David Cameron's Great-Great Grandfather Alexander Geddes and the Great Chicago Fire of 1871

Alexander Geddes' Safe - The Great Chicago Fire - Private Networks - Intense Competition in the Insurance Industry - Reputed Fortune In Grain

"Without a complete understanding of economics history is impossible to understand." -- Ezra Pound

This is an informal forensic economic analysis of the events surrounding the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 based on the discussions of Hawks Cafe, Captain Sherlock and the Abel Danger virtual team of forensic economists.

After the great Chicago Fire in 1871, a Mr. Harris did a booming business in Chicago when Chicagoan's learned just to what extent personal belongings and important financial documents had been destroyed in the fire. It would seem people living in Chicago at the time, never thought about the consequences of losing all their valuables and important documents in a fire as destructive as the fire was in Chicago that completely destroyed four square miles within a twenty-four hour period between the night of October 8th and 9th of 1871.

Returning to his native Scotland in the 1880s, Alexander Geddes built the house of his dreams called Blairmore House with the date stone of 1885 bearing his initials. Among the mementos to be found in the Blairmore House, is a plaque from the safe which literally saved Geddes' fortune in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. What this informal forensic inquiry would like to discuss, among other important findings, are what exactly did the safe contain if not insurance contracts on put options on grains worth millions? The only treasure missing - sadly - was a safe that had been brought back from America and installed in the house by Geddes in the Blairmore House.

Blairmore House, the school's premises, is a Victorian mansion set amid 50 acres (200,000 m2) of woodland beside the River Deveron. It is 6 miles (9.7 km) from Huntly, 40 miles (64 km) from Aberdeen and 60 miles (97 km) from Inverness. The house was designed by architect Alexander Marshall Mackenzie and was built as a private home in 1884 for Alexander Geddes, a wealthy businessman and great-great grandfather of UK Prime Minister and Tory party leader David Cameron. Cameron's father, Ian Donald Cameron, was born in the house in 1932. Geddes made his fortune in Chicago in the US in the trading of grain in the 1850s, and a safe belonging to him which survived the Great Fire of Chicago was installed in the house's Billiard Room.

The safe apparently fell through the floor in in a fire in the 1970s and was sold for scrap - though a brass plate remains, with an inscription to the effect that it had survived the Great Fire of Chicago of 1871, along with Geddes's worldly wealth. "Had it not been for this safe, I would have gone bankrupt," reads the plate.

Blairmore House (School)- built for Alexender Geddes in 1884 beside the River Deveron

Alexander Geddes is the great-great grandfather of David Cameron who had made a fortune in the grain business in Chicago and had returned to Scotland in the 1880s. In one write up on Alexander Geddes, it mentioned that Geddes is "reputed to have made his fortune in the U.S." When a study is made of this history it is important to always look at anomalies, for example, there is absolutely nothing that can be found as to how exactly Alexander Geddes "made his fortune in grain" while in Chicago. Did he plant grain seed and sell the produce? Did he own storage facilities for grain? Or did he buy and sell grain as options? From the historical record, it appears that Alexander Geddes made his fortune on 'puts' and 'options' on grain deals. After the fire in Chicago in 1871, Geddes probably saw his fortune increase beyond his wildest imagination when hundreds of thousands of bushels of grain in storage went up in acrid smelling smoke the night of October 8, 1871.

Did Alexander Geddes buy his safe from a Mr. Harris?

Speculation: The above image is a S.H. Harris Co. of Chicago safe built around the late 1800s. Is this a safe similar to the safe Alexander Geddes owned while in Chicago? First a little history: The first American insurers modeled themselves after British marine and fire insurers. These American insurers were already well-established by the 18th century and it was essentially an unregulated market. American insurers modeled their insurance underwriting on Edward Lloyd's Coffee-house.

These American insurance companies which modeled their operations on Lloyd's of London were organized as joint-stock insurance companies, which raise capital through the sale of shares and distribute dividends, rose to prominence in American fire and marine insurance after the War of Independence. While only a few British insurers were granted the royal charters that allowed them to sell stock and to claim limited liability, insurers in the young United States found it relatively easy to obtain charters from state legislatures eager to promote a domestic insurance industry. As this agency system grew, so too did competition. By the 1860s, national fire insurance firms simultaneously competed in hundreds of local markets including in Chicago. Low capitalization requirements and the widespread adoption of general incorporation laws provided for easy entry into the insurance industry. At the time of the Chicago fire in 1871, there were 159 insurance companies operating in Chicago out of approximately 413 insurance companies operating in the United States.

