The Ultimate Reason Real Estate in Australia is So Expensive

Most Australians believe that homes are the ultimate, rock-solid investment. We’ve had 25 straight years of economic growth here in Australia, so many people assume we are a recession-proof culture and that homes will never go down in value, at least not significantly. They believe that current, insane home prices are fully justified.

About 15 months ago, I wrote an article on PropertyInvesting.com on this topic of why Aussie real estate is so expensive. It was one of the most read posts on the site for the year and quite a few people commented or asked questions. There were even some who vehemently disagreed with my conclusions, which is always fun.

I thought it was about time to update that article and post it here on Steemit.

In my last Steemit post, I wrote about the power of conformity or herd behaviour amongst investors and homebuyers in Australia. It’s a mindset characterized by the lack of individual or analytical decision-making. People make investing decisions based on what they see or hear about what other people are doing.

The Lunacy of the Aussie Real Estate Market Today

Home prices in Melbourne and Sydney have increased by over 40 percent in the last three years alone. We’re now in the spring selling season, and because of last year’s boiling hot market, many people sold their homes at the end of 2015 to take advantage of high prices. Much of this year’s supply, people who would be selling now, was pulled forward. They sold last year, so we have a shortage of listings this year.

Because of very low interest rates, demand is also being pulled forward from the future. People who wouldn’t be able to afford to buy a home until perhaps 2018 or 2019 are able to buy today. Demand is high and supply is low, so even after the boom of the last few years, real estate prices continue rising.

Here are two of the more noteworthy sales of the last month or so:

51 Rowland Street in Kew, a Melbourne suburb, sold for $4.8 million. That was a whopping $1.7 million over the vendor’s reserve price. What’s crazy is that the buyer bought it for the land only, which is less than a quarter acre. He’s planning to knock the house down and rebuild.

11 Lucretia Avenue, in the Sydney suburb of Longueville, sold for $1.175 million over reserve. The buyer paid $4.925 million, but at least he got a nice house with a pool.

I commonly hear of properties selling every week at auction for $200,000 or $300,000 over reserve. Multiple bidders show up and drive the price up far beyond the seller’s expectation in desperation to buy something. Many have been unsuccessful for months having been outbid by other buyers, so they are desperate to buy and end up paying crazy prices.

Here's another scary trend: More and more first homebuyers are now opting for risky interest-only mortgages. Unable to afford to pay down the principal, these unwise borrowers are speculating on two key assumptions:

My home will be worth more in the future.

My income will continue to increase, so I can pay the loan down in the future.

Interest rates will remain low.

This reminds me of an ancient Hebrew proverb…

“Pride comes before destruction, and an arrogant spirit before a fall.”

So what is ultimately at the root of this insane market behaviour?

Real estate is so expensive in Australia for the same reasons real estate has become very expensive in other areas of the world: the fractional reserve banking system, and more specifically over the past three years, the availability of cheap credit.

The Fractional-Reserve Banking System

For at least a hundred years, governments around the world have been attempting to grow their economies by encouraging debt. Not only are governments borrowing big, our current world banking system has also enabled average people to seek prosperity – or at least the appearance thereof – through debt.

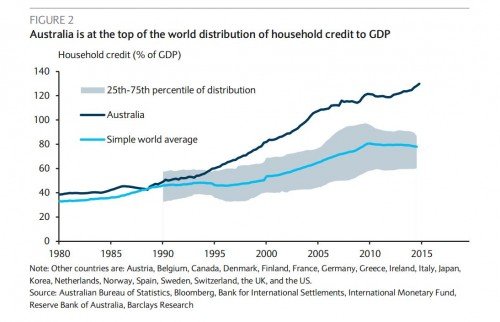

As you can see in the chart below, personal debt in Australia has risen dramatically over the past 30 years:

This growth in our culture’s love for debt has meant huge profits for banks. Banks primarily make money by receiving deposits, then loaning that money out to individuals and companies for a fee, called interest. What’s interesting, however, no pun intended, is that governments allow banks to loan out more than they take in through deposits; a whole lot more.

This system originally began in Europe hundreds of year ago. It’s called fractional-reserve banking, because the cash the bank keeps on hand is only a fraction of what it loans out. Banks are only required to maintain whatever amount they need to manage daily transactions by depositors.

It’s then up to the government regulators to act as the moral compass of the banking industry and enforce the reserve requirement, a limit on what fraction of a bank’s assets must be kept in cash. In many countries, that's the central bank's job. In Australia, we have a separate agency called Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, or APRA. It supposedly keeps the bankers honest, but it can indirectly use capital controls as a tool to either increase or decrease the money supply.

Large banks may be expected to maintain 10 percent reserves. Smaller banks may be given greater latitude at three percent or less. At present, required reserve ratios in most countries are no more than five percent.

