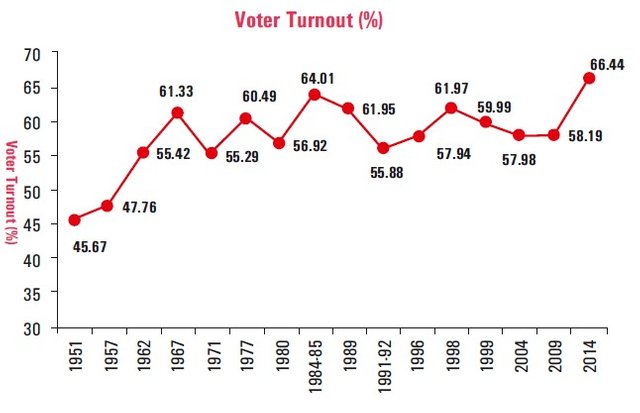

The third factor impacting the winner is the voting percentage and how the different influence groups vote. It has traditionally been found that India observed very low voting percentages (mostly less than 60). The graph below gives you voting percentages since 1951 – the beginning of the electoral process in India. One would observe that it was the highest ever in 2014 (66.44%). The closest to it was in 1984 – 85 which was an aberration of sorts. 31st October 1984, the then PM of India, Mrs. Indira Gandhi was assassinated. Since the elections followed closely on heels of the assassination, there was a huge voter turnout and it resulted in a landslide victory for her party. Bear in mind that in national level electoral politics even a one percentage point increase in overall voting can make a lot of difference to the electoral prospects of the different candidates. In 2014 we saw a huge – more than 8 percentage point – increase in voting (58.14 % to 66.44%). And the results were also similar. It was after almost 30 years (the last being in 1984 itself) that a party was coming to power with a full majority in India and it was not a coalition government.

Added to this low voting percentage is the fact that while the minority segments voting percentage is normally very high, that of the majority segment is normally very low. This not only gave a very distorted result, but it also cultivated a happy hunting ground for the political parties and candidate to play vote bank politics or politics of appeasement. A very simple data point establishes this fact. In 2009 a whopping 82% of winning candidates won even though they got less than 50% of the votes polled (448 out of 543 candidates won with their vote share being less than 50%). In 2014 this dimension i.e. people elected with less than 50% votes polled, saw a drastic improvement. It went down from 82% to 62%, a very significant improvement.

The fourth factor to be understood is the Dynasty system of almost all the political parties in India barring very few. In fact, barring the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP), the Janta Dal United (JDU) and the Communist Party of India - Marxist (CPM), all other parties are family dynasties. They fight the elections all right, but if they win, the head of the government is almost certain to be a member of the family. This was a clear indicator that India carried a feudal mindset – a legacy from the times even prior to British Raj. This was shattered for the first time in 2004 when BJP came to power as a ruling coalition and now in 2014 when BJP was voted to power with absolute majority.

Beyond the finer nuances of how the electoral process operates and is manipulated, there is the realm of fundamental election issues that have been found to be operating on minds of the electorate. Going back to 1969 when Indira Gandhi became the Prime Minister of India, the electoral message sharply swung towards being the messiah of poor. Banks were nationalized, Privy Purses were abolished (the ruling dynasties were abolished), Subsidies and benefits were doled out increasingly, appeasement of minority groups on basis of religion became the order of the day, and the caste politics became center stage. The last point became an even more important electoral manipulation point when Mr. V P Singh, the prime minister of India tabled a report in parliament for reservation for backward classes. In other words preferential treatment of backward classes.

A departure of sorts has been made to all this in 2014 when Modi fought the election with a message of ushering in development for all. This was eagerly lapped up by people who were disheartened and disappointed over the lack of growth (countries around India were making giant strides while India was getting left behind), favoritism, nepotism, corruption at massive scale, and the image and standing of India seeing a sharp downward slide in the international arena.

This election thus becomes critical for at stake is the whether people will slide back into traditional medicine of benefits, appeasements, corruption, nepotism etc. Or, will they bring back Modi based on their positive experiences and tangible results of last 4.5 years inclusive of all the trail, tribulations and hardships that the development process has brought.

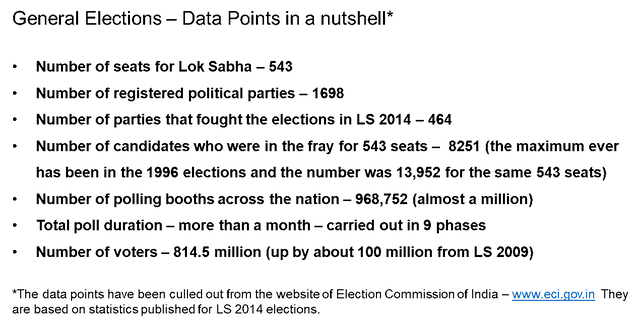

And this my friends is the reason for the extraordinary interest in India's Magnum Opus – Lok Sabha elections 2019. Stay tuned. Here are some interesting data points, in a nutshell, to enable the reader to get the magnanimity of LS Elections in India.

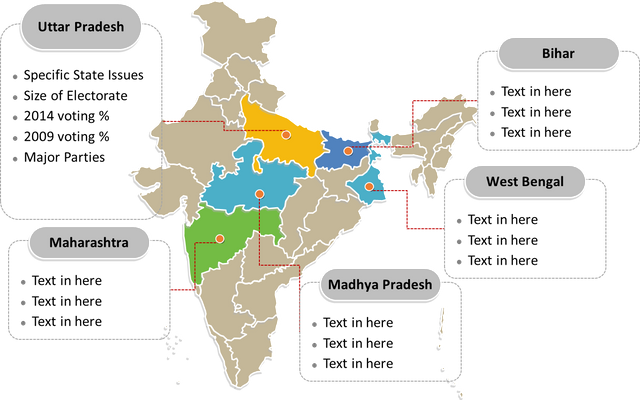

From the next article onwards we get into detailed individual statewise analysis including our assessments on total number seats. Our methodology for presenting you the detailed data and analysis is presented below.

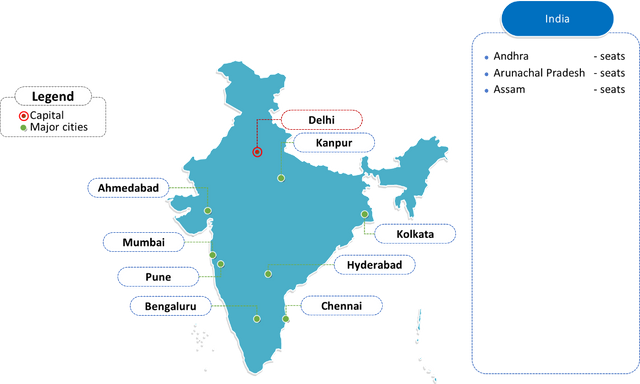

Our attempt will be to give you three baseline graphics with every article analyzing a particular state / s (we will club more than one state into an article where the number of seats is less than 10 or 15). These three graphics will provide the overall picture of the state. And these graphics will be in addition to the graphics we will use for presenting specific data and analysis. The sample for the three graphics are as below:

Graphic one – Overall seat position for the state

Graphic two – State on the Map of India

Graphic three – Running total

True that India's election is most complex one. Voting pattern is more about emotional appeal.