One of the first insurance agents in Chicago was Gurdon Hubbard, a fur trader, investor, and speculator who arrived in Chicago from Vermont in 1818. What is fascinating is he was indentured to John Jacob Astor's (considered to be the wealthiest person in the United States at that time - his great-great grandson, John Jacob Astor IV, died on the RMS Titanic) American Fur Company for five years at $120 per year in 1818.

In 1834, Hubbard became the Chicago agent for the Aetna Insurance Company of Hartford, Connecticut, and this successful venture made him one of Chicago's most prominent mid-century businessmen. The Illinois Insurance Company, chartered in 1839, was the first insurance company to operate out of Chicago. The 1850s and '60s were a period of growth for Chicago insurance, as more national companies opened Midwestern offices and more Chicago-based firms were founded. Gurdon Hubbard sold his property and other assets to pay off insurance claims on his company to victims of the Chicago fire. Both the Aetna and Hartford Insurance companies first began in Hartford, Connecticut.

Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard - Aetna Insurance Company - the first insurance policy written in Chicago - bought Chicago's first fire engine - his 800 page manuscript was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire

The Chicago fire rocked the insurance world with the revelation that the industry was unprepared to meet such a massive calamity. The destruction was enormous wiping out four square miles of commercial property including buildings. Of the 129 insurance companies in Chicago, 58 went bankrupt unable to pay on insured claims. With close to 18,000 buildings burned, including 1,500 "substantial business structures," 100,000 people were left homeless, nearly 300 people were killed and thousands were left without jobs. Insurance losses totaled roughly $200 million which was a huge amount of money in 1871. The losses on many insurance companies exceeded their available assets and were forced into bankruptcy.

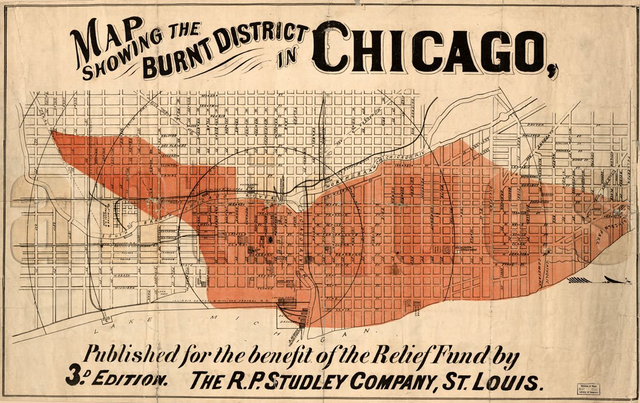

Dark shaded area indicates path of fire (Section 1 of map)

For the study of the built environment in Chicago, the fire insurance company atlases of the later 19th and early 20th centuries often provide the easiest access to the largest amount of information to assist insurance agents. Created to help insurance agents judge the risk involved in insuring properties of many different types, they give a wealth of excellent material information about the location of buildings, their footprint, the materials used in construction and building configuration.

In this reevaluation of the Chicago fire based upon recent discovery and examining the anomalies, the thought that the Chicago fire was arson set off to destroy competing insurance companies cannot be dismissed. Out of 129 insurance companies in Chicago, with 14 local insurance companies, 58 insurance companies were driven into bankruptcy not being able to pay out on claims. After the Chicago, fire the insurance business boomed in Chicago (Chicago and the Great Conflagration, page 346).

As has been pointed out insurance companies used the Lloyd's of London model in setting up insurance companies in the United States as well as modeling fire fighting on the basis of a company called Hand in Hand, which was incorporated in Britain in 1696. Hand in Hand was later purchased by Commercial Union and then later it became AVIVA. Hand in Hand had its own fire brigade, probably at the time a horse pulling a carriage of fire fighting equipment with some hammers and buckets, and these fire fighters in uniforms with badges and people were paying premiums to this insurance outfit Hand in Hand. If there was a fire, Hand in Hand firefighters would gallop out with their horse drawn carriages and try and put out the fire. Also, a study of the financial records available, revealed that Hand in Hand insurance company did not loose any assets resulting from the Chicago fire.