In Australia, the liquid reserves to bank assets ratio was last measured in 2014 by the World Bank at 1.06 percent. That means the typical bank in Australia only holds about 1 percent of your deposits in cash. The other 99 percent has been loaned out to homeowners, investors, and businesses. Just in case you’re unsure how to feel about that, if you keep cash in Australian banks, it should make you very afraid.

The fractional reserve system works most of the time because rarely do all depositors demand their cash at the same time. But if depositors lose faith in the system, and all at once come to get their cash out of the bank, the foundation-less building will collapse.

Then, if the bank’s debtors are ultimately unable to repay their loans, depositors may lose some or all of their savings. The challenge is that until depositors know that the loans won’t be repaid, they don’t know that it’s time to withdraw their savings. By that time, it’s too late. We saw this happen in Cyprus several years ago, and it has happened many times over throughout the world. In fact, it happened in Australia in 1893 and 1931. Believe it or not, we nearly had a bank run here in 2008.

Our banking system today is of course electronic. When a bank lends to a consumer, rather than handing over bags of cash, it simply processes a credit into the borrower’s account. This digitalisation of the system has enabled banks to ramp up their lending all the more.

Remember that 99 percent that I mentioned that is loaned out? As long as that's considered to be "tier 1 capital" by regulators, or in other words it's considered to be a conservative investment, then that capital can be included in the 1 percent reserve requirement, even if it's not actual cash in a vault.

Here's what that means: if a bank holds $100 million in deposits, it could conceivably offer $1 billion or even $10 billion in loans. This new "money" does not actually exist, except as 1’s and 0’s on a server, and then as assets and liabilities on a bank balance sheet. Fractional reserve banking increases the money supply just like central bank activity, and much of that new money creation is flowing into housing, causing prices to rise exponentially.

How Does Fractional-Reserve Banking Impact Real Estate Values?

The ultimate reason why real estate is so expensive is because of the new money creation through our fractional-reserve banking system. Without it, there would be much less money available for lending. With less money to lend, fewer people would be able to afford homes. Less demand would mean lower prices.

History clearly illustrates this fact.

Several years ago, a Deakin University Masters student named Phillip Soos wrote a research paper on the history of Australian property values. His study went back 150 years by comparing house prices and land values to a number of fundamental metrics. The following are just a few of his many findings.

This first chart shows us that between 1880 and 1960, home prices remained relatively constant. Since that time, the cost of a home has increased by a multiple of five. This data only goes up to 2012, and we know prices have increased significantly since then.

This next chart shows the increase in the median house price to median income ratio dating back to 1960.

What we can see here is that until the 1960’s, median home prices in Australia were less than double the median annual income. In other words, the typical family could live on 75 percent of its income and use the remaining 25 percent to pay off a home in full within eight years or so.

Today, the national median house price to income ratio is over five to one. Melbourne is about 10 to one and Sydney is about 12 to one. The same family today in Sydney allocating 25 percent of their income to mortgage reduction would take not eight years, but 48 years to pay off their home.

That’s insane.

So, what happened in the 1960’s that caused home prices to start moving up? If we can answer that question, we’ll know the ultimate reason why real estate has become so expensive today.

Until the mid-1960’s, the Australian financial system was much more highly regulated. Banks were required to hold more cash in relation to lending and there were tight requirements on who could qualify to borrow. In short, it was much harder to get a loan back then.

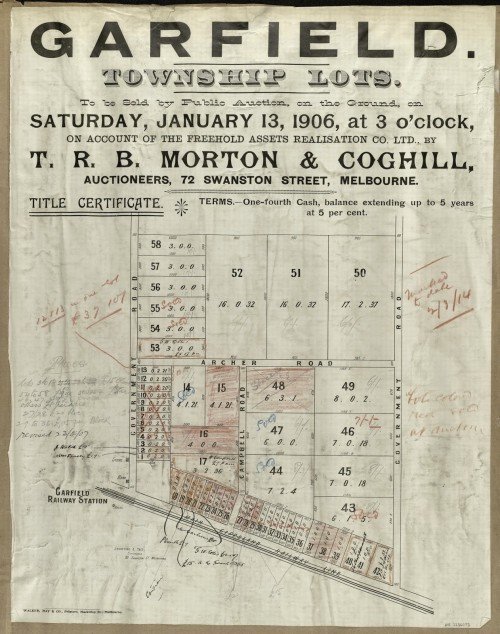

As a result of these tight regulations, banks only loaned money to build houses, not buy land. The land had to be paid for either in cash or purchased from the developer through vendor finance. Here’s an image from a Melbourne developer back in 1906 offering blocks of land on vendor terms.

Pay one-fourth in cash, then pay the balance off over five years at 5 percent.

This inability to borrow required a much different mindset than today, one that promoted savings rather than debt. The number of people who were able to buy houses was therefore limited.