Hand in Hand Fire Insurance Society - founded in 1696

Looking at this history, if you were paying premiums to Hand in Hand and if there was a fire, Hand in Hand fire fighters would gallop off to a fire and try and put out the fire. At the time of the Great Chicago Fire, insurance companies formed private brigades of fire fighters to protect their clients assets. These private fire fighters would only fight fires at buildings that were insured. These buildings were identified by fire insurance marks. The image above is the mark the Hand in Hand Insurance Company used in Chicago on property insured by them. Now, if your neighbor's house and barn were burning down, and let's say for example the barn was insured with a competitor of Hand in Hand's, you can see that there is a strong interest for Hand in Hand to not help put out your neighbor's fire, in fact, maybe even help in burning it down, or just let the house and barn burn down. Because then, the person who has been burnt out next door to you, if claims are put forward to their insurance company, that insurance company goes bankrupt and your competitor disappears, and then you can say to the people whose houses burned down: "You see, you were insuring yourselves with the wrong people because they didn’t have enough money to compensate you."

When the smoke cleared that person would probably insure with this insurance firm with their assets still being in place. And this is precisely what happened in Chicago. Analyzing this carefully for anomalies, a process can be uncovered that gradually narrows the premium income in a town or area, to a city like Chicago in 1871 where 58 insurance companies went bankrupt. Some companies, and this is why its important to look at this as a type of insurance insider conspiracy, flourished. Although we're not discussing "conspiracy" so much as forensic economics, there is a Latin phrase, cui bono, which means who benefited? So what we want to do is look at the insurance companies that survived from 1688 onward that are now among the biggest insurance companies in the world, and compare their fate with the insurance companies that went bankrupt after the fire in Chicago in 1871. Do we see the hand of this organization now called 'SCRAP Merchant' all over Chicago in 1871?

Commercial Union which was previously Hand in Hand Insurance Company, established their insurance business in the United States in 1861. During the Chicago fire, Commercial Union had gross assets as of January 1, 1871 of $4,000,000 and cash capital worth $1,250,000, one of the biggest insurers in the United States. Commercial Union lost $65,000 in the Chicago fire.

Hand in Hand Insurance Companies was registered in Pennsylvania, and although this insurance company was an insurer in Chicago at the time of the fire, there is no financial record available. At the time of the Chicago fire, there were 413 insurance companies operating in the United States and of that number, there were 6 foreign insurance companies. After the Chicago fire, 58 companies were suspended due to bankruptcy, 28 companies had no insurance assessment against them and 135 weren't selling insurance in the Chicago area. One-hundred and twenty-nine American insurance companies were in Chicago with one foreign insurance company and that company was Commercial Union. Commercial Union is one of the largest insurers out of London and later bought Hand in Hand Insurance Company in 1905.

Joseph Leiter, the son of Levi Leiter [Field & Leiter], appeared to have "commission men" working for Alexander Geddes Co. in Chicago. This would also mean, these "commission men" built "intelligence networks" on what would be profitable in the insurance business and grain business. One of Joseph Leiter's profitable ventures was the production of coke, a component used in steel manufacturing. However, in order to produce this commodity - a rich supply of high grade coal, in large quantities, was needed.

CHICAGO, Dec. 28, 1879 -- Joseph Leiter [son of Levi] apparently has won a victory in his fight with George A. Seaverns, the grain elevator owner, as to the quality of wheat to be delivered on Leiter's contracts. Leiter's commission men, Alexander Geddes Co., sent the steamer Iron King last week to Seaverns's elevator, the Alton, to load with No. 2 red Winter wheat.

Marshall Field (Field & Lieter Department Store of Chicago)

Levi Zeiglar Lieter (Field & Lieter Department Store of Chicago)

Marshall Field along with Levi Leiter partnered and sold dry goods through their store called Field & Leiter. For many years Field & Leiter was Chicago's premier department store. When the fire destroyed their store, 40 percent was paid out in insurance and about three-quarters of the insurance stock was insured. In total, there were about $10 million in losses for all dry goods retailers in Chicago's commercial district where the fire burned.

Alexander Geddes made his fortune in the grain business in Chicago. His agents, called "commission men" (almost like Lloyd's of London's agents and brokers) were dealing with the Board of Trade in Chicago heavily invested in 'puts', 'options' and 'calls' - the Chicago fire made them a fortune. A London School of Economics idea? Imagine if you took out a 'put' option on coal alone; 160,000 tons went up in smoke in the fire. One-quarter of all grain storage, receiving and shipping was destroyed in the fire, e.g. flour; wheat; corn; oats, rye; barley. Receipts for corn delivery alone expected to be delivered on Nov. 11, 1871 were 817,905 bushels. What is astounding to discover is that if Alexander Geddes made such a fortune in Chicago in the grain market, which there is no doubt he did, there is actually very little historical record of him doing so, and how exactly he made this fortune. It is simply written off to history as being a "successful business man".

When reading history it is best to read books a close as possible to the dates being discussed; because they offer bits of exceedingly important economic forensics. In the book Chicago and the Great Conflagration on page 6, competition between insurance companies in Chicago was intense although described differently. Speculation, but it kind of makes one wonder that Alexander Geddes bet on the right side of the fire. After the Chicago fire, this had a pronounced effect on the entire insurance industry in regard to insurance rates. Again conjecture, but what better way to do that than a fire that consumed four square miles in 24 hours? People holding stock in these insurance companies were wiped out totally. In this same book on page 377, there was a warning given from the Tribune Newspaper: "Let this be lesson to only hold insurance with tried and true companies."

What is revealing is that it seemed a few in Chicago took out insurance weeks before the conflagration. A Mr. Pratt, who owned a coal yard in Chicago, insured his coal yard for $45,000. Odd because at that time coal yard owners never insured their coal yards. This indicates business owners were contacted by insurance companies prior to the fire as competing insurance companies looked for business. How easy would it be to sell insurance policies for potential disaster including fire, then torch Chicago in which 4 square miles were burned? This would have bankrupted insurers not prepared to pay out large amounts on losses. Mr. Pratt was the only coal dealer in the city insured. Did he get tipped off or is this just one of those odd coincidences?

If you read excerpts from the Police and Fire Commission (sort of like the 9/11 commission) inquiry of the Chicago fire, there is confusion and too many inconsistencies to simply dismiss as pertaining to a detailed forensic analysis. The inquiry revealed that there was conflicting testimony about what fire company showed up first around the O'Leary barn and vicinity to start extinguishing flames. Many fire departments vied with each other just like politicians do today for asserting they are number one. Human psychology would predict this to be a very accurate assessment of people whose behavior hasn't changed in hundreds of years. And further, if the Hand in Hand firefighting technique is considered, including animosities the Irish had because most firemen in Chicago at that time just as in New York on 9/11, were Irish. After the British-caused potato famine in Ireland, which was caused to force the Irish out of Ireland into America to build its infrastructure, it comes as no surprise prejudices and animosity were present.

There is a fascinating description of individual firemen who were called in as witnesses in the follow-up inquiry worth reading to determine whether or not they were influenced in regard as to what buildings would be protected. For some reason, this testimony in the book uncovered to read about this testimony have been deleted from the online book. One anomaly discovered was the following:

Mathias Schafer was the fire department watchman stationed in the cupola in the courthouse tower. His job was to scan the city for fires; upon sighting one, he would, via a voice tube, give the location of the fire to a telegraph operator in the third floor central fire alarm telegraph office. The operator would then strike the appropriate fire alarm box, which would ring the courthouse bell and bells in the various fire department company houses located throughout the city. On the evening of October 8 Schafer noticed a light in the southwest. He called down to William J. Brown, the night operator, and told him to strike box 342, which was located on the corner of Canalport Avenue and Halsted Street, about one mile southwest of the O'Leary barn. Immediately thereafter, as Schafer examined the growing blaze from his location in the courthouse tower, he realized that he had made a mistake. He called back down to Brown and asked him to strike box 319, which was located at Johnson and Twelfth streets, closer to the fire, but still seven and one-half blocks away. Brown, though, refused to do so, stating that he "could not alter it now." He believed that since box 342 was in the line of the fire, the approaching firemen would see the flames anyway, and he did not want to confuse the firemen by striking a different alarm box. As a result, engine companies that would otherwise have immediately answered the alarm were delayed. Many of the firemen later maintained that had the alarm been given correctly, the fire could have been extinguished relatively quickly.

The question then becomes, why did Mathias Schaefer pull the fire box 342 instead of the correct fire box 319? Could be nothing; could be everything. At this point it is difficult to ascertain. William J. Brown may have seen the fire as much as one-half hour before Schaefer called down to him. Brown, however, inexplicably failed to sound the alarm, choosing instead to wait for Schaefer to confirm the fire's existence. This also caused a delay in the fire department's arrival at the scene of the fire.

DeKoven Street is a street in Chicago named for John DeKoven, one of the founders of the Northern Trust Company. Mrs. O'Leary's barn was on DeKoven Street. State Street where the Field & Lieter; Leiter store was located and DeKoven Street (O'Leary's barn) are relatively close. From a rough calculation on a map of Chicago approximately 3,756 feet directly east. O'Leary's barn story (think of O'Leary's cow as the predecessor to Al Qeada) is exactly that, a story. To date, there has been no conclusive evidence put forward to prove exactly where the fire originated. Now, where was Alexander Geddes' office, is this where his safe was and where was he during the fire?

It is not astonishing to learn the number of fires during the eighteen-hundreds were in the hundreds in Chicago. Yes, frequent fires happened especially since open flames and wooden structures were predominant during this period of time in Chicago. Considering there were all wooden structures, this made for some rather intense flames. Now compare the stats of those fires during the 1800s to today's aircraft crashes, yes, airplanes crash but how many were caused to crash? If there was a raging fire and you were a firemen, your priority would be to extinguish flames first on assets that were protected by insurance, while non-insured assets would end up burning down. Or just the opposite, allow an insured asset to burn to collect the insurance.

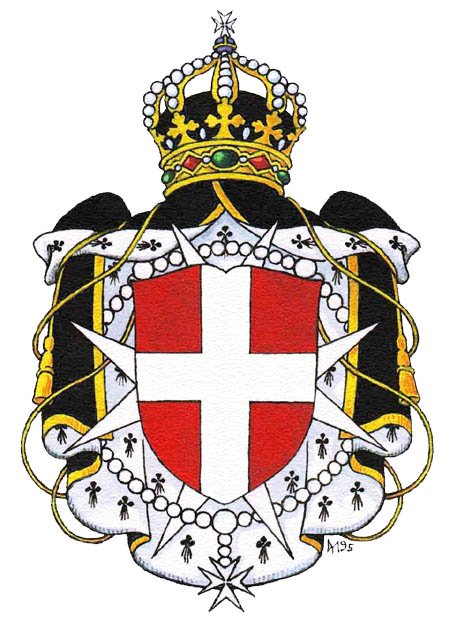

Ironically, the Chicago Fire Academy now stands on the O'Leary property on DeKoven Street. On the first floor of this academy, down a hallway, a Maltese cross is painted on the floor. The territory of firemen. The Maltese cross is the symbol of SMOM.

Sovereign Military Order of Malta

Another irony, the company Alexander Gedde Co. later went on to merge with another company and they came up with a component for fire extinguishers using licorice. Two Scots, Edward MacAndrew and William Forbes, traveled to Turkey in 1850, where they established the firm of MacAndrew & Forbes. Within a short time they built a licorice-extracting factory in Sochia. In 1870 James C. MacAndrew, David Forbes, and Alexander Geddes established an American firm by the same name in Newark, New Jersey, where they built another such factory.

It would seem Northwestern out did the University of Chicago:

The University of Chicago was founded by both Field and New York's John D. Rockefeller, to rival nearby Evanston's Northwestern University.

Hi! I am a content-detection robot. This post is to help manual curators; I have NOT flagged you.

Here is similar content:

http://netteandme.blogspot.co.uk/2014/09/alexander-geddes-great-chicago-fire.html

NOTE: I cannot tell if you are the author, so ensure you have proper verification in your post (or in a reply to me), for humans to check!

im upvoting but im going to have to read in the am because the first two paragraphs kinda make me feel dumb, like I won't understand what i'm going to read. I did peruse other paragraphs so I don't believe this will be the case. Blessed Be

Nice @tcwest

Shot you an Upvote :)

Keep up the great work @tcwest

Upvoted

Upvoted

Upvoted

Upvoted

Nice @tcwest

Shot you an Upvote :)

Hi! This post has a Flesch-Kincaid grade level of 11.3 and reading ease of 60%. This puts the writing level on par with Michael Crichton and Mitt Romney.