Then the Commonwealth Government changed its regulations, opening the door for banks to more readily lend for housing. Once banks started lending money to also buy land, then savings wasn’t as crucial to home ownership. This meant that many new buyers could enter the market, increasing demand, and property values began to rise.

But even then, it was not like today. Throughout the 1970’s and the early 1980’s, before a borrower could qualify for a mortgage, he would need to show 12 months of savings history and have enough cash to cover a 25 percent deposit. A 75 percent loan-to-value ratio (LVR) was the maximum risk banks could accept. This was due to the government’s tighter reserve requirements back then.

Then in the mid-1980’s, the government, under Treasurer Paul Keating, loosened up even more, further deregulating the financial industry. This opened the door for foreign banks to enter the housing finance market, bringing increased competition and further relaxing lending policies. Banks were able to further reduce the security they required and to lower mortgage interest rates.

You’ll notice by looking again at the first chart from Philip Soos above that the timing of the gradual loosening of the banks’ required reserve ratios perfectly matches the historical increases in the value of real estate. Lower reserve ratios make more money available for lending, thereby increasing the supply of money into the economy in the form of debt. This new money creation has flowed primarily into our housing industry, bringing significant spikes in home prices.

In Summary…

The ultimate reason real estate is so expensive in Australia, and throughout the world, is the fractional-reserve banking system that creates money out of nothing, and central bank policy that has artificially suppressed the costs of borrowing money.

Proximity to a central business district, an influx of skilled migrants, generous tax concessions, and the billions of dollars of foreign investment are only secondary factors driving real estate prices.

If local buyers could not freely borrow, the property market would collapse. It would be impossible for people to pay for homes at today’s prices. If and when lending eventually tightens up, either through government regulation or unstoppable market forces, asset values must decline.

Great breakdown, sharing this one on Facebook for all the negative gearheads out there.

I remember before I left Melbourne, I saw a one storey townhouse in Fitzroy North go for around $700,000... we thought that was excessive. $5 MM for an average block of land is really over the top.

When it finally comes crashing down, I might consider coming back to Aus to see if I can scoop up a bargain. We'll see.

That Kew property buyer was a Chinese guy who wanted his kid in one of the local private schools. A lot of the impulse bidding is people fed up with getting out bid at auctions for the past three months. It may come back to haunt them. If so, cash will be king.

Thanks for sharing the post.

Back in 2008 - 2011 the real estate market and job market here in the United States got brutal. Places like Arizona where I live was hit extra hard. They say there are something like 20% of home owners in Arizona who are still upside down. The prices got cut in half when the crash happened and there would be entire neighborhoods with almost every house being foreclosed on. People would just strategically walk away.

Yeah I was watching all of that unfold from here and then saw the aftermath first hand living back in the States from 2011-2013.

One big difference here is that there is no such thing as a non-recourse loan. The bank will come after you and bankrupt you so people will not be able to just walk away if the housing market corrects or interest rates rise. It could become quite a debacle.

You may find this informative.

Wow, 3.5 hours. Might take me some time to get back to you :)

I quickly scanned through and noticed this is from the mid-90s. It goes to show how long it can take before bubbles burst. We may have a few more years to go here in Australia, as the RBA's cash rate is 1.5%, and can still go a lot lower.

It is fiscally/ physically impossible to pay back interest on money when only the capital exists.

The central bank creates principle out of air and loans it at interest guaranteeing that somebody is going bankrupt because the only way to pay back that interest is to force other loans into default.

A depression resets the books and we are off on the next round of the oligarchs' 'business cycle'.

Sounds like the 2008 US housing crisis all over again.

Our lending standards are higher than in the USA prior to 2008 but our banks are highly leveraged. So if the bond market implodes overseas or the wholesale lending market dries up, a lot of people could be in big trouble.

As always, well researched Jase! I always enjoy reading your articles. Timing is always the challenge. Finding over and undervalued assets can be seemingly easier. No one wants to be that contrarian thinker who arrives two hours before the party starts. The difficulty with real estate is that it can take so long to unwind the asset. By the time you discover the economy has tanked, no one is loaning money and it doesn't matter anyway because no one is buying. Scary times indeed.

Hey Matt! Great to see you on here!

Yeah very true. What do you think of all these Aussie first home buyers taking out interest only loans? This is the first signs I've seen that the banks may be writing some subprime loans.

I spoke to my mortgage broker last week about this. He said the regulations are still extremely strict despite the marketing that is out there. Having an adequate deposit, undervaluing an asset, insisting on having a guarantor or paying higher interest rates are their methods for ensuring security. I understand he is biased and that being upbeat about the Aussie market is his bread and butter. Part of me wonders whether the big banks of the world are idiots who can't manage money or evil geniuses who stand to benefit when the it all collapses. I think they are double dipping and are completely protected for either side of the